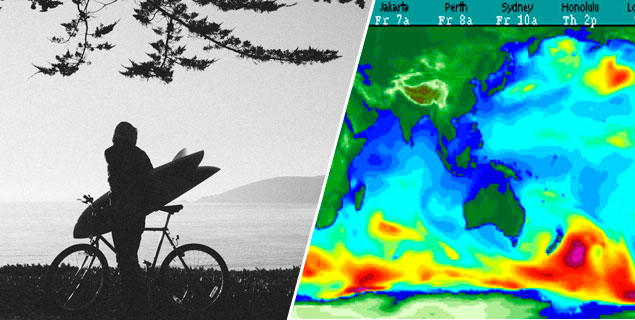

How do you prefer to do your spot check? Photo (L): Jean Paul Molyneux

It doesn’t seem possible that seventeen years have passed since that day when I was busy trying to work out whether a low pressure about 200 miles south of Cape Farewell, Greenland, was going to produce any surf for the north coast of Spain. I was in Plymouth, England, working on my PhD, but was just about to sneak down to Spain for a few ‘practicals’ at Meñakoz. A call from Professor Malcolm Findlay broke my concentration. Malcolm had a guy called Alex on the line – something about an article on oceanography he wanted to run for a new surf mag called the Surfer’s Path.

I was very cynical at first; I thought the UK didn’t really need another surfing mag. However, I went along with it and wrote the story, something about refraction. It was only supposed to be one article, but I took the liberty of stating that it was going to be “the first of a short series,” not holding the slightest hope that Alex would want me to write any more. A few years later, I had written enough articles to base a book on them: Surf Science: an Introduction to Waves for Surfing, now in its third edition. Seventeen years and over 100 articles later, I still haven’t run out of things to say, but unfortunately the Surfer’s Path is no more.

So what has changed since I wrote that first article? Certainly, surf science and surf forecasting has come a long way. But does that mean our overall surfing experience has improved? Are we now all surfing better waves and having more fun in the water? Or is all that new information swamping us and making us more stressed? Will we all soon need to be treated for IOSD*?

One thing that has changed radically is the quantity and availability of swell-forecasting information. The amount and depth of information has increased dramatically thanks to computing power being available to efficiently run huge atmospheric and oceanographic models like the Global Forecasting System (GFS) and the WaveWatch III (WW3). Also, the availability of that information has increased from practically zero to almost universal, partly due to U.S. federal law which allows certain data generated by government institutions to be freely available to the public. Tens, if not hundreds, of websites around the world now download, via the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), wave and wind forecasts, which they then put into punter-friendly graphical formats, several times a day.

A couple of decades ago, the internet was used by a tiny fraction of the people using it today, and swell-forecasting websites were practically non-existent. Resources were scarce. If you were lucky, you could obtain fax-type isobar charts, from which you would have to guess the size, arrival time and quality of a swell. These charts were like gold-dust, and even if you were able to get hold of them, you needed to be a wave-forecasting guru to interpret them well. Nowadays, we can pull out our smartphone at any time, night or day, bring up a surf-forecasting website and instantly access the predicted height, period and direction of the swell at thousands of spots around the globe.

Interestingly, since the GFS and WW3 data became globally available, the biggest explosion has been in the number of websites using that data and in the number of people accessing them, but the accuracy of the models themselves, at least from a surfing point of view, has advanced relatively little. The people at NOAA have made available higher-resolution “nested-grid” models and swell-component breakdowns but little else. One thing that still remains a huge challenge, for example, is to bridge the gap between the deep-water outputs of the model and the surf we see at our local spots. This is where local knowledge and experience still count for a great deal. Fortunately, as I’ll get onto in a minute, many people are starting to better understand the effects of local bathymetry and are becoming more aware of the nuances of their own local spots.

A consequence of this massive increase in information availability is that we not only are able to constantly stay up to date with the forecast for our local spot, but we automatically know what is happening at other spots around the world.

This has altered the lives of the top elite big-wave surfers more than the rest of us. Now, thanks to modern forecasting, it is possible to know where the next 20-foot swell is going to hit anywhere on the globe and, thanks to modern air travel, get there from any other point on the globe in time to paddle out before the first sets arrive.

But it can also alter the lives of ‘normal’ surfers. It can get us surfing better waves on a regular basis and not wasting time going to the wrong spots. With modern swell forecasts we can almost guarantee that we are making the right decision, filling up a surf trip with surfing, not wasting time waiting or driving around in circles.

That’s the positive side. But what if the surf just didn’t materialize or the conditions unexpectedly changed? Twenty years ago, you might have just shrugged it off, knowing that you did your best, but in the end it’s the ocean that makes the final call. You would have done your best to enjoy the situation you were in.

Nowadays, however, you might start looking at the forecasts and see epic surf somewhere else, or back home. This might make you frustrated, wishing you were somewhere else, taking you out of the moment and stopping you from enjoying the situation you are in.

And what if you were a big-wave surfer but didn’t happen to have a six-figure sponsorship to pay for all that swell-chasing? Or perhaps, as someone who enjoys surfing on unspoiled natural coastlines, you felt that traveling halfway around the world for one swell was just too environmentally hypocritical.

*Information Overload Stress Disorder