A year ago, who would’ve thought we’d be flying around with these mini glider kites? Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

The latest revolution in wind and foil sports is in full effect with the explosive emergence of parawinging. Even a year ago, it would have been hard to imagine that today we’d be zipping around on foil with nothing but a tiny, collapsible kite in our hands. But looking back, it’s easy to see the progression that led us here.

Better foils, providing incredible glide without compromising fun and user-friendliness. Midlength boards, providing the easy foil starts necessary to get up and going with something like a parawing while remaining nimble and playful. Even the Foil Drive could be seen as a precursor to the parawing, as we searched for new and interesting ways to get closer to that experience of hands-free foiling. If there is anything to be learned from the world of windsports, and the rapid progression of these wind and water-driven activities, it’s this: Just when you think the industry has reached a plateau, is when the next perspective-shifting invention is on the horizon.

At this point, we’re all at least parawing-curious, and more than a few riders have already made the switch entirely. It’s a bit of a strange twist that, in a way, parawings were invented to be used as little as possible – that is, to be used to get up on foil and then put away while riding downwind. However, following the first BRM Maliko parawing in the late summer of 2024, we’ve seen rapid adoption and more than a dozen parawing models coming to market, and many riders are already using them for free riding. It’s clear that while parawings have opened up downwinding to a ton of new riders, many people are going to use parawings as replacements for inflatable wings, whether or not that’s what they were originally intended for.

Parawings offer some unique advantages over inflatable wings. Although this photo may suggest otherwise, fewer crashes is not one of them. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Parawings offer several advantages over inflatable wings, with their packability, lighter weight, simplicity, and the lack of the need for a pump. That said, most parawings still have a narrower usable wind range than inflatable wings, and many people find that parawinging requires a higher degree of athleticism.

Parawing gear is in rapid development at this early stage, and most of the brands that we cover here are already working on updates. Also, keep in mind that our testing was done in San Francisco Bay, and our conditions here always require a lot of upwind riding. We don’t really have the conditions for mega downwinders, but we certainly put these wings to the test in high wind, swell, big bay chop, ship wakes, and ultra-powered upwinding, reaching, and hot laps of all sorts.

Much respect to the designers and manufacturers who have put in the work to develop and bring these new parawings to market. All of the products included here are well-built, but there are important differences. Our goal here is to provide our best and most authentic, direct, and usable feedback on parawings currently available for various uses.

In this comprehensive article, you’ll find an industry-first comparative review covering the first full season of parawing product releases, with awards for the best wings by category and a side-by-side comparison table, along with a rundown on parawing disciplines, a discussion on parawings versus inflatable wings, as well as a complete buyer’s guide to parawing technology and design features.

Navigate To: Comparison Table | How We Tested | Buyer’s Guide

Related: Best Foils | Best Wingfoil Boards | More Foil Reviews

The F-One Frigate wins top marks in more categories than any other. Photo: Ed Sileo//The Inertia

The Best Parawings

Best All-Around Parawing: F-One Frigate

Most Nimble and Packable Parawing: BRM Kanaha

The “Pop-Out” Freeride Machine: Flysurfer POW

The Rock-Rolid Ripper: Ozone Pocket Rocket

A Solid All-Rounder: Flow D-Wing

Best “Budget” Parawing: Aeryn P1

An Interesting Parawing Alternative: F-One Plume K-Wing

“Ground handling” practice at Crissy Field. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Best All-Around Parawing

F-One Frigate

Sizes: 2.5 / 3 / 3.5 / 4.0 / 4.7

Size Tested: 3.5m

Price (4m): $1,049 (includes harness line)

Best For: All-around, upwind, free riding, riding swells, upwind/downwind

Defining Characteristics: “Dynamic bridle system,” stash handle, waterproof canopy material, included harness line

Pros: Best upwind performance, very wide wind range, very stable, excellent refly, great bar, outstanding lineset and color coding, includes harness line

Cons: Lines are a bit longer than we’d like

A global brand with a full suite of wings, kites, boards, and foils, F-One announced their Plume K-Wing in early 2025 and the Frigate in June 2025. We’ve flown a lot of parawings in the last few months, and although there are now several excellent choices on the market, the Frigate wins top marks in more categories than any other.

The Frigate really makes its mark with its very broad usable wind range, going from the low end where you can really pump the wing thanks to an internal structure with cross-bracing, through a wide sweet spot of user-friendly power, to an extensive top end. While at first we didn’t expect parawings to go upwind as well as wings, nor to have the same breadth of wind range, with the Frigate, we’re getting a parawing that gets extremely close to the performance and versatility of inflatable wings. Not only that, but the Frigate is fast – we easily hit the same 20-25 mph top speed that we do when winging, without any struggle.

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

The Frigate is also very stable when highly powered. No collapsing, squirming, or yapping. On a day when a 2.5m wing was a better match to the wind range, we did finally get the 3.5m Frigate to complain a bit, but that shows – fair enough – that there is a point where any sail gets legitimately overpowered. In normal usage, and well up into the heavily-powered range, the Frigate feels very user-friendly. This versatility is thanks in part to what F-One calls their Dynamic Bridle System, which activates “certain bridles when the sail is sheeted out and others when it is sheeted in,” without the use of a pulley. One small bug is that when overpowered and flying off the extreme front end of the bar, the front lines can pinch your hand — a good signal, however, that you are indeed overpowered, and should switch down a size.

The mid-aspect, rounded shape of the wing also makes for intuitive trimming, excellent agility, and easy relaunch. We also give credit to F-One for building the Frigate bar at what we’d consider to be just the right length — being 33cm / 13in, the compact bar packs away really well, and it’s still wide enough to give plenty of grip and control. Furthermore, unlike almost all the other brands, F-One includes a harness line! This small but thoughtful and highly functional touch means not only that you can ride the Frigate right out of the bag, but you benefit from the designer’s thought process right down to the harness connection, which we find critical for riding upwind. We love the single-point harness connection. Although some riders may prefer a stretchy harness line, the benefit of the semi-rigid F-One harness line is that you can easily hook in one-handed.

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

The Frigate’s lineset is top-tier, with great line feel and color coding everywhere. The lines are shorter than the POW and the Ozone, but a bit longer than those of the Kanaha. Surprisingly, we found that the collapse wasn’t quite as clean as with the POW or the Ozone, which both rosette more cleanly, or the Kanaha, which wins the stash game with its minimal structure and short lines. Still, the Frigate has good collapse, stash, and packability, and a reliable, quick relaunch. Note that here, we’re not discussing line length, but how cleanly the canopy collapses as you “stroke” the wing, or run your hand up the A lines to collapse it. And once we switched to grabbing just the four middle A lines of the Frigate, the collapse and rosette got much cleaner.

Overall, the top-flight performance of the Frigate reflects F-One’s deep history in kite and wing design, including the legendary Bandit kites and their killer Diablo parafoil race kites. Kudos to the entire F-One team and Frigate designer Nicolas Caillou!

check price on MacKite

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Most Nimble and Packable Parawing

BRM Kanaha

Sizes: 2.5 / 3.2 / 4.0 / 4.7 / 5.5 / 6.2

Sizes Tested: 2.5, 3.2 & 4m

Price (4.0m): $1,000

Defining Characteristics: Great line set, compact bar, yoke that bridges A and C bridles

Pros: Light, most packable, clean re-deploy, elegant, nimble, goes upwind very well, excellent range

Cons: Less low-end than the Frigate and the POW, not quite as fast in an upwind race, some people may not love the short bar

After pioneering the category with the first upwind-capable Maliko parawing in 2024, BRM was again first to market with second-generation parawings in early 2025. BRM offers three models: the Maliko 2 for downwinding, the Kanaha with max upwind ability and stability, and the Ka’a, with the shortest lines and maximum responsiveness for quick collapse-and-refly riding. The Kanaha has a higher aspect ratio than the other two BRM models, but has a lower aspect ratio than the Ozone Pocket Rocket, and is widely regarded as the most versatile BRM v2 parawing. This is the model we did most of our testing with.

We found the Kanaha to be an excellent tool that benefits from BRM’s history with the pioneering Maliko V1, as well as the brand’s unique Cloud kites. The BRM parawings feel like the result of an organic, evolutionary process, resulting in a parawing that’s remarkably stable, powerful, and highly versatile, with a wide wind range, decent low end, excellent upwind performance, and still flies quietly even when pushed to the point of starting to deform when completely overpowered.

Of all the wings we tested, the Kanaha has the shortest line length and stiff, smooth line material, making the total package very nimble, enjoyable, and reliable to make turns with, and easy to retract, wad, stow, pack, and redeploy – the best, in many ways, for what parawings are designed for. That is: riding on foil alone, with the wing stashed away.

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

On the downside, given the lower AR, the Kanaha doesn’t quite match the top speed or upwind angles of the Ozone, Flysurfer, or F-One parawings. To be clear, the Kanaha goes upwind very well, and it can be made to hit the same top speeds, just not as easily. The resulting combination of speed and upwind angle – known in sailing terms as VMG – is very good, just not quite as good as with the other three leaders. The BRM parawings, in particular, want to fly low when powered, so when you want to grind upwind, bury the wing and the foil and let the wing push through your feet.

As for wind range, the Kanaha hangs with the best of them at the high end, never collapsing or complaining much even when very heavily powered to the point of deforming the leading edge. Performance when overpowered is a highlight feature of the Kanaha, as it remains more stable and well-behaved than almost any other parawing on the market when overpowered. At the low end, however, the lack of structure in the Kanaha means that it’s harder to get as much power out of the wing when pumping as with more structured wings like the Frigate and the POW.

All BRM parawings share the same basic construction, super compact bar, and the “yoke” (sometimes also known as a “mixer”) that bridges the A and C bridles, eliminating the need for a middle bar-bridle connection. In flight, the yoke provides stability and uniquely responsive micro-adjustment of the canopy trim that many riders will appreciate.

BRM bar and bridle yoke. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

The BRM v2 parawings all use the same ultra-compact two-line bar – the shortest on the market – which contributes to the superior packability of the BRM wings. The BRM bar is the only bar that has any space for your hand in front of the front lines, which is a unique feature that riders will appreciate going upwind, and the exposed upwind end of the bar makes it possible to loop the front lines around the end of the bar to get more power in light wind, as shown here.

On the other hand, the short bar may become uncomfortable for some people as they get wound on the larger BRM wings, so much so that, especially in the larger sizes, we feel that a longer bar may increase the usable high-end wind range of the wing for some riders. Fortunately, BRM offers a carbon bar for their original v1 parawings that can be used seamlessly with the v2s as a longer bar, or trimmed to preference, for riders who want that option. BRM also has two different harnesses/belts and two harness line options that match perfectly with their v2 parawings.

We tested the 3.2 and 4.0m Kanaha, which is the wing that Greg says he almost named the “SF,” since it was designed with the type of riding that we do here in mind: blasting upwind to grab a few swells or bumps (or a ship wake), wadding up or stashing for the downwind ride, and then jamming upwind again. We didn’t test the Maliko 2 or the Ka’a, but Gwen LeTutor has a great rundown on the Kanaha, where he briefly compares all three BRM v2 models – and he agrees that the Kanaha is the most versatile of the three. That said, if you’re doing constant laps in waves with less upwind work, want the absolute maximum agility and packability, or a bit more low-end grunt, we recommend checking out the BRM Ka’a.

Maliko V1 with bar mod. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Just by the way, after testing all the other wings for this guide, we did compare the Kanaha to the OG v1 Maliko, the parawing that launched them all, and we were surprisingly impressed. Greg recently announced a “Maliko V1.2” tuning modification that owners of the original Maliko can apply to their parawings, giving the wing considerably more upwind ability and range in the high-end, and bringing it up to par with some of the best parawings on the market. The Kanaha is hands-down a better parawing, – it turns better, goes upwind better, has shorter, color-coded lines, and the cool compact bar – but given how far the category has come in the past year, it’s incredibly impressive that this very first parawing launched in August of 2024 is still highly competitive. If you’re looking for a low-cost, entry-level parawing, we wouldn’t hesitate to recommend the Maliko V1.

The nuanced, elegant feel of the Kanaha reflects our experience with BRM’s ground-breaking strutless Cloud kites. The parawing responds with great sensitivity – in a good way – to micro movements as you fine-tune the trim, and – again like the Cloud kites – steers quickly, intuitively, and with a light touch. One final thing to note about BRM is the fact that it’s a small outfit, and a lot of BRM fans love the direct connection they feel with the founder, designer, and owner, Greg Drexler, and the riding community that’s formed around BRM kite, wing, and parawing riders over the years.

Check price on Board Riding Maui

Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

The “Pop-Out” Freeride Machine

Flysurfer POW

Sizes: 1.7 / 2.5 / 4.0

Size Tested: 2.5m

Price (4.0m): $899

Defining Characteristics: Ergonomic J bar, wide size spacing, pulley bridle

Pros: Widest wind range, crazy low end, comfortable, stable, ergonomic bar, goes upwind bonkers fast

Cons: Very long lines on the 4m, larger bar

A wind- and foil-sports brand known for their race kites and inflatable wings that’s part of Skywalk, a well-regarded paraglider brand, Flysurfer’s Pop-Out Wing (POW) parawing came out in June 2025.

Flysurfer went for a mid-aspect, semi-rounded wing shape similar to the F-One Frigate (and Flow D-Wing), but with a few unique twists. First of all, Flysurfer has succeeded with a pulley bridle, resulting in what is probably the widest wind range of all the parawings we tested. It’s hard to compare performance across different sizes, and the POW is one of the few parawings we tested in the sub-3m range. As such, it was very impressive that we were able to get up on such a tiny parawing when LEI wingers were on 3’s and 3.5’s! We haven’t had the chance to fly the 4m POW yet, but we’re impressed with Flysurfer’s confidence in putting out their parawings with such a big spread between the 2.5 and 4m, which shows how wide they believe the wind range of each size is. The POW also excels as a free-race machine, with outstanding upwind speed and angles.

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

The bar is different too – the only truly asymmetrical bar on the market to date. The Flysurfer bar is longer than most at 43cm / 17in and has an upturned “J” shape where your leading hand rests. This bend in the bar provides a uniquely comfortable position for the front hand, especially when ripping upwind and heavily powered. We love the ergonomic design, but the length of the bar does have a downside in terms of packability.

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Another key difference is the line length: at 157cm / 62in the lines on the 2.5m POW are longer than many other larger wings, and the line set on the 4m POW is very long at 210cm, which is longer than anything else on the market, and longer than most people are going to want for frequent stash-and-redeploy riding. However, for free riding, the longer lines are a feature, not a bug, and the wide usable wind range means that the POWs can be used effectively as inflatable wing replacements.

While the lines are a bit longer, the wing of the POW itself compacts beautifully when you collapse it, automatically folding in a perfect concertina pattern, making for easy douse and refly. In part due to its size, the tiny 2.5m that we tested showed outstanding agility as well.

In short, if you like the J bar, you can deal with the longer lines, and you’re willing to trust Flysurfer on the sizing, a three-POW quiver sounds like a great choice to us!

check price on MacKite

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

The Rock-Solid Ripper

Ozone Pocket Rocket

Sizes: 1.9 / 2.4 / 3 / 3.6 / 4.3 / 5

Sizes Tested: 3, 3.6 & 4.3m

Price (4.3m): $1,059

Best For: Downwind, laps, swell, free riding

Defining Characteristics: “Spanwise bridge lines” distribute load from the bridles

Pros: Fast upwind, very stable, comfortable, versatile, powerful

Cons: Somewhat softer, longer lines, bar is a bit long, less low-end

A global brand and leading producer of kites, wings, and paragliders, Ozone introduced their first-generation Pocket Rocket parawing in early 2025.

As we would expect from Ozone, with their deep expertise in kites, wings, and paragliders, the Pocket Rocket succeeds on almost all fronts. Ozone took the time to develop a product that addresses feedback from many early parawing riders, and the PR delivers outstanding performance across almost all of the criteria that we analyzed in our testing.

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

This relatively high-aspect parawing is as stable, powerful, and fast as a parawing can be at this early point in the development of the sport. It drives forward in the window, positively rips upwind, and handles being overpowered incredibly well. The handling is intuitive if a little less nimble than the BRM, and has a bit more of a kite-like feel with the longer lines.

The Ozone feels carefully and beautifully engineered. It’s impossible not to be impressed with how it flies, reflecting Ozone’s deep background in industry-leading parafoil kites and paragliders. To us, the Pocket Rocket feels like a glider – it flies incredibly cleanly, and feels fast and efficient even before you hit the water.

Our main criticism of the Pocket Rocket involves the lines. At 52 inches on the 3m and 64 inches for the 4.3m, the bridle lines could be shorter for riding that involves frequent wadding and redeploying. Ozone also went with a softer line material than the stiffer, sheathed lineset that the other leaders use, for example. The softer lines are more prone to getting caught on parts of your harness, and it’s a bit trickier to redeploy without twists or tangles. Some riders have shortened and/or treated the lines to make them stiffer.

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Along with the parawing, Ozone has produced a complete, highly refined package with a beautifully designed bar, harness line, and harness/belt that all work perfectly together. The rock-solid, slippery, composed, powerful ride of the Pocket Rocket is pretty much a can’t-miss, and we don’t hesitate to recommend this wing – especially to taller riders or people with long arms who won’t mind the longer lines, or those who prefer a bit more speed over agility and packability.

check price on MacKite

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

A Solid All-Rounder

Flow D-Wing

Sizes: 2.5 / 3 / 3.7 / 4.2 / 5.5

Size Tested: 4.2m

Price (4.2m): $869

Defining Characteristics: Excellent wing shape, solid construction, paraglider lineage

Pros: Powerful, stable, good low and high end, durable construction

Cons: Wingtips fold when overpowered

A well-regarded paraglider brand based in Australia, Flow introduced their D-Wing parawing in early 2025.

While Flow is a newcomer to the foil-sports world, they’re a well-respected paraglider outfit, and so it’s no surprise that they’ve produced a very good parawing. The D-Wing is a great all-rounder with rider-friendly flying characteristics, good power at both the low and high ends of the wind range, and solid construction. While it’s not the most compact or the most nimble, it’s remarkable for being such a good performer, especially as a v1 product.

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Our 4.2m test unit flew perfectly right out of the package, pulled hard at the low end, was responsive in turns, and had good stability and upwind performance. When it came out before the BRM v2’s, the Flow was the first parawing that could be flown ‘off the A’s’ to manage being heavily powered going upwind, and while the wing remains stable, the wingtips begin to fold into what’s known in paragliding as a “big ears” configuration. This does provide an effective means of handling power, but we found the BRM, Ozone, F-One, and Flysurfer parawings to perform better at the highest end of the wind range. Flow has some updates in the works for greater stability, depower, range, and upwind capability, which should become available as we get into the back half of 2025.

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Other things we like about the D-Wing are the solid, comfortable bar, color-coded canopy, lines, and bar, excellent line feel, very intuitive, consistent trimming and steering, good upwind angles and speed, wide powerband, and the structure of the wing, which allows it to be pumped at the low end. Overall, we like the Flow as a good value and a great all-around parawing, especially if you ride in an area with fairly consistent wind.

check price on MacKite

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Best “Budget” Parawing

Aeryn P1

Sizes: 3 / 4 / 5m

Size Tested: 4m

Price (4m): $654

Defining Characteristics: Low price, straight-run Dymeema lines

Pros: Powerful, stable, good low-end, durable construction

Cons: Not as packable, balks at going upwind at the steepest angles

A new outfit owned by the parent company that owns several water sports brands, including Windsurfer, Exocet, and Loftsails, Aeyrn announced their P1 parawing in May 2025. The P1 has some innovative features, in particular the spliced Dyneema bridle lines that all run in single, equal-length sections down to split pigtails very close to the bar. The net result is a comfortable, nimble, intuitive, well-rounded parawing that is a pleasure to fly, with plenty of low-end power, stability, and solid performance at a very low price point.

With its low-mid aspect ratio, the Aeryn isn’t designed to excel at the highest upwind angles, and during our testing, we were able to outrun the wing when pushing hard and fast upwind, resulting in back-stall and the need to bear off, reset, and regain speed. Aside from that, the wing flies beautifully and generates power smoothly and reliably, with solid grunt, stability, trimming, feedback, and excellent steering.

The polyester material does not absorb water; however, the canopy material is relatively thick, and the wing doesn’t concertina as easily as many others. The lines are very comfortable to handle, but they are also quite slippery, and at 145cm / 57in the lines are a bit longer than ideal, all of which means that dousing the Aeryn is bit of a two-step job, and the resulting package isn’t very small, especially compared to some of the more packable wings on the market. That said, re-deploy is very clean and reliable, in part thanks to the straight, low-friction lineset.

The leading edge and the pigtails are color-coded, but the bridles are all the same color. The bar is very comfortable, a good length, and we appreciated that the bridle attachments are secure and don’t get moved around unintentionally.

The Aeryn is even less expensive than the Flow D-Wing, our “value” winner, but the D-Wing has the same low end and does better upwind and is much more packable. Still, the Aeryn P1 does the job well and is a solid choice if budget is your top priority and you can live with some minor limitations on upwind performance and packability. There are certainly cheaper parawings on the market, but either we’ve been unable to get our hands on them, or have heard they’re not worth the effort. Congratulations to Aeryn for developing a very nicely designed and built v1 parawing!

check price on Mackite

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

An Interesting Parawing Alternative

F-One Plume K-Wing

Sizes: 2.5 / 3 / 3.5 / 4.2 / 5m

Sizes Tested: 4.2 & 5m

Price (4.2m): $1,049

Best For: Cruising, riding swells, upwind/downwind, learning to parawing

Defining Characteristics: A tiny inflatable kite (K-Wing) on very short lines that works a lot like a parawing

Pros: User-friendly, very stable, incredible top end and range, half the weight of an inflatable wing

Cons: Not much low end, can’t pack down and stow like a parawing

A global brand with a full suite of wings, kites, boards, and foils, F-One announced its Plume K-Wing in early 2025.

It’s fair to say that nobody expected a tiny little LEI kite to be in the mix when we made plans for this guide, but F-One had a surprise up their sleeve, and the Plume really works. While it isn’t a parawing, the Plume provides much of the same functionality, while being more accessible, stable, comfortable, and secure, especially for anyone coming from a kitesurfing background. There’s something about the complete collapsibility of parawings that makes a lot of riders feel kinda sketchy, and having an inflated leading edge is like a security blanket.

The overall power delivery is roughly similar to a parawing, but with even more limited low-end and increased top-end range. As confirmed by our testing, F-One recommends that you go up one full size in the Plume from whatever wing size would be appropriate for the wind strength. At some point, of course, you actually will become overpowered, but we didn’t really get there in our testing – the 4.2m Plume worked perfectly right up to 30 knots with no fluttering, no luffing, no bad behavior at all, really. Impressive!

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

The Plume isn’t intended for hardcore downwind foilers who want to pack a parawing away for long runs. But for everyday riders, this small, stable, intuitive inflatable wing may be very attractive as a stepping stone – or a full-on parawing alternative. The Plume feels much lighter and less cumbersome than an inflatable wing when flagged out, but of course, it’s not as compact as a parawing.

While the bar pressure on the Plume is so light that, for the most part, you don’t need to use a harness, we started to feel like it would be useful when more heavily powered, and F-One does have a harness and dedicated harness line in development. We rigged the Plume with a simple harness line, and it worked well.

Overall, we love that F-One had the vision to develop the Plume and offer it as an option. Especially for riders coming from kitesurfing as opposed to winging, it offers a way into parawing-like riding—more foil-power and less wind-power, while also covering a wide range of freeride conditions. Two Plume sizes could cover a massive wind range; they pack down pretty small, and while they do need to be inflated, you don’t need a full-size kite pump, so your travel package would be very compact.

Read our full review of the F-One Plume here.

check price on MacKite

Photo: Nicolas Ostermann

Other Parawings on the Market

There’s a lot of hard work and some innovative features in other parawings we looked at, so let’s give them a quick look.

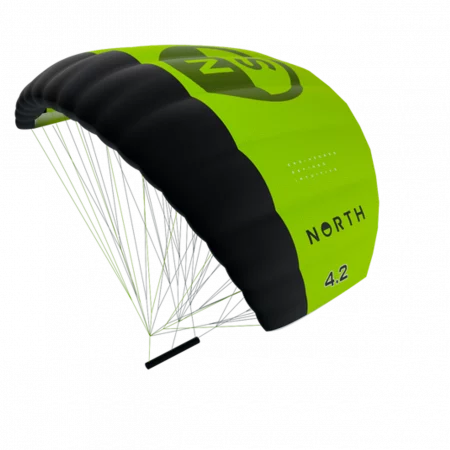

North Ranger

Sizes: 2.2 / 3.2 / 4.2 / 5.2m

Sizes Tested: 4.2m

Price (4.2m): $709

Defining Characteristics: No leading edge battens, comes with a stash backpack

Pros: Plenty of low-end, lightweight, well-priced parawing that packs easily

Cons: Not the best upwind performance

Another global brand with a wide range of wind- and foil-sports offerings, North released their Ranger parawing in early 2025, advertising it as a low-cost wing designed for “ease of flying, accessibility, and packing a lot of power per square meter” for downwinding and as a rescue backup.

We tested the 4.2m size and were impressed with the solid, straightforward construction and the clean three-line bridle-bar connection. The wing produces great low-end power for getting up on foil, but for our riding conditions, we found it to have relatively limited upwind ability. North acknowledged that strong upwind performance wasn’t in the design criteria for this first edition parawing, and that they are already working on updates and designs for other segments of the market. One trick we’ve seen that may help the upwind ability of the wing is to loop the front lines around the end of the bar to help the wing fly further forward in the wind window.

That said, for situations where strong upwind performance isn’t a necessity, the Ranger shows lots of promise. The very impressive low-end grunt of the wing and easy packability due to the lack of battens make it a compelling choice for downwinding, as well as wave-riding, and the price and included backpack make it an incredible choice as a rescue backup.

check price on MacKite

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Duotone Stash

Sizes: 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6m

Sizes Tested: 3m & 4m

Price (4m): $929

Defining Characteristics: Tiny pack size, double-skin wingtips

Pros: Great bar, very compact pack size

Cons: Stability when overpowered, center line connection can shift around

A global brand with a full suite of wings, kites, boards, and foils, Duotone announced its Stash parawing in early 2025.

We like the lightweight canopy material of the Stash, and the wing flies quite nicely, trims well, and goes upwind pretty well. We also like the thickness, length, feel, color coding, and curved ends of the very well-designed bar. One standout feature of the Stash, compared to others on the market, is the double-skin wingtips, intended to improve stability and help the wing hold its shape better in gusty conditions.

However, there were a few points about this wing that kept it out of our top picks. We’d like to see stiffer, thicker bridle lines to help reduce tangles and snags. Also, although some riders may be interested in the Stash’s tune-ability given the movable center line connection, we found that the center line on the Stash moves around too easily for our taste. Finally, stability when truly overpowered isn’t this wing’s forte, as we experienced some hunting and jumpiness at the upper end of the wing’s overall wind range. All that said, the lightweight packability of this wing makes it a compelling choice for downwinders and surfing in waves.

check price on MacKite

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

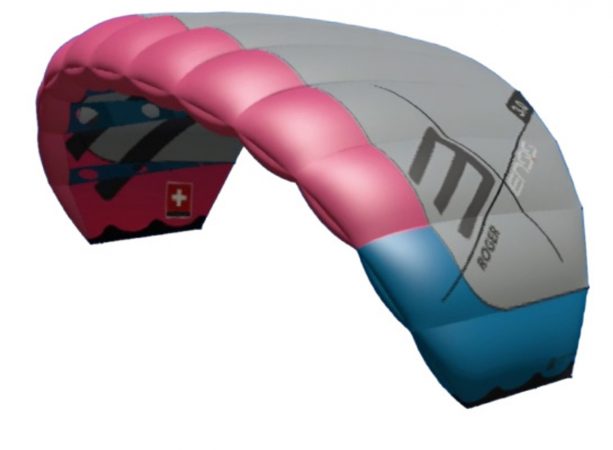

Ensis Roger

Sizes: 2 / 3 / 4 / 5m

Sizes Tested: 3m (V1)

Price (4m): $1,079

Defining Characteristics: B-line safety depower/leash connection

Pros: Some of the best color-coding we’ve encountered

Cons: Stability when overpowered (V1)

A smaller wing- and foil-sports brand based in Switzerland, Ensis was the second to market with their Roger parawing in late 2024. The V1 Roger had some well-thought-out features like the B-line safety connection and color-coded, rounded bar, but it also suffered from a lack of low-end power and relatively poor stability when heavily powered.

However, Ensis has already announced the V2 version of this parawing, the Ensis Roger V2, also branded as the 2025 Ensis Roger. While we have yet to get our hands on the new design, trusted sources who have managed to do so are reporting big increases in top-end stability, better low-end performance, and improved user-friendliness overall. We’re excited to try the new version and see the improvements for ourselves.

check V2 price on MacKite

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Best Parawings Comparison Table

Jump To: Top Picks | How We Tested | Buyer’s Guide

| Parawing | Sizes | Price (4m) | Weight (4m) & packability | Pros / Key differentiators | Cons |

| F-One Frigate | 2.5 / 3 / 3.5 / 4 / 4.7 | $1,049 | 640g Good packability |

Lots of range and speed. Dynamic bridle system. Depower tab. Includes harness line. | Lines can pinch hand when overpowered. |

| Boardriding Maui Kanaha | 2.5 / 3.2 / 4.0 / 4.7 / 5.5 / 6.2 | $1,000 | Lightest wing we tested @ ~500g. Most packable. |

Light, stable, nimble, intuitive. Quiet when overpowered. Most compact bar & only bar with space in front of A lines. Shorter lines. | Some may prefer a longer bar. Not quite as fast upwind as Ozone. |

| Flysurfer POW Pop-Out Wing | 1.7 / 2.5 / 4.0 | $899 | 650g Good packability, but long lines. |

Ergonomic J-shaped bar with pulley and rounded ends. | Bar is too long to pack easily, lines are longer than ideal. Big gap between 2.5 and 4m. |

| Ozone Pocket Rocket | 1.9 / 2.4 / 3 / 3.6 / 4.3 / 5 | $1,059 | 600g Very packable, but longer lines. |

B-line rib connection. Very stable, light, fast, powerful. Handles being overpowered very well. Goes upwind like mad. Best VMG. | Long, soft lines. Slightly less compact than the BRM wings. |

| Flow D-Wing | 2.5 / 3 / 3.7 / 4.2 / 5.5 | $869 | 700g Good packability |

Stable, intuitive, well-built. Solid low-end power. | Handles being overpowered, but the tips flap and make noise. |

| Aeryn P1 | 2.5 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 | $654 | 600g Ok packability |

Low price, Dyneema lines, stable, good power. | Heavier canopy material. Balks at going hard upwind. |

| F-One Plume K-Wing | $1,049 | 1000g. Not packable, but can be flagged out. |

Easier to fly, more stable, wider wind range than most parawings. | Doesn’t pack down like a parawing. | |

| North Ranger | 2.2 / 3.2 / 4.2 / 5.2 | $810 | 650g Moderately packable |

Depower tab. Comes with a backpack. | Doesn’t go upwind super well |

| Duotone Stash | 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 | $1,029 | 600g Very packable |

Ultra-light canopy and lines, very packable. Curved bar ends. | Doesn’t handle being overpowered well. |

| Ensis Roger (V1) (V2 avail. here) |

2 / 3 / 4 / 5 | $1,079 | 600g Moderately packable |

Ultra-light lines. Curved bar ends. Safety depower mechanism. | Jumpy. Heavier canopy material. Doesn’t like being overpowered. |

Laying out options for an afternoon of testing at Crissy Field. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

How We Wrote This Guide

Our lead writer for this guide is Bowen Dwelle, a San Francisco native and lifelong sailor. He’s a windsurfer, kitesurfer, kitefoiler, wingfoiler, adventure guide, and writer. Bowen has logged thousands of miles of high-wind foiling in San Francisco, Brazil, the Philippines, Mexico, and elsewhere over the years.

He brings all of his experience to bear, along with hands-on experience and testing, meticulous research, and many conversations with parawing designers and experts, including Greg Drexler of Boardriding Maui, Matjaz Klemencic of Triple Seven, Matthew Hoffman from Naish, Daniel Paronetto of the Lab Rat Foiler podcast, Cynthia “Cynbad” Brown, John Heineken, Dmitry Evseev, and others.

Will Sileo, Managing Gear Editor at The Inertia, also contributed to this review with testing, photos, conversations, in-water swaps, and comparisons at Crissy Field.

Just a few of the parawings we tested for this review. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

We tested all of the parawings we could get our hands on for two months, back to back, in wind from 14 to 30+ knots, evaluating many characteristics including ease of use, comfort, agility, stability, collapse, relaunch, packing, bridle, lines, speed, upwind angle, low end, high end, usable wind range, the bar, and overall versatility.

At this relatively early stage in parawing development, there are still many models that do well in certain conditions but not others, and there aren’t that many wings that we’d reach for in widely varying real-world on-the-water conditions. There’s definitely a place in the market for specialized parawings for specific disciplines, but at this point, we believe the reality is that most riders want an all-around parawing that does everything pretty well. Even though parawings were invented for downwinding, we’re finding that lots of riders want to know if it’s possible to straight-up replace their inflatable wing quiver with parawings.

Gliding in lighter winds under the iconic Golden Gate Bridge. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Based on our experience while testing, the most critical factor for all-around usability – and the most difficult to achieve for designers – is that, along with all the other features, the parawing must remain stable and usable when heavily powered so that it has a relatively wide usable wind range. At this point, the few parawings that combine good performance across the board with this key ability to upwind hard and fast are the F-One Frigate, BRM Kanaha, Flysurfer POW, and the Ozone Pocket Rocket, but these wings are all quite different.

The Frigate has the perfect combination of overall speed, low- and high-end power, and all the details like the lineset, line length, bar size, and harness line. On the other hand, the Kanaha has max agility, packability, minimalism, and a more nuanced feel due to a much less structured build that reminds us of the BRM Cloud kites. Stack your chips with the Pocket Rocket if you want more of an engineered machine, while the POW includes some unique choices like longer lines, the unique ergo ‘J’ bar, and the wide size spacing. All four go upwind like crazy and do the parawing thing very, very well, so take your pick!

Riding bumps outside the Golden Gate Bridge with the F-One Frigate neatly collapsed. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

What’s Next / The Future of Parawinging

2025 is the first full year for parawinging as a sport, and so we’re still in the early-adopter phase for sure. Everyone is curious, the stoke is high, and designers are innovating like crazy. As mentioned above, parawing gear is still in very rapid development, and many of the brands covered here, including BRM, Duotone, Ensis, Flow, North, Ozone, and Triple Seven, have said that their parawing offerings will be updated again soon.

Looking farther out, we see several things happening over the next couple of years:

- Wider wind ranges and greater all-around performance

- Some inflatable wing riders fully transition to parawings

- Continued development of parawinging disciplines, especially free-ride and racing

- More double-skin parawings

All smiles after a killer session on the BRM Kanaha. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Parawing Buyers Guide

Return To: Top Picks | Comparison Table | How We Tested

Navigate To: Parawing Disciplines | Parawing vs Inflatable Wing (and K-Wing) | Selecting Parawing Gear | Learning to Parawing | Parawing Technical Details

We’re here to help you make finding the equipment that fits your style an enjoyable and stress-free part of your riding journey. The most important variables in determining which parawing setup is going to work best for you are:

- The parawing disciplines you’re interested in.

- Your skill level and previous experience in winging, kite-foiling, and other foil sports.

- Your weight (don’t forget to include wetsuit & equipment).

- The conditions that you expect to ride in.

- Which aspect of performance is most important to you in your equipment—speed, versatility, glide, ease of use, maneuverability?

- What’s your personality as a rider—racer, gearhead, ‘keep it simple’ kind of rider, or somewhere in between?

- Your budget.

Overall, it’s pretty hard to go wrong if you use this guide and honestly assess your athletic ability and ambitions, talk to some reps and other people in your local riding community, and – most of all – follow your intuition towards the gear that fits your personal riding style.

Redeploying the F-One Frigate. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Parawing Disciplines

The first and most important question in selecting a parawing is: how are you going to use it? Are you going to be packing the wing away for extended downwind foiling, using it for short laps in sets of waves, long upwind runs, or free-ride reaching back and forth with occasional riding of swells and bumps?

Keep in mind that while parawings can be used as replacements for inflatable wings, they make power differently, and the riding styles that work best with parawings are different. You can use a parawing like an inflatable wing, but, just as with the transition from kite-foiling to winging, a big part of parawinging is that it opens up new ways of riding.

Downwind Foiling

This is the original use case for a parawing – use the wing to get up on foil, and then pack it away for a long downwind run, playing the infinite chess game of connecting bumps without any other power source. A parawing with plenty of power and easy, maximal packability is ideal for downwinding.

A harness isn’t really necessary; just somewhere to pack the wing (and perhaps carry a second one, along with some water, food, radio, phone, safety gear, and maybe a paddle!). For pure downwinding, we like the BRM Maliko 2 and Kanaha, the Duotone Stash, and the Ozone parawings best due to their superior packability. The North Ranger also deserves a look.

Short Laps In Waves

Many riders are also using parawings for quick laps or runs in swell, waves, and wakes where they “douse” or collapse the wing and then hold it loosely “wadded” or balled up while riding purely on foil for a short time before quickly redeploying the wing. In these situations, it isn’t practical or necessary to pack the parawing away, and so a design that makes it easy to douse and then re-fly the wing reliably and quickly is what you want. We recommend not using a harness line for short laps in waves, as it’s not needed and just presents another place where the bridle lines can get caught. The BRM Kanaha and Ka’a, and the F-One Frigate are our top picks in this category, although the Ozone, Flow, and Aeryn parawings would work well too.

Flying off the front lines is critical for an upwind-oriented parawing. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Long Upwind/Downwind Laps

One of the most attractive uses for parawings is for combined upwind/downwind runs. For this sort of riding, you want a very stable wing that flies forward in the window, drives hard upwind, and handles being overpowered well, because going upwind generates the most apparent wind, and therefore the most ‘overpowered’ feeling. You will certainly want a harness so you can hook in for this sort of riding. You may want to pack the wing away on downwind legs, but parawings designed for this discipline can afford to be a bit bulkier, in a trade-off for stability and upwind ability. The F-One Frigate, Flysurfer POW, BRM Kanaha, and Ozone Pocket Rocket all fit the bill in this category, along with the Flow D-Wing and the F-One Plume.

Free Riding and Cruising

Although parawings were originally intended to be packed away once on foil, it’s inevitable that many riders are going to use them in place of inflatable wings for free riding and cruising in conditions that mostly involve reaching back and forth, carving turns on whatever bumps and lumps happen along the way. For free riding, you want a stable, user-friendly wing that excels at reaching and going upwind. You’ll want as wide a wind range as possible, and packing the wing isn’t really a factor. For free riding, we like the F-One Frigate, Flysurfer POW, Ozone Pocket Rocket, BRM Kanaha and Ka’a, Flow D-Wing, Aeryn P1, and the F-One K-Wing.

Freestyle & Racing

Some riders are already demonstrating that parawing freestyle is possible, but at this point, it’s still too early to say what sort of parawing will be best for freestyle. As for racing, parawings have some major potential. We’re already seeing the first parawing racing events emerge, and of course, there’s predictable minor controversy about whether parawings can race alongside wings, but one way or another, it’s gonna happen. Racing parawings are likely going to be double-skinned designs that draw heavily on ram-air kites like this Flysurfer proto flown by Théo de Ramecourt or the Triple Seven P.T. Paratow.

Rescue/Backup

Another legit use for parawings is as a backup power source for offshore downwind missions, or just to carry a second size. Although you can carry a second parawing in the waist belt/harness, that of course makes it impossible to stow your primary parawing there, and quite a few riders have reported losing parawings stowed this way after crashing. A better solution is to carry your “get back” parawing in a backpack. One rider we know carries a 5m getback parawing in a compact dry bag inside a cheap string backpack under a rash guard. The idea is to keep the secondary wing dry and out of the way, and the rashie covers everything to keep it out of the way on the water.

Yet another solution could be a hybrid harness/backpack like the Ride Engine chest harness mentioned elsewhere in this guide (although it’s a bit small for wings 4m and above). Larger-capacity running backpacks are a great option that we’ve seen some riders make use of as well. The North Ranger comes with a backpack that the wing can be stashed in for such situations.

Wing, K-Wing, or Parawing? Photo: Nicolas Ostermann

Parawings vs Inflatable Wings (and K-Wings)

Especially for those of you coming to parawinging from inflatable wings, keep in mind that a parawing is a different kind of power source. They were originally invented for downwinding, a discipline that generally involves using foils with more glide than we typically use for winging, which in turn means that you can use a smaller parawing with such foils. You can use a parawing like an inflatable wing – with small boards and foils – but you’ll spend a lot more time heavily- or over-powered because of the narrower sweet spot in the wind range.

Said another way, don’t start by looking at parawings as 1:1 replacements for inflatable wings. Just as wings involved a new kind of riding from kite-foiling, parawings are different from wings, and as Dan Paronetto of the Lab Rat Foiler podcast said recently in this conversation with Ken Adgate, one way to look at that difference is that “the beauty of the parawing is when it’s not flying,” because we tend to ride powered up most of the time when out winging; with parawings, we’re inclined to use the foil more, and to use the wing as little as possible.

Here’s our take on how these power sources compare:

Parawing

A small parafoil kite (or “wing”) flown on very short (1-1.5m) lines, with a control bar. Various alternative and brand names exist, but it seems clear that “parawing” is going to stick as the term for the overall category. Parawings are roughly ¼ of the weight and much more compact than inflatable wings, but overall, where the designs currently stand, they still have a narrower sweet spot in their usable wind range.

Don’t discount the F-One Plume. While it doesn’t pack down like a parawing, it’s a real joy to ride. Photo: Nicolas Ostermann

K-Wing

Named for the fact that it’s a hybrid between a kite and a wing, a “K-Wing” (as recently introduced by F-One) is a small, low-aspect leading-edge inflatable kite flown on very short ~1.5m lines, with a kite control bar. You can’t pack it away while riding like a parawing, but a K-Wing can be flagged out behind you like an inflatable wing. The K-Wing is about half the weight of an inflatable wing. See our section above on the F-One Plume K-Wing for more info.

Inflatable Wing

A vertically-oriented leading-edge inflatable (LEI) sail that is held directly by handles or a boom on the center strut. Also known as a “hand wing” in some circles, or more often just a “wing.”

| Parawing | K-Wing | Inflatable (LEI) wing | |

| Athleticism | More than with LEI wings | More than with LEI wings | Less than parawinging, for sure |

| Wind range | Narrower wind range; less low-end power than LEI wing, some are easily overpowered | Much less low-end power than LEI wing, but very high top-end range | Wider wind range than most parawings; good low-end power and high-end range |

| Stability | Some become unstable when heavily powered, but the good ones are very stable | Very stable | Very stable |

| Upwind riding | As good as LEI wings | Better than most parawings | Very good |

| Downwinding | The best! | Less cumbersome than an LEI wing when flagged, but not nearly as good as a packed-up parawing | Can flag out, but the wing can be cumbersome and get in the way |

| Wave riding | Can be great, requires more skill | Good for swell | Very good |

| Free riding/ cruising | Can be great with the right gear | Can be great with the right gear | The best! |

| Freestyle | Still emerging | TBD | Oh hell yes |

| Racing | Still emerging, but will happen | TBD | Lots of it |

| Bar pressure | Most riders use a harness upwind | Very light; no harness required, but can be useful for upwind | Most riders use a harness upwind |

| Weight | ~0.6 kg / 1.3 lb | ~1 kg / 2.2 lb | ~2 kg / 4.5 lb |

| Compactness | Much more compact than LEI wings | More compact than LEI wings, less compact than parawings | Bulky, especially wings with booms |

| Simplicity | No center strut, no LEI bladders, no pump – but many bridle lines. | No center strut, but there is a bladder that requires a small pump. | No lines, but bladders require inflation. |

| Versatility | Best for downwinding, not as good for free riding. | Not really better than a parawing or an inflatable wing for any specific discipline, but requires less skill than parawings | Excellent for many disciplines; not as good as a parawing for downwinding. |

| Visibility | Much better view than LEI wing | Much better view than LEI wing | Downwind view blocked by wing |

| Durability | TBD on long-term durability, but no risk of puncturing a bladder and less risk of damaging the wing | Probably a bit less risk of damage than with an LEI wing | Proven long-term durability, although there is always the risk of puncturing a bladder or putting your foil through the wing |

| Cost | Less than LEI wings: 4m $700-$1,100 | Same as parawings | More than parawings: high-performance 4m avg $1,000-$1,800 |

| Board size | 110-120% of body weight in kg/ liters is ideal to cover a wide range of conditions. | 110-120% of body weight in kg/ liters may be ideal to cover a wide range of conditions. | 100% of body weight in kg/liters is ideal for many riders to cover a wide range of conditions. |

| Foil Size | Better with larger foils | Better with larger foils | Can use smaller foils than with a parawing |

| Travel | Very light and compact. Bring however many you need. | More compact than LEI wings, a bit more bulky than parawings; range means you can probably travel with just one or two sizes. | Bulky, especially wings with booms. Travel with two or three sizes. |

While your old wing board and foil might do the trick, getting your setup dialed for parawinging specifically will provide a much better riding experience. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Selecting Parawing Gear

Jump To: Top Picks | Comparison Table | How We Tested | Buyer’s Guide

The Parawing Itself

As obvious as the idea may seem in retrospect, parawings emerged when they did through a classic case of convergent evolution, thanks to a series of prior developments in kiting, winging, and downwind foiling that brought certain innovative riders to the point of envisioning a small collapsible power source that could be used to get on foil and then packed away for downwinding and wave riding.

There are already more than a dozen parawings on the market, and although the basic concept is the same, there are some important differences. If you’re choosing parawing gear for the first time, our recommendation is to keep it simple with a single-skin wing, a simple bridle layout, and color-coded bar, lines, and leading edge.

The last-minute introduction of the K-Wing as an alternative to true parawings throws an interesting twist in the decision process. For riders pursuing true downwind riding, a parawing is the obvious choice – but for those who won’t be packing the wing away, a small inflatable wing that offers more stability and security may be very attractive, especially for learning.

Of course, there are always going to be tradeoffs – the most packable parawing isn’t going to make the most power, nor is the most stable going to be the most nimble. Also keep in mind that while the downwind stoke is real, and parawings certainly broaden access to this style of riding, your own riding style may or may not call for packing the parawing away very often – or at all – so be sure to make your choice based on how you’re actually going to use the gear, not someone else’s mega-downwinder on Youtube.

Wake-thieving with the 3.2m Kanaha. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Wind Range/Low & High End

Any given size of sail, wing, or kite has an optimal wind range. Perhaps the most important thing to understand about parawings as power sources is that, at this point, while the best parawings have a total wind range that’s roughly similar to that of an inflatable wing, parawings still tend to have a narrower sweet spot in their usable wind range than inflatable wings. This means that, in general, for parawings, the “ideally powered” part of the wind range is narrower, and the portion of the wind range that’s in what we call the “heavily powered” zone is larger.

Since there’s a range between the sweet spot or ideal wind range and the truly overpowered zone, a wing is still usable when heavily-powered but not really when truly over-powered. In general, inflatable wings, kites, and K-wings handle being heavily powered much better, because parawings are more sensitive to apparent wind and deform more when heavily loaded and as they are sheeted.

The result is that the sweet spot of ideal power is something like 3/4 of the total usable range for inflatable wings (with the remaining upper quarter being heavily powered), and the sweet spot for parawings is only something like 1/2 of the usable range, with the other half being heavily powered.

Riders often talk about “grunt,” or the ability of a wing to generate power at the low end of its optimal wind range. Parawings pull differently, and they’re not rigid, so you can’t pump them as well as inflatable wings. Instead, you have to pump the board and foil as well. However, parawings with lower aspect ratios and sturdier inner structures have proven to be better at pumping.

The F-One Frigate is exceedingly stable when flown off the front lines. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

At the high end, and this is most important for upwind riding, you want a parawing that remains controllable and with manageable bar pressure as far as possible above its ideal wind range before becoming overpowered to the point of unpleasant, unmanageable, and potentially unsafe. Think about how it feels to be truly overpowered on an inflatable wing or a kite. At some point, it goes from feeling groovy to feeling a little too lit, and perhaps you can still hold it down, but then if the wind gets even stronger, at some point the thing just starts flapping and bouncing around, and you can no longer hold your line upwind.

Also – and this is very important – the effective wind range of a parawing has a lot to do with the board and foil you’re using and the type of riding you’re doing. More so than for other wind sports. Because of the narrow powerband of parawings, it’s really important to select a board and foil that are optimal for parawinging if you want to go upwind.

If you insist on using your normal wing equipment, it’s very likely that you won’t be able to get up at all unless you’re using a parawing of a size that results in being overpowered going upwind. And, relative to how LEI wings work, you will probably also feel underpowered until you get up on foil.

Our point here is that if you insist on using gear that isn’t well suited to parawinging, it won’t feel great – but if you select proper equipment so that you can ride in the lower-middle part of the wind range of whatever size parawing you’re on, you’ll have a much better experience. All of the above is most important for upwind parawing riding, much more so than any other type of parawinging. See Boards for Parawinging, below, for more.

The diagram below is a rough illustration of the approximate, relative power band of parawings, the K-Wing, and inflatable wings, given the same rider, board, and foil.

- Under: can’t get on foil, or only with great difficulty

- Ideal: most comfortable, light bar pressure

- Heavy: less comfortable, heavier bar pressure, less than ideal wing behavior

- Over: no longer enjoyable, can’t stay on the desired course, potentially dangerous

- The black arrow indicates the effective usable wind range

Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Most parawings of the current generation are manageable to some extent when heavily powered; it’s a question of how much less stable and less pleasant they become to use in that state, before becoming totally overpowered. The F-One, Flysurfer, Ozone, and BRM parawings were our favorites at the high end for upwind riding. By the way, the F-One Plume K-Wing blows all of the parawings out of the water with its huge top-end range. At the low end, the F-One, the Flysurfer, Aeryn, Flow, North, and the original BRM V1 Maliko have the most grunt of all, which could be important if you’re more focused on riding the smallest equipment you can downwind, rather than riding upwind. Of course, under- and over-powered are relative to so many other factors, and the ranges differ for each parawing, so use the above as a general guide at most.

The Flysurfer POW is another top-tier choice when it comes to upwind stability. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Stability

Some parawings jump around a lot and/or flap the leading edge or wingtips when heavily powered, and some just pull – stable, and quiet. In our testing, the most stable parawings were the F-One, Flysurfer, Ozone, and BRM, followed by the Flow D-Wing and the Aeryn P1.

Agility

The shorter lines on the BRM Kanaha and Ka’a make it possible to do some things that aren’t possible with longer lines, but then again, you can whip some of the more kite-like parawings like the Ozone and Flysurfer around in ways that you can’t with shorter lines. Similarly, some parawings – the BRM’s again, but also the F-One, Flysurfer, Flow, and Aeryn – can be flown upside down, backwards, and sideways, while others pretty much want to stay upright.

Stowability/Packability

Basically, simpler, lighter construction and shorter lines make a parawing more packable, and in this area, BRM takes the win, also because the lineset that BRM uses is less prone to tangles and knots. The Duotone Stash uses an even lighter construction that makes it perhaps even more packable, and so the Stash deserves a look in this category as well.

Short lines and a lightweight, minimal canopy construction make for great packability with the BRM Kanaha. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Upwind Ability

When parawings came out, the first question everyone had was: ‘Do they go upwind?’ If it’s not already obvious, they certainly do go upwind, in some cases even better than inflatable wings – but of course, there’s still some variation in how well. F-One, Flysurfer, and Ozone take the win here with max VMG (the combination of upwind angle and speed), with the BRM Kanaha and the OG v1 Maliko close behind. The Flow, Naish, and Aeryn go upwind well too, as long as they’re not too overpowered. The F-One Plume K-Wing, by the way, positively rips upwind when powered up.

Parawing Sizing/Quiver Building

As Tucker from MAC Kiteboarding lays out in this video, parawings “don’t deliver big low-end grunt like some traditional wings. They come alive once you’re moving and start building apparent wind, but they’re not going to yank you onto foil from a dead stop. Sizing for enough usable power is extra important – especially when you’re just learning.”

As for how the sizing compares, at this point, we’re seeing that the sizing for the leading parawings is roughly comparable to inflatable wing sizing, and perhaps even a little smaller. There were days during our testing when we were on 3m parawings and most wingers were on 3.6m wings, and days when we were overpowered on 3m parawings and wingers were good on 3m wings. That said, we’re also following our own advice and riding bigger boards and foils than we would use for winging.

Will Sileo’s quiver for parawing riding in the SF Bay: Kanaha 2.5 and 3.2m, and a V1 Maliko 4m with Greg Drexler’s latest tuning mods for enhanced performance. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

With the above notes about board and foil size in mind, you’re probably going to end up with more or less the same size of parawing as an inflatable wing, for a given wind strength. Let’s say, for example, that you’re comfortable on a 75-liter board, 700cm foil, and a 4m inflatable wing in roughly 20 knots at your local spot. In these same conditions, you would want something like a 90-100 liter board, 850-1000cm foil, and a 4m parawing.

We also agree that for most people, one or two parawings is the right number to start with, unlike the standard three-wing and three- or even four-kite quiver. We’re still very early in the development of parawings, and so it probably doesn’t make sense to invest in a ton of different sizes right off the bat, since new designs will come out in quick succession. Our recommendation is to start with one or two sizes: a 3m and 4m if you live in a windier area, or a 4m and 5m if you’re bigger and/or live in a less windy area. You’re not going to need a 2m parawing anytime soon unless you live in Maui, Hood River, northern Brazil, or some other places where it really nukes.

Cost and Resale Value

When parawings first emerged, there was a fair bit of chatter from folks who thought they were expensive, or that they should be cheaper than inflatable wings. Now that more of them are in people’s hands, it’s 100% clear that parawings are just as much of a complex, highly developed product as any other part of our wind- and foil-sports gear.

Our position is that, in general, manufacturers do their best to bring quality products to market and to price them competitively while maintaining their ability to make a reasonable profit, and that is what we see in the parawing market today. Since we’re still early in parawinging, new designs and product versions will be coming out in quick succession. At this point, don’t expect used parawings to hold their value very well. If your budget is limited, there are already plenty of used parawings on the market.

Midlength designs tend to be a great choice for most all-around parawinging. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Boards for Parawinging

The ideal board size for parawinging is going to depend on your skill level and the type of riding you’re doing, but in general, it’ll be bigger than your typical wingfoil board. Beginners, of course, will benefit from bigger boards, but the other reason is less obvious and even a bit counterintuitive.

As Gwen LeTutor lays out in this outstanding video on selecting boards, if you’re just using the parawing to get up on foil and then go downwind, you can use a smaller board because you can fly a parawing big enough to get you up on that small board and then douse it. If you were to use that same parawing to go upwind, you’d likely be overpowered.

With that in mind, if you’re riding upwind, you’ll want to use a larger board that you can get up on foil with a smaller parawing. This is so that once you do get on foil, you won’t be immediately overpowered due to the increased apparent wind.

In short, you’ll probably want a larger board if you’re doing a lot of upwind riding. The reason this is counterintuitive, and so hard for people to understand, is that you don’t need the larger board while you’re going upwind – you need the larger board to get up on foil with a small enough parawing that you’ll be able to groove upwind without feeling overpowered.

Will Sileo’s favorite board for parawinging has been the F-One Rocket Mid, 78L. Weighing 155 lbs himself, it’s just enough stability to taxi around on the parawing while waiting for a gust, while maintaining a playful, high-performance feel. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Downwind: smaller board, bigger parawing

Upwind: bigger board, smaller parawing

Because so many riders will be coming to parawinging from wingfoiling, it’s worth noting that the wind range of parawings still has a somewhat narrower sweet spot. Using my wing board for parawinging skews the usable power range of the parawing into the heavily powered part of the range, because I will have to use a larger parawing to get up on foil than I need to ride and go upwind. As Greg Drexler puts it in this guide, “When riding a board of lower efficiency, I’ll normally ride one, sometimes two, parawing sizes larger.”

That said, we’re already starting to have parawings that have close to the same wind and power range as wings. Therefore, our wing boards should work better (especially with a size up on the foil). Still, it sure is nice to be able to just stand on the board when you’re struggling to get going with the parawing!

I can use my 75-liter wingfoil board for parawinging, but if I’m doing much upwind riding, once I do get up, I’ll end up being heavily powered or overpowered much of the time. On the other hand, if I go parawinging in the same conditions on a 90-100 liter board, I can get up more easily, meaning that I can use a parawing size more in the lower-middle end of its wind range, which in turn means that I’m less likely to be overpowered during my session. You can access the full wind range of the parawing more easily and comfortably with a board that allows you to get on foil more easily.

Beginners and light wind riders will benefit greatly from a board range of 20-30 liters more than their weight in kilograms, e.g., if you weigh 176 lbs / 80 kg, you would want a board in the 100-110 liter range.

As for board shape, the mid-length trend for wingfoil boards that has emerged over the past couple of years will serve you well as you get into parawinging, since a longer waterline will allow you to generate board speed and get on foil more easily.

Surfy, controllable foils with plenty of glide like the Lift Florence 130X are great for parawinging. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Foils for Parawinging

As with winging, almost any foil can be made to work with a parawing, but in general and especially as you’re learning, you’re going to want something a bit larger than whatever your go-to is for wing foiling. As noted above, the effective wind range of a parawing is highly affected by the board and foil you’re using. The harder it is to get up on foil, the more power you’ll need in the parawing, which, if you’re hoping to go upwind once you’re on foil, will mean it’s more likely that you’ll be overpowered.

Just as with boards, this means that if you’re just using the parawing to get up on foil and then go downwind, you might be able to use a smaller foil because you can fly a wing big enough to get you up on that smaller foil and then pack the wing away. But then again, if you’re downwinding, your foil choice is probably going to be more about the swell conditions.

On the other hand, if you’re riding upwind, you may want to use a larger foil that you can get up on with a smaller parawing, so that once you do get on foil, you won’t be immediately overpowered due to the increased apparent wind.

Downwind: smaller board and/or smaller foil, bigger parawing

Upwind: bigger board and/or bigger foil, smaller parawing

For example, I most often use a Mikeslab 825, 700, or 600 for winging on a 78-liter board, and so for parawinging, I’ve mostly been using the Mikeslab 950 and 825 on 90 to 100-liter boards. Similarly, my much more svelte colleague Will Sileo often uses a Code 980 or 850 for parawinging on an 80-liter board instead of his usual Code 850 or 720 and 60-liter wing board. If I were strictly downwinding, I might put the Mikeslab 950 on my 78-liter board, but to me, the whole point of the parawing is to be able to downwind and then go back upwind. See our Foil Buyers Guide for more details on selecting foils.

Left to right: Ride Engine Chest Harness, Ozone Parawing Stash Belt, Ozone Wing Harness Line.

Accessories

Harness/Belt

A harness (aka “belt”) or backpack can be useful for two reasons: 1) to hook in going upwind and 2) to stow your parawing during downwind riding and/or carry a second parawing or other gear. It can be useful to have a second size with you on the water since the wind range is so narrow, and it’s easy enough to switch wings on the water if you have one packed away in a belt or backpack.

Ozone’s Parawing Stash Belt is one of our favorite parawing belts that we’ve tested. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

We recommend using a harness to hook in for repeated upwind/downwind laps or free-riding that involves a lot of upwind work. As with an inflatable wing, the bar pressure on a well-designed parawing is reasonable enough that you can go upwind without a harness, even heavily powered. Although the Ozone and BRM belts are designed to be used as harnesses, you might also take a look at the Ride Engine Free Float Chest Harness, which gets the harness hook up above the redeploy zone, and also makes it easier to fly the parawing low in the window when going upwind.

Ozone Stash Belt with a parawing stashed inside. Photo: Bowen Dwelle//The Inertia

Downwind: storage/equipment storage needed, but no harness/line/hook

Waves: nothing required, keep it clean to avoid tangles

Upwind: no storage needed (but can be useful to carry another size), harness highly recommended

Free Riding: wing storage and harness optional

Some brands are making parawing harnesses already, and we’ve found ourselves to be big fans of the Ozone Parawing Stash Belt, which we found to be the most comfortable and also very secure and flexible in terms of stowing the parawing. You may need to use pigtails to add attachment points for your board and/or wing leashes, or use a separate leash belt. You can also use a wingfoil harness, just keep in mind that you’ll be climbing on the board more often (especially at the beginning), and so you’ll want to be careful with the harness hook and/or use a soft or folding hook.

The Ozone harness line on the Flow D-Wing. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Harness Line

If your riding situation calls for a harness, you’re going to need a harness line – and since almost all riders are going to want to go upwind, almost all riders are going to need a harness line. Unfortunately, most parawings do not come with a harness line, which results in a lot of experimentation and, too often, riding with suboptimal trim due to bad harness line setup.

F-One’s Frigate comes with a harness line included. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Obviously you want something super strong, but also ideally with some stretch. Ozone’s Wing Harness Line is a favorite of ours, as is the PKS Parawing Adjustable/Universal Harness Line. BRM has a couple of options as well. You can also use 4mm Dyneema shock cord to make your own – just tie it on with two clove hitches. Here’s a nice little video about setting up your harness line and leash.

There’s a bit of a debate going on between stretchy harness lines and fixed harness lines. Fixed harness lines are easier to swing into your harness hook, especially when riding one-handed, whereas stretchy harness lines can help you stay locked in more securely, and are debatably lower profile.

A parawing leash isn’t necessary, but it’s nice to be able to let go of your parawing without fear of tangles, especially as you’re learning. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Parawing Leash

Opinions differ about whether to use a leash for the parawing itself. Most people agree that you don’t need a leash because if you let go of a parawing, it will simply fall in the water and not drift far. Not having a leash certainly keeps your setup cleaner, and so if you are dousing the wing frequently, especially in waves, we recommend not using a leash.

On the other hand, using a leash gives you the option of letting go of the bar to give yourself a rest, and stops the bar from getting tangled in its own lines when you let go of it, if rigged properly. It may also give you an extra level of security or comfort, especially while learning to parawing.

Some parawing bars, like on the Ozone and Ensis Roger, have a built-in way to attach a leash directly. Otherwise, just put a pigtail around the front or back end of the bar and attach a short dyneema shock cord leash from the pigtail on the bar to the front of your harness.

We’ve found footstraps to be beneficial for parawinging, but they’re certainly not necessary. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Foot Straps

Your call, and of course you can parawing strapless, but we prefer using foot straps as they help a lot with pumping the board and foil, especially while learning.

We highly recommend dialing in your parawing handling skills on land before hitting the water. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

Learning to Parawing

Jump To: Top Picks | Comparison Table | How We Tested | Buyer’s Guide

Experienced wingers and kite-foil riders will generally get up on their first few attempts parawinging. While parawings are entering the second generation of product development, overall, they are still a bit more difficult to use than inflatable wings (or kites). Prior experience winging, kiting, or foiling will help a lot. Either way, if you’re learning to parawing, make sure you have a larger board with a longer shape, a big, user-friendly foil, and a place to learn with strong, steady wind.

While everyone who’s heard about parawinging is excited about packing the wing away while downwinding, for most average riders, that’s going to be a long time coming. In reality, the most important new skill in parawinging is learning to pump the board and foil to get up. While inflatable wings can be pumped very effectively to get going at the low end of their wind range, pumping the wing doesn’t work nearly as well with parawings. Instead, you have to pump the board and foil – and since you’ll hardly be moving when you start, the technique is much more like a flat-water stand-up paddle foil start. We’ve found a front footstrap to be helpful, but it’s certainly not necessary. We’ll be honest: it can be very challenging at first, and it’s more athletic than pumping to get up with an inflatable wing.

If you’ve never foiled before, we’d recommend you give winging with an inflatable wing a try first. That said, parawings kind of fly themselves, and they are so much lighter than inflatable wings that with the right gear, there’s no reason not to go straight to the parawing if that’s what your heart is set on!

Parawing Skill Progression

There are plenty of tutorials out there on the interwebs about all of these already, but here are our thoughts and some key tips.

Ground Handling

Something that really helps with learning all of these nuances, as well as all the maneuvers such as gybing, tacking, and all the rest, is to practice “ground handling” the parawing on the beach. Any good paraglider pilot will tell you that time spent ground handling is paid back 10x once in the air—or, in our case, on the water.

Spend some time on land getting a sense of how your parawing reacts to sheeting in and trimming with the control bar. Photo: Will Sileo//The Inertia

The Wind Window – Sheeting/Trimming the Parawing

Because parawings fly on lines, they’re able to move around more in three dimensions than inflatable wings, and a bit more like kites. Higher aspect wings fly farther forward in what’s known as the “wind window,” generating more lift, and lower-aspect wings fly farther back, doing more pulling than lifting. Parawings also tend to be more sensitive to sheeting angle; you’re going to want to sheet in slightly for power, but it’s easy to oversheet and stall a parawing, which kills the lift and drops it back in the window. It’s useful to understand the concept of the wind window as you learn how any particular wing works, and dial in where it makes power.