As it all comes together.

I gave my brother the first five flies I ever tied for Christmas this year. Like the best gifts, a fly doesn’t necessarily cost much or require profound talent to construct. But a fly made to the best of the maker’s ability requires time and attention, which are the truest gifts we may bestow on something or someone. He will probably never use them, but I think he appreciates them. That’s all we can hope for in a gift, right?

A hand-tied fly is old-fashioned; fashioned in the sense that a hand passed over it and lingered. Fashioned in the sense of planned and honed and puzzled over. Such objects and acts are increasingly rare; let the hand that one day casts it appreciate the hand that made it. And let no one belittle you for the perceived quality of your fly. There is no objective measure of a “good,” “terrible,” or “excellent” fly. Some people spend so long tying their flies that they are reluctant to ever use them and instead display them in glass cases. Fish have been known to eat the “ugliest” of flies, tied by a novice who was probably called hopeless.

There is no superior fly, there are only those made by your own hand and those not. You should know the difference. Know the perfect of thread wound around the shank, coil brought against coil, of chenille bisected under the crosshatch of the thread. Know the trueness of the fletching that will guide it through the air. Know the symmetry of the knot that closes each preceding twist and turn, the match that burns any excess to bind the closure.

But I don’t hold fishing or tying a fly in such reverence. I find it beautiful and restorative in its lack of thought. I surrender to how it engages my senses and coaxes the gentlest movements of which my fingers are capable.

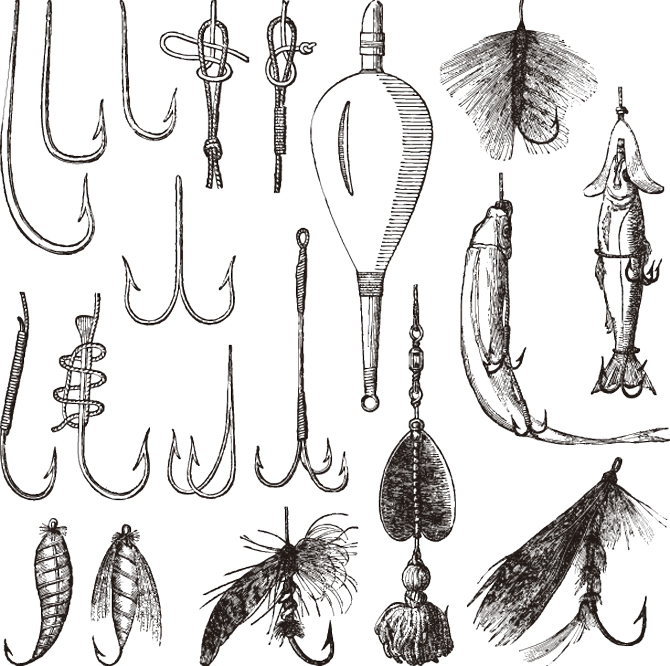

After all, consider the components of the fly. They are innocuous: filament, a hook, some odd feather, yarn, tinsel, or wax. The list reads like the contents of a long-forgotten coat’s pocket. None of these items has intrinsic value; none is even barterable. Yet, the act of joining them is its own alchemy. Think of it — four or five of these discarded items, bound with grace and élan. They are changed, from useless, to something utterly profound: our own attempt at simulating life and, if well executed, a means to satisfy and nourish us.

There is something deeply, eternally comforting about simple acts that we perform with muscle memory. Every day since I was born, the world has appeared more complicated. There is nothing essentially wrong with that realization, but it can be exhausting, even if you’re not as wistful as myself. If you are burdened by such thoughts, then you are also restored by simple acts that were fixed below the canopy of deliberate memorization but have since receded into learned movement. For someone far better at it than myself, I imagine tying a familiar fly must be so. It is like the cook who glazes a skillet while addressing an attendant. Or the barber who washes your hair diligently, without the sensation of fingers on his scalp.

Touch, perhaps the most essential and yet under-appreciated sense, is the pilot light of so many memories that we never recall until they recur. In folding, pinching, binding, and melting, your hands are performing the movements of which only we are capable. To construct anything, but even more so with the minute and fine, is to revel in our capacity to understand and manipulate. Manipulation, derived from the Latin for hand, is the act that makes us human.

There are fishermen who take an academic approach to fly tying, studying the weather patterns of a locale and the yearly emergence of certain insects from dormancy. There are some who believe the fly is the means to outwit the fish; that it should be the perfect simulacrum of insect the fish will eat. I will readily admit that I am incapable of such guile, just as I believe fish are. A fish will eat when it is hungry and the opportunity presents itself; anything else is excess. The effort to produce the fly supposedly capable of tricking the fish is still beautiful. The beauty of the place, of the act and of the bargain with nature deserves that effort; one should not complain.

Finding the shape of the world and the clefts in it that accommodate us requires walking through it. I never appreciated great music, or ceramics, or photographs until I tried my hardest and failed miserably at surpassing them. Our failures not only make us better appreciate our own strengths, but also the strengths of others. Such is the case when even the most hopelessly beautiful fly falls into the water beside the true form that inspired it.

To me, tying a fly is the rare instance when I know what I want and every incremental step of getting there — and yet, I’m still captivated by the shape as it takes form. The day unfolds before you. The sunset is inevitable. But its certainty does nothing to diminish its beauty. We wait; it arrives. The coolness of the dark following the fading of the light touches our faces.

Why not revel in it?