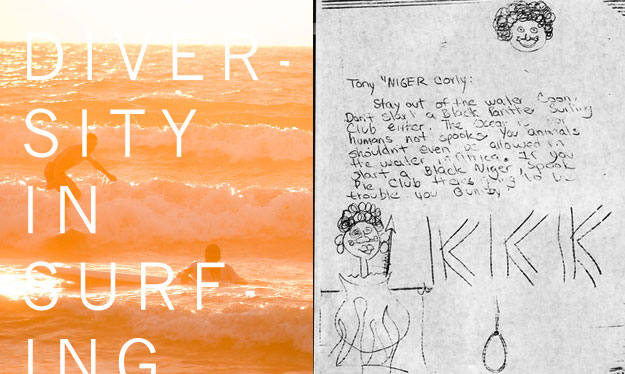

Palestinian and Israeli surfers find common ground in the lineup through a documentary by Alex Klein. A piece of hate mail delivered to Black Surfing Association president Tony Corley. Images: Klein (L), Corley (R)

On December 12, 2009 on the North Shore of Oahu just a few hours after Mick Fanning cemented his second ASP World Title, Stab Magazine writer Chas Smith and the newly-crowned two-time World Champion shared an awkward and unpleasant exchange that resulted in Fanning calling Smith a “f—cking Jew” several times before Smith was escorted from Rip Curl’s beachside estate. While that exchange could have been filed into a bin full of awkward, unpleasant interactions in the history of testosterone-driven clashes on the North Shore, it went a much different route. It went to print. And that event, from its debated retelling to its controversial reception by purveyors and consumers of media inspired me to investigate bigotry in surfing more broadly. It needed to be done, if only because it hadn’t.

While surfing (like most sports) can be a transcendent unifier, it has also developed an astoundingly ironic and nuanced culture. We sell ourselves as inclusionists at every opportunity, yet we often conveniently forget to acknowledge that much of our world revolves around status signifiers, intricate hierarchies, and flat-out exclusivity. To a large extent, surf culture thrives on divisiveness. Haole. Kook. Grom. Seppo. Locals Only. Longboarders. SUPers, etc… In the surf world, Hawaiians aren’t considered Americans. And most Hawaiians like it that way; Surfing can be a parallel universe, and at times, we’ve excused some overtly bigoted behavior regarding race, religion, and sexuality. As a result, I think it’s in surf culture’s best interest to take a closer look at the blemishes we’re all too eager to Photoshop from the frame. Maybe then we’ll actually embrace the ideals we espouse, and I’m confident that surfing’s image – even with a smudge – will be just as inspiring.

***

Mick Fanning competing at Pipeline in 2010. In 2009, his runner-up finish cemented his 2nd ASP World Title. Photo: ASP/Kirstin

“It was part of a broader story that was just a snapshot of the North Shore,” said Chas Smith, whose article entitled Tales of a F—king Jew appeared in Stab’s January/February 2010 issue. “My whole intent in the way I wanted to cover it was just day-to-day snapshots of what it felt like – from the company houses to the feeling on the beach to the competitions to every part of it, and since that was something that happened…it became part of the story.”

It became much more than just “part of the story.” It became the story – attracting global attention when Fanning’s lawyers pressured Stab to remove the issue from newsstands. Fanning declined further comment, but offered a public apology for using anti-Semitic language in a formal statement on his web site shortly thereafter.

Fanning also apologized to the NSW Jewish Board of Deputies and went on to condemn Stab’s tendency to publish inflammatory editorial. “Prior to the exchange with the reporter, I had refused to speak with him because I understood he worked for Stab Magazine and that it had previously published articles which I believed were racist and anti-Semitic,” said Fanning. “I strongly object to views, statements and comments of that nature.”

Fanning, whom I’ve interviewed at length several times but otherwise know very superficially, has always carried himself respectfully and diplomatically in our exchanges. He also has a strong record of public service in minority communities.

“Mick’s thing was a big mess,” ten-time World Champion Kelly Slater wrote me via email in September. “We’re still talking about it now. If the true situations are understood they don’t turn into this. Stab likes to get ‘inside’ info then sensationalize it for their own gain, so there were a lot of seemingly innocent people in that situation pointing fingers at Mick but creating the situation in the first place.”

Slater and Fanning make a salient point in identifying Stab’s record of publishing anti-Semitic and/or racist language. In 2008, Stab published a Fascist themed Issue that was guest edited by Chas Smith, which began with a passage from Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf and the following introduction, in the words of Mr. Smith:

“Maybe I slather a surf magazine with Goring, Himmler, Eichmann, Hess, Jodl, and Raeder because I can…That might make me a lazy/sadistic asshole, using simple imagery loaded with negative meaning in order to make a pointlessly shocking impression. You might be very angry with me when, at the news agency, you see an old Auschwitz surviving grandma weeping uncontrollably at the symbol of her people’s destruction plastered on a surf magazine….OR it might make me the super funnest person on Earth! Swastikas? Yaaay! Hate-filled ranting? Yaaaay! Totally fabulous uniforms? Yaaay!” – Chas Smith, Stab Magazine Guest Editor

Smith (who is a Calvinist Christian) told me (Jewish) that he feels justified in publishing editorial of this variety without much respect for its context so long as it provokes dialog. “From my perspective, I totally understand that all of these things are dangerous areas, but if nobody talks about them, or everybody talks about them in the same way, then I don’t know how a dialog can happen,” Smith told me in a phone interview shortly after his article was published. “If I’m going to be around and editing myself always I don’t see what the point of writing is. I think that being an edgy publication there’s always danger. You never know where the edge is until you fall over it.”

“There was a surf shop in Florida that used to put big swastikas on their boards, and I got hold of them and I really raised hell with them,” said Dorian “Doc” Paskowitz. “They called the Klu Klux Klan guys in, and that really scared the shit out of me.” Photo: Art Brewer

Stab provoked a similar backlash in February of 2010 when writer Jed Smith published an article online entitled Super Breed Descends. In the article, Smith referred to Jamaican surfer Icah Wilmot as “a negro” several times and sarcastically announced the impending fall of white surfers.

“Last week this multi-talented Negro became the first Jamaican winner of the Pan American championships, held in Cuba, signaling, amongst other things, an uncertain future for the Aryan domination of surfing,” wrote Smith. The ensuing outrage prompted the publication to delete the article from the website and the author to write a formal apology to the Wilmot family. It appeared that the writer intended no harm; he hoped to make a point ironically, but the damage had been done.

A few weeks later I caught up with Icah Wilmot to hear his perspective.

“Ever since the sport hit the mainstream market, the image of a white guy surfing on a blue wave has been the image of the sport,” said Wilmot. “The surfing industry needs to realize that the new nations and races in the sport with the correct amounts of support and exposure will bring surfing to the international arena. This increase in diversity of nations, and religions, and surfers within the sport is the only way forward for surfing in my point of view.”

****

To provide a bit of context, Stab’s Fascist issue was not the first time that surf culture has associated itself with the official emblem of the Nazi party. In fact, the swastika itself post-dates Nazi Germany, and was used by Eastern religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism as a symbol of peace and prosperity. With that in mind, an early surfboard manufacturer known as Pacific System Homes Surfboards built high-quality multi-wood surfboards that featured swastikas burned into the tail. According to Matt Warshaw, author of The Encyclopedia of Surfing and The History of Surfing, it was common for affluent surfers to own Swastika surfboards. Later, when the Nazi party made the swastika its official symbol, PSHS renamed the line Waikiki Surfboards and altered their logo.

While PSHS distanced itself from the swastika when its connotation soured, many surfers continued to adopt it as a symbol of rebellion. According to Warshaw’s The History of Surfing, “In the 1959 film Search for Surf, three La Jolla locals dressed in Nazi stormtrooper uniforms…marched across the sand with blank-loaded automatic weapons, and ‘shot’ anyone wearing a bathing suit. Then they lowered themselves into a storm drain with a pair of Flexi-Flyers and sledded down to a beach outfall, where friends were standing by cheering and waving a Third Reich flag.”

Said Greg Noll in The History of Surfing, “We’d paint a swastika on something for no other reason than to piss people off. Which it did. So next time we’d paint two swastikas, just to piss ‘em off more.”

Through the 1960s and beyond, surfers effectively co-opted swastikas and Iron Crosses as symbols of suburban rebellion, sometimes referring to themselves as “surf Nazis.” “It meant that you were hardcore,” Warshaw told me over the phone. “People who were throwing those phrases around may not have even have known what it meant. It was the equivalent of being a frother, you know?”

More recently, professional surfers like Christian Fletcher have used equipment with swastikas and Iron Crosses boldly imprinted upon them, and although many presume that the iconography represents innocuous suburban rebellion, Jewish surfers can attest to the attitude’s more harmful affects.

“The early Orange County surfers were really anti-Semitic,” says Dorian “Doc” Paskowitz, the Paskowitz family’s 91-year-old patriarch. “I used to take a big beating for being Jewish in the early days. But I love to surf and I love to be around surfers so much, even though they used to give me a really bad time about being Jewish.”

“One incident that really upset me is that there was a surf shop in Florida that used to put big swastikas on their boards,” said Paskowitz, “and I got hold of them and I really raised hell with them, and they called the Klu Klux Klan guys in, and that really scared the shit out of me.”

According to Warshaw, the KKK’s ritual of burning crosses made a rare migration to Southern California when a group of surfers burned a cross in Kathy Kohner-Zimmerman’s (the inspiration Gidget), yard. Kathy Kohner’s father, Frederick Kohner was a Jewish-German filmmaker who fled Nazi Germany to Southern California and wrote the film about his daughter. One day, a member of the Malibu crew discovered Kohner was Jewish and torched a cross in their Brentwood driveway.*

In 2007 Doc Paskowitz formed Surfing 4 Peace, an organization that “that aims to bridge cultural and political barriers between surfers in the Middle East.” Over the past four years, the group has organized several events and gestures of goodwill in Israel, but Paskowitz says he’s seen little progress in changing attitudes of bigotry within surf culture.

“I think the little gang at Malibu is gone,” says Paskowitz. “They’re not there anymore to fan the flames, but I think the same attitude exists.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the relationship and identity of Kathy Kohner-Zimmerman and Frederick Kohner. The article alleged that Kohner-Zimmerman was the actress who played Gidget and was married to Frederick Kohner. In fact, Kohner-Zimmerman was the inspiration for Gidget, and Frederick Kohner, the movie’s writer, was her father.

“It was for fraternity,” says Black Surfing Association Founder Tony Corley. “That’s kind of why I started the Black Surfing Association.” The BSA at the 2011 Rincon Invitational in March. Photo: Ken Samuels/BlackSurfingAssociation.blogspot.com

By contrast, Shaun Tomson, a Jewish surfer and former World Champion who grew up in South Africa during the peak of apartheid feels that surf culture isn’t particularly unkind to any group, but struggles the same way most cultures do when addressing complex issues.

“I don’t think surfing is a discriminatory culture,” says Shaun Tomson. “I think there are elements of racism in the surfing culture. I mean, calling someone an ‘f-ing Jew’ is as bad as being called an ‘f-ing haole’ or being told to get off a particular beach because you don’t live there. I don’t think that surfing is deliberately a discriminatory sport as in it’s a white man’s sport. You go to Hawaii and there are more Polynesians surfing than there are Caucasians; that’s where our sport came from. It’s the spiritual birthplace, and the roots of our sport are not in the Caucasian culture but in the Polynesian culture.“

“I’ve seen the effects of racism,” continues Tomson, who along with his dad, provided Eddie Aikau a place to stay after Aikau was refused service at a South African hotel in 1972 because of his skin color. “I think I’ve been the victim in some ways of it, but the way to snuff it out is to bring it out in the open – not sweep it under the rug and try to ignore it. I think just generally surfers need to be more compassionate and more considerate about other people, other surfers, and other population groups. In the last three or four years there has been a general breakdown in the way surfers treat one another in the lineup. I mean, it’s war out there; I surf Rincon all the time and I think it’s indicative of the lack of passion that one surfer feels toward another and I think an issue like [Fanning’s comment] can help us reevaluate how we treat other people.”

***

In January of 1974, Tony Corley, an African-American surfer from San Luis Obispo, wrote a letter that was published in SURFER Magazine to reach out to other black surfers. He had only met a few since he started surfing in 1963, and a few months later he began to receive responses. The second letter Corley received (as dictated by Corley) read:

A hate letter to Black Surfing Association president Tony Corley.

Tony “Niger” Corley, (‘He spelled the word nigger wrong,’ notes Corley.)

“Stay out of the water, coon. Don’t start a Black Panther Surfing Club either. The ocean is for humans not spooks. You animals shouldn’t even be allowed in the water in Africa. If you start a black nigger, spook pie club coon surf club, there’s going to be trouble for you, gumby.

At the bottom of the note were the letters K-K-K, a picture of a hangman’s noose, and a sketch of an African man burning in a pot of flames.

Soon after receiving that letter, Corley founded the Black Surfing Association. “It was for fraternity,” says Corley. “There were other white surfers around and they befriended me and I befriended them too, but after the surf session when we’re hanging around and always somebody would say something about a nigger or a nigger joke or some kind of shit like that, and it’s like, ‘God dang it…you know?’ What should I do? Should I fight or flight? Do I want to go up and sock him in the head and have three or four guys jump on me or do I just want to leave it alone? In a way, that’s kind of why I started the Black Surfing Association.”

Corley, now 61, has maintained the organization and its hundreds of members to this day, effectively becoming a patriarch to the black surfing community.

“All my acquaintances and members have a racist story to tell about being in the water or outside of the water as well,” says Corley, “but Mother Ocean knows no prejudices at all. She’ll slap the shit out of you or make love to you and bring you back again. She’s a wonderful woman.”

Ted Woods, a young filmmaker based in Los Angeles, decided to examine the intersection of African-American culture and surf culture in his 2009 documentary, Whitewash. What he found, was a community with very little representation and a surprisingly inert social structure. After all, most U.S. beaches (like Santa Monica’s “Ink Well” ) were fully segregated or reserved exclusively for whites until Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka deemed segregation unconstitutional and catalyzed the Civil Rights Movement in 1954. Even then, old habits die(d) hard.

“Mother Ocean knows no prejudices at all,” says Tony Corley, founder of the Black Surfing Association. “She’ll slap the shit out of you or make love to you and bring you back again. She’s a wonderful woman.” Corley (L) pictured with fellow BSA Member Gregory Rachal at the annual BSA surf retreat in 2008. Photo: Courtesy Tony Corley

“I think overall, what it really comes down to is there isn’t an overwhelmingly welcome feeling [towards black surfers],” says Woods. “Most of the black surfers we talked to had experienced bigotry, racism, or whatever whether outright – some of the older guys had fights and death threats and some of the younger guys have had more thinly veiled comments made. The surf community has made very little effort – the surf media and media in general have made absolutely no attempt to bridge that gap. I don’t think they necessarily see a need to. I think that’s fine within the surf community, because it protects what they want to protect.”

Woods isn’t alone in his attempt to bring such tensions to light. Alex Klein, a 29-year-old filmmaker based out of New York City, staged a similar conversation by focusing on surfing’s ability to bring peace to Israeli and Palestinian surfers in his film, God Went Surfing with the Devil.

“The way I view it – the conflicts are generational, and with every new generation there is a chance to make progress towards peace,” said Klein, a University of California Berkeley graduate and former professional skateboarder. “It’s really through the power of surfing that [the Israeli and Palestinian communities] were able to transcend the violence. The Palestinians say when they paddle out they feel free. To me, it was incredible to see how they could utilize surfing to put this violence and strife behind them. Obviously, you can’t teach everyone in the world to surf, but that attitude I think can spread throughout the rest of culture and society. It will take time, but I’m hopeful.”

Klein’s optimism matches the inclusive buoyancy intrinsic to the sport of surfing itself.

Tony Corley notes, “Surfing is such an equalizer. You can go out and have the best time of your life or you can die. Mother Ocean knows no bounds.” She is vast and unforgiving, and although surf culture is susceptible to the same misunderstandings that inspire fear and hatred around our planet, I am convinced that open, respectful dialog coupled with a transcendent interaction with nature is a powerful antidote. If Jews and Palestinians can set aside their religious and political differences long enough to share the same lineup and the same exhilaration caused by the simple act of riding wave, then maybe we can set an example for the rest of the world to follow. We can trailblaze. Move forward.

The ocean won’t mind.

“In the sport of surfing, one thing sticks out in my mind above everything else,” says Doc Paskowitz. “There is one character of surfing that trumps all others, and it is the almost otherworldly, supernatural, cosmic effect of surfing – of riding a wave – of paddling out, seeing a wave, turning around, paddling, catching a wave, standing up and riding it in. There is a kind of result to that behavior which is so passionate, so positive, so fulfilling, so soulful – that at that instant there is a spiritual dynamic. A kind of an extraordinary feeling that ordinary guys get that is so overpowering that it raises you above anything that is negative and contrary to the sweetness of life.”