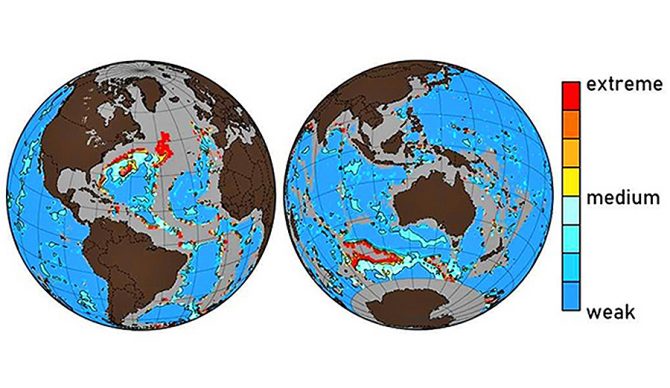

A map showing the areas in which the ocean floor is most affected by acidification. Photo: McGill

“Oh boy, another scary climate change doomsday headline…” It’s repetitive and constant enough that we can almost let the day’s newest dire news about the ocean drown itself out. Earlier this week the latest revelation was that the oceans are actually warming faster than we’d originally thought. Today its, well…you already read the headline.

Ocean acidification is probably a term you’ve heard before. It’s a process of decreasing pH caused by a rise of CO2 in the atmosphere. Most of this is seen and noticed near the ocean’s surface, which is why we hear so much about it affecting coral reefs and the marine life dependent on them. Findings from a new study by the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) suggest the problem is actually a lot deeper. Literally.

The ocean floor is lined with calcium carbonate, which is made of shells of zooplankton that have died and sunk to the ocean floor. When carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is absorbed into the ocean, the water becomes more acidic but the calcium carbonate neutralizes that carbon and produces bicarbonate. It’s a nifty little cycle the ocean has relied on to absorb excess carbons and regulate its pH. Only now, it turns out there’s so much carbon dioxide being absorbed into the ocean that all that useful calcium carbonate is dissolving too fast to keep up. According to PNAS’s study, parts of the seafloor are actually disintegrating because of it, with the layer of the ocean that does not have any calcium carbonate having risen more than 980 feet in some areas.

“Because it takes decades or even centuries for CO2 to drop down to the bottom of the ocean, almost all the CO2 created through human activity is still at the surface,” says lead author Olivier Sulpis who is working on his Ph.D. in the earth and planetary sciences department at McGill University. “But in the future, it will invade the deep-ocean, spread above the ocean floor, and cause even more calcite particles at the seafloor to dissolve. The rate at which CO2 is currently being emitted into the atmosphere is exceptionally high in Earth’s history, faster than at any period since at least the extinction of the dinosaurs. And at a much faster rate than the natural mechanisms in the ocean can deal with, so it raises worries about the levels of ocean acidification in the future.”

Researchers conducted their study by building seafloor-like microenvironments in a laboratory where they reproduced abyssal bottom currents, seawater temperature and chemistry, and sediment compositions. By controlling variables in each environment, they were able to understand what dictates dissolution of calcite in marine sediments and ultimately compare pre-industrial and modern seafloor dissolution rates. For the most part, they found that the pre-industrial and modern dissolution rates were actually not that different with the exception of what they called a few “hotspots.”

“We determine that significant anthropogenic dissolution now occurs in the western North Atlantic, amounting to 40–100 percent of the total seafloor dissolution at its most intense locations,” the report reads. “At these locations, the calcite compensation depth has risen ∼300 m. Increased benthic dissolution was also revealed at various hot spots in the southern extent of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans.”

“Just as climate change isn’t just about polar bears, ocean acidification isn’t just about coral reefs,” says David Trossman, a research associate at the University of Texas-Austin. “Our study shows that the effects of human activities have become evident all the way down to the seafloor in many regions, and the resulting increased acidification in these regions may impact our ability to understand Earth’s climate history.”