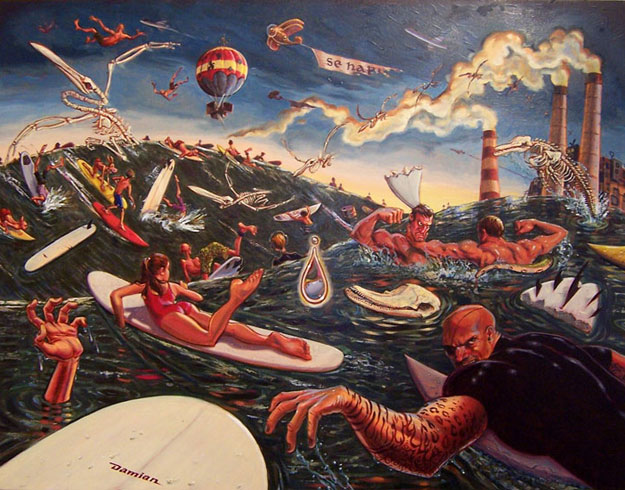

“You might be tied to the “grommet pole” in the car park, force-fed booze, stripped, smeared with excrement, whipped with leashes and left overnight.” Art: Damian Fulton

On a beautifully hot Saturday in August, 2012, at the Huntington Beach pier, huge crowds flocked onto the 1,850-foot pier for the annual Huck Finn fishing derby. Several hundred participants had signed up for the Becky Thatcher-Huck Finn costume contest. Among them was seven-year-old Gracie Veith, who with her dad, had set up her fishing pole and, like many that day, was dangling her line over the edge waiting for a bite. What Gracie didn’t realize, however, was that the tug on her line wasn’t a fish, but an angry surfer far below yanking on her line, pulling her pole and reel into the water. Observers were startled to see scores of surfers hurling profane insults at the lines of people fishing. A bystander saw at least one heavy lead sinker aimed down at an obnoxious surfer. It was not apparent that any citations were issued, but some angered witnesses to the surfer-angler confrontations wondered why the HB lifeguards had not temporarily black-balled the surf next to the pier making this zone off-limits for the day.

Let’s look at exactly how this seemingly small incident—one of many occurring through the years at this and other public piers near popular surf breaks—got out of hand. We know how our sport often carries spiritual weight. The hundreds of coastal piers along our shores are, after all, cultural constructs intruding into the natural domain of the sea with the obvious function of letting people get near the water while remaining dry. California alone has more than 60 piers, and they’re usually dotted with bars, beachwear shops, restaurants, benches, bait kiosks, and those coin-operated, moon-faced lookout telescopes. But surfers nearby, let’s be honest, often regard the surf as their sacred territory and regard the secular world of pier life as an intrusion. At HB, local wave riders use the rip current near the pier to paddle out, often snagging their wetsuits on anglers’ lines that have drifted into the rip–a situation that can rapidly turn ugly. Folks fishing from the pier can’t understand why surfers (labeled “Surf Nazis”) need to get so dangerously close to the pilings with miles of ocean open to them. Meanwhile, surfers don’t see why fishing can’t be confined to the end of the pier. Sounds a lot like the days of tussles between surfers and fishermen at Sebastian Inlet–Florida’s east coast surfing mecca where epithets and lead sinkers were hurled between warring factions. In the absence of any lasting truce, the surf/turf wars trail us like the dark shadow of a shark.

Sure, surfing’s sacred origins are well-known to us today, a time when much of pre-contact Hawaiian life was governed by the Kapu system of laws and tabus; a time when kahunas of respected lineage would launch special kites into the air above the Diamond Head Kuemani Heiau (temple for encouraging big surf) signaling to islanders that it was time to break from their tasks and gather oceanside for he’e nalu (surfing); a time when riding waves was seen as a communal experience swathed in special prayers and chants, the kahuna lashing the water with kelp or pohuehue wands to stir up kahiki; a time when no masculine hegemony prevented women and children from surfing though there were rigid class distinctions; and a time when surfing might even be called off if conditions were deemed too dangerous, a sign that the gods themselves were surfing.

Today, our “kahunas” include NOAA meteorologists, and oracular surf-cams and surfcasters, to which we show obeisance (my favorite is “Buddha” at Surfguru.com), and our Oakley-wrapped contest judges enthroned on their waterside scaffolds. Our “temples” are the Volcom, Quiksilver, Billabong, Hurley, O’Neill, Rip Curl, Sanuk, and Dakine festival tents, all testifying to the secularization, the commercialism of our sport, the wedding of the profane to the sacred. Perhaps nowhere is the blending of these sacred/profane domains more beautifully illustrated than in surfing’s poignant and joyous ritual of the memorial paddle-out, the ho’okupu. Who among us has ever attended one of these ceremonies without coming close to tears? These rituals elegantly combine what anthropologist Arnold van Gennep years ago called “rites of passage” and “rites of intensification.”

Take the paddle-out honoring the famed 800-pound Hawaiian vocalist Israel “Iz” Kamakawiwo’ole who died of respiratory failure in June, 1997. He was 37. After his body lay in state at the capitol in Honolulu, the first musician in Hawaii to be honored this way, 10,000 people attended his funeral and huge crowds made their way up the west coast of Oahu to Makaha where “Iz” formed his first band. Hundreds paddled out on boards, rafts, and flower-bedecked traditional Polynesian outriggers to chant, make offerings, and scatter his ashes. Like paddle-outs everywhere, the death and life of the deceased is marked as a “passage,” while the solidarity and community of mourners is “intensified.”