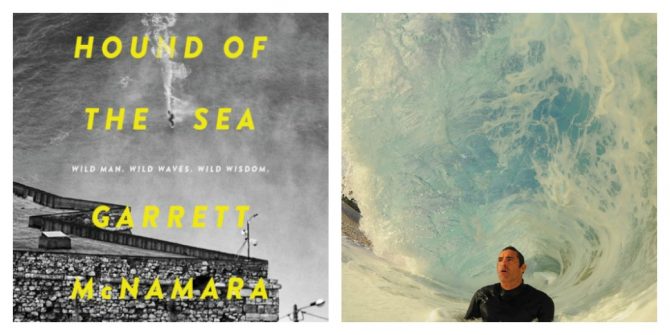

The Gmac memoir you didn’t know you needed is pretty darn interesting. | Photo: Harper Wave

You don’t become a world-class surfer known for charging circa-100-foot swells and discovering a big wave spot without living a remarkable life. What’s surprising about Garrett McNamara’s life is — well, what isn’t? That much becomes apparent quickly upon cracking Gmac’s new memoir, “Hound of The Sea: Wild Man. Wild Waves. Wild Wisdom,” which was released on Nov. 15.

To wit: The guy was raised partly on a hippie commune in Sonoma County where he took his first hit of weed at age 4. His mother, a hippie-turned-devout-Christian, made him and his brother Liam renounce their possessions. As boys, they walked barefoot 25 miles a day, carrying their bedrolls and sleeping under freeway overpasses. (Page 52; we ain’t making this up!)

Not your typical birth into a surf family on the beach.

And consider this. Everything you know about the 49-year-old Gmac is from his life after the age of 35. He broke his back as a 22-year-old fledgling Waimea surfer, all but dashing his hopes of a standard surf career. Amazingly, 13 years later he became the Cortes Bank-charging, 100-foot-swell-riding, Nazare-discovering hellman he is today.

And yeah, he talks about the many controversies that have followed his second act in big wave surfing:

Such as his brother Liam, the “most disliked figure” in surfing:

“Liam has been here month in, month out, waiting. Pipeline and Rocky Point, the breaks he surfed religiously, the breaks he was working in an effort to have a solid career, were and are the most photographed breaks in the world. And, as a result, the most crowded.

This is where the challenges began for him. He was not about to step aside so that some pro who’d just stepped off the plane in Honolulu three hours earlier could take a good wave. Especially in contests, when all eyes were on him, he would go for it.

Writers writing their stories in the surf mags didn’t help matters. Neither Liam nor I were sponsored by the magazines’ big corporate advertisers. We didn’t ride for Billabong, for example, so we were easy scapegoats. Stories need a villain, and Liam was as good as any, especially because he was unrepentant. Why shouldn’t he be? There were California surfers who were blond and laid-back, and there were Aussie surfers who were radical and hard-charging, and there were noble and revered Hawaiians who could be as gnarly as they pleased because the entire world was encroaching on their perfect and unique waves, and there were eccentric South Africans and a few mysterious Tahitians, and there were drugs and there were feuds and choke outs and all the drama of any insular world, but there were no real bad guys. There were badasses, there were bad boys, but no bad guys. Except for Liam McNamara.

It was unfair. For refusing to play by the very specific rules of the lineup, he was offered up in the service of controversy and drama. He sometimes complained that the judges of the contests were prejudiced against him, and who’s to say they weren’t? His entry in Matt Warshaw’s respected Encyclopedia of Surfing says he’s “often mentioned as the sport’s most disliked figure.” I lived under his shadow, the brother of Liam. People who didn’t know me disliked me. Even though I tried to stay out of the lineup when Liam was there, I felt the chill whenever I paddled out.”

And his alleged drop-in on Greg Long at Cortes Bank:

“Two days later Greg issued an eloquent statement to the press explaining what happened and thanking everyone who saved him. He acknowledged the high level of risk involved in surfing big waves, and at Cortes Bank in particular. He never mentioned my name, but he didn’t have to. The surfing press was already buzzing, accusing me of dropping in—the most heinous crime in surfing—and further raking me over the coals for using the WaveJet, an invention I’ll always defend because it gives folks who might otherwise never have the opportunity a chance to experience the exhilaration and pure joy of riding a wave. Some surfers just need a little extra speed, but there are also people like Jesse Billauer, a California surfer who became a quadriplegic at seventeen when he broke his neck during a wipeout, who’ve been able to surf again unassisted using WaveJet technology. It’s also been adopted with enthusiasm by lifeguards, since the WaveJet allows them to reach drowning swimmers faster.

Surfing purists, who would have us all surfing on planks of wood and wearing loincloths, despise pretty much all technological advances in the sport, and wanted my head. During interviews surf journalists, who are supposed to be impartial, prefaced questions with stuff like, “Garrett McNamara . . . essentially cut him off. And on top of that Garrett McNamara was riding a WaveJet. Those things repulse me. I am not a big fan of WaveJet at all. I don’t think they belong in the lineup. That’s just me. What’s your take on it?”

The comment sections of every surf news report and blog post of the incident bristled with stories of what a monster I was, of how I’d dropped in on them in two-foot waves fifteen years ago at a place I’d never been to and practically killed them. If I’d dropped in on all the people who said I’d dropped in on them, I would have been banished from the sport long ago.

Even though Greg kept reminding the world that big-wave surfing, especially at a place like Cortes Bank, is a high-risk activity and what happened to him was not unexpected and that he’d trained for such a thing for years, someone needed to take the heat. Someone needed to be blamed.

I issued my own statement telling my side of the story and apologizing for any part I may have played. It fell on deaf ears. Three weeks later, in early January 2013, Greg issued another statement saying that I wasn’t to blame. That only served to make him seem more gracious, to whiten his hat and blacken mine.”

And what might be the biggest wave ever ridden:

“The picture is amazing. The angle makes it look bigger than it is and from a purely photographic perspective the Nazaré wave has an advantage that no other monster wave possesses—it can be compared to something other than the little surfer at the bottom of it. The viewer sees the lighthouse perched high on a cliff and thinks, What is that, eighty feet up? And the wave looks even taller. It requires no leap of the imagination. It’s something everyone can relate to. The viewer thinks, That could be me standing on the roof of that lighthouse. Holy shit!

The picture went viral. The media kept pumping it up as the hundred-foot wave no matter how much I said that it was an intense swell to ride but I’m not sure it was even a wave, technically, and I have no idea how big it was anyway. Really, no one cared what I said.

Predictably, the surfing world lost its mind over my “claiming,” even though anyone who cared to click around a bit for ten minutes would see I had nothing to do with it. Likewise, bitter, would-be surfers who sit in an office all day more or less dismissed Nazaré as having any kind of viable waves, much less a world-class giant. In fairness, some of the good guys stepped up and acknowledged that I’d achieved something most surfers dream about—discovering and pioneering a new wave and making a career out of surfing. South African big-wave charger Grant “Twiggy” Baker, 2014’s Big Wave World Tour champion and a regular at the XXL Big Wave Awards, admitted that what I’d accomplished was “every man’s dream.” But there was also the usual bad press. I was used to it by now. All that daily practice of acceptance.”

Gmac’s book was written with author Karen Karbo, known for penning books on famous women including Julia Child, Georgia O’Keeffe and Coco Chanel. Whether from Karbo’s touch or Gmac himself, the prose is visceral, clean and quick-moving. If you’re under 34 and have yet to make your mark on the world, “Hound of The Sea” might offer some relief. If not, it’s still worth a look.