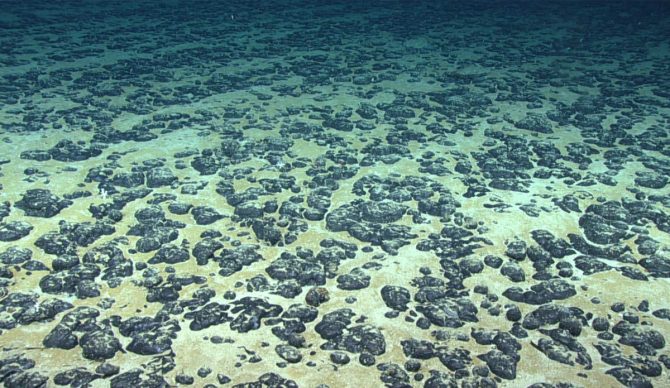

Polymetallic nodules on the ocean floor. Photo: NOAA

Deep-sea mining could pose a threat to whales, dolphins, and other sea life, according to new research. In light of increased interest in deep-sea mining, two new scientific surveys have raised concerns over the possible effects it could have on marine wildlife.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) is an abyssal plain covering 1.7-million square miles between Hawaii and Mexico. Lying on that sea floor are trillions of polymetallic nodules, potato-sized deposits containing nickel, manganese, copper, zinc, cobalt, and other minerals. Though many scientists have warned of the potential negative impact of disturbing this seabed, the region has become a target for mining operations. The International Seabed Authority (ISA), which regulates mining in the international seabed, has awarded over two dozen exploration contracts to state sponsors and contractors allowing them to assess mining opportunities within the CCZ.

The first survey, published today in the scientific journal Frontiers in Marine Science, studied two regions in the Clarion-Clipperton zone targeted by Canadian firm The Metals Company (TMC). Researchers from the University of Exeter and Greenpeace Research Laboratories confirmed the presence of whales and dolphins, including sperm whales, which are listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

“We already knew that the Clarion-Clipperton Zone is home to at least 20 species of cetaceans, but we’ve now demonstrated their presence in two areas specifically earmarked for deep sea mining by The Metals Company,” Lead Study Author Dr. Kirsten Young told Greenpeace.

The second paper, published in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin, concerned the possible effects of noise from deep-sea mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Up until now, research has been focused on the effects of habitat destruction and plumes of sediment created by mining vehicles, but the effect of continuous noise pollution from mining activities has been less closely studied. Many marine animals rely on sound for communication, navigation, and predator avoidance, and we still do not know the full extent of the impact mining would have on them.

“We know remarkably little about these ecosystems, which are hundreds of miles offshore and include very deep waters,” Young told Oceanographic Magazine. “We do know many species here are long-lived and slow-growing, especially on the seabed. It’s very hard to predict how seabed mining might affect these species and wider ecosystems, and these risks must be urgently assessed.”