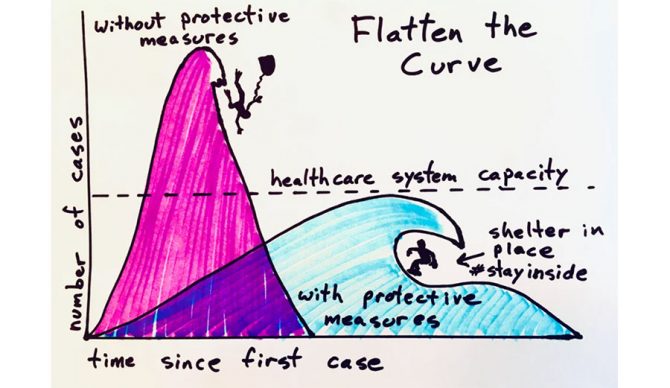

Reddit user Darth_Voter created the surfers’ version of the flatten the curve diagram. Image: Reddit/Darth_Voter

Would so many surfers still object to surf bans if they knew not riding waves would help flatten the curve? The second half of that question is really the crux of an argument infuriating anybody anxious to get waves in the parts of California where it’s banned. It’s the footing surfers stand on when they argue surf bans are unnecessary, irrational, or a blatant exercise in tyranny: “surfing is social distancing” or simply, “surfing doesn’t risk spread.”

But the only people who can truly surf under the state’s stay-at-home order are those who can step out their front door and be content to catch waves within walking or biking distance. And unfortunately, if you’re going to let one person do it, you’re going to have to let them all do it. That’s because the boundaries of stay-at-home mandates don’t just cover asking people to keep a minimum six-foot distance in the water or making sure they don’t mingle in parking lots or congregate on the beach.

Social distancing doesn’t start at your destination, it involves every step outside your front door. So closing off the destination itself is a major tool in containing spread. Driving is an infection risk — something most Californians would have to do to surf or just spend a day at the beach — creating extra touch points, trips to gas stations, and roadside stops along the way. This is why it’s not just surfing that’s been singled out, as we’ve seen, but also many destination-specific activities like camping, hiking, and even shutting down California’s annual migration of aspiring Instagram influencers to the seasonal poppy blooms in Antelope Valley. In the country’s most populous state, with the second-largest land area in the United States, curbing driving habits and limiting every individual’s possible spread radius hinges on keeping people in their neighborhoods. Whether a drive to the beach takes five minutes or 30, 40 million people casually moving around California would add up to a lot of extra trips to the gas pump really quick.

So here’s where the good news comes in: Evidence suggests that California’s stay-at-home order is working, and Governor Gavin Newsom said Wednesday the Golden State is, in fact, flattening the curve.

NEW: CA has 35,396 confirmed positive cases of #COVID19.

3,357 of those cases are in our hospitals. 1,219 of those cases are in the ICU.

CA is flattening the curve–but only if we continue to take this seriously. Stay home. And practice physical distancing.#StayHomeSaveLives

— Gavin Newsom (@GavinNewsom) April 22, 2020

Nearing the end of March, when beach closures in places like San Diego and Los Angeles County (California’s two most populous counties) were relatively fresh, the state’s case count was doubling every three days. It was feared that California was keeping pace with New York as one of the world’s epicenters for the virus, but by April 9, that case rate had slowed to doubling every week, according to Business Insider. The same publication reported this week that when compared to data of America’s other hotspot states — New York, New Jersey, Florida, Louisiana, Michigan, Illinois, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania — California has maintained the lowest rate of cases per million residents. And it’s not even close. California’s tested more of its citizens (by a wide margin) than every state but New York, and despite having the nation’s largest population, it was the only one on that hotspot list with fewer than 1,000 cases per million residents as of April 19.

By comparison, Illinois, Michigan, and Pennsylvania have roughly four million fewer residents than California combined. They’d also all combined to test roughly the same number of people as California has (approximately 450,000), but each of the four state’s total confirmed case counts sit at around 35,000 people respectively, as of Wednesday. Each of those three states has a case rate per million roughly three to four times higher than the Golden State, while New York’s and New Jersey’s numbers all exist in their own stratosphere. And even though studies from USC and Stanford University suggest coronavirus infections in California could be far higher than we know, the state is still seeing a significantly lower average of positive results within its tested population when compared to the rest of the country.

“Different parts of the country are seeing different levels of COVID-19 activity,” the CDC says. “The United States nationally is in the acceleration phase of the pandemic. The duration and severity of each pandemic phase can vary depending on the characteristics of the virus and the public health response.”

What’s the one indisputable difference between California’s handling of the crisis during this phase and not just those other eight states, but the rest of the nation entirely? It was the first place to enact an official stay-at-home order and the first to start restricting or limiting access to at-risk public spaces. For a place with so much to do outdoors and the weather to enjoy it this time of year, closing off specific parks, hiking trails, and beaches has been scrutinized as extreme but likely essential to mitigating spread in the way it has.

Oddly, acting on the side of caution to the point it first appears irrational is a common thread in parts of the world where the spread of coronavirus has been managed best. Not a fun observation, but one that’s been tough to ignore if you’re looking for a barometer of success in keeping humans healthy. Newsom enacted the order on March 19, two days ahead of the next two states to follow — Illinois and New Jersey — and almost two full weeks ahead of places like Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Florida. In hindsight, those days have proven critical.

During the pandemic, citizens have been encouraged to get outside and exercise for their mental and physical wellbeing, so long as those things don’t require a destination where people can gather or can’t travel by foot. The data is starting to show now, a month later, that it’s all working for California. Meanwhile, Santa Cruz’s beach closures have been lifted and San Clemente has voted to lift its beach closures soon too, all with no end date declared for a shelter in place policy. So if you can jump on a bike and surf in your hometown where it’s no longer banned, consider yourself lucky. But be prepared for the wave of out-of-towners who, while not breaking now-infamous surf bans, are working outside the boundaries of the state’s stay at home order by packing into a car and driving to the beach.

Nobody actually knows whether or not it’s too soon to roll the dice on relaxing those restrictions, and nobody actually knows definitively how much surf bans contributed to California flattening the curve to this point. We do know they were enacted in the two counties with the most people and the highest regular traffic on beaches. But these are things surfers will keep arguing about in comment sections until bans are lifted everywhere. The good news, I suppose, is that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel and evidence that what we’re doing is working. That puts us on the path back to doing the things we love and miss.