Dan Malloy (C) with friends and fellow travelers Kellen Keene (L) and Kanoa Zimmerman (R). Photo: Patagonia

When we spoke on the phone, Dan Malloy sounded like he was in the middle of a rugged stretch of central Californian coastline. He very well might have been. Truth be told, he sort of always sounds like he is in the middle of a rugged stretch of central California coastline. It’s what we’ve come to expect with the surfer-nomad-farmer-rancher.

Dan and his brothers have been at the forefront of Ventura-based Patagonia’s recent lifestyle initiative, one that encourages people from all walks to not only embrace outdoor activity, but to educate themselves on environmental issues and employ environmentally-conscious practices in their day-to-day as well. From friends and family here in California to the city-minded folk who frequent Patagonia’s surf outpost on Bowery in New York City’s NoHo to locals fighting against damming in Chile, the clothing company has repositioned itself as far more than a mere clothing company.

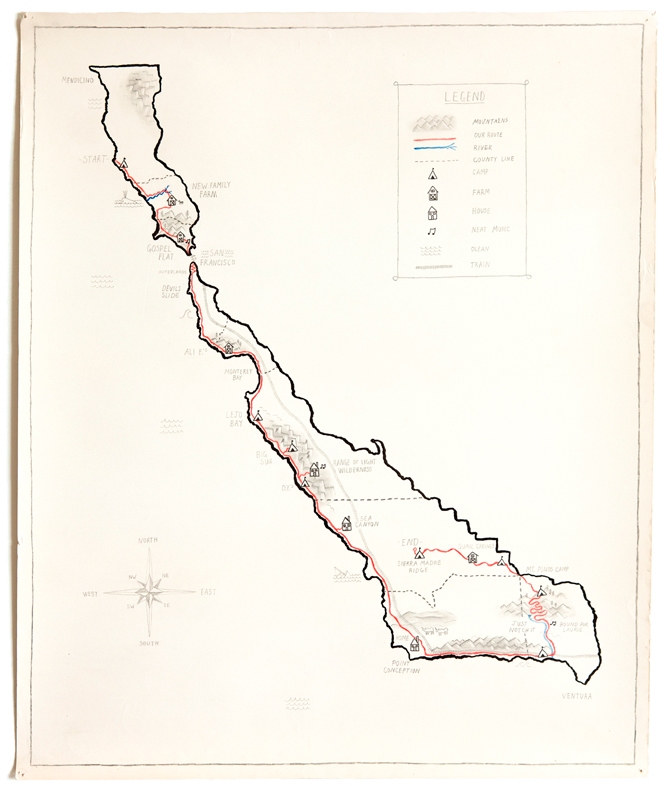

And while Dan is involved in a number of different projects — and even has his own Stoke Grove Farm — his most recent was a personal one that he had long wanted to do. Slow Is Fast is a new travel book that if you haven’t read, you really should. Actually, it’s much less of a “read” and more of an experience that invokes the ol’ tattered National Geographics you found in your grandfather’s den as a kid. The pages offer a lens that is less RED camera and more 35mm — the way it should be, ’cause life is a little grainy at times — and presents them as snapshots to accompany short interviews with the people who make up the frontier that Dan, Kellen Keene, and Kanoa Zimmerman explored by bike.

Anyway, I recently caught up with Dan to talk about the places he saw, the people he met, and how his own perspective of surf travel has changed over the years.

Michael Woodsmall: I want to jump in and, first and foremost, talk about the bigger picture. Over the years, you’ve been able to establish yourself as a storyteller, especially in the way of films. When you go into a project like this, especially with a project as personal as one involving the California coastline, what are your intentions? Is this simply an opportunity for adventure, and what comes will come, or is there a larger purpose motivating you and your crew?

Dan Malloy: For me, most of the trips I’ve done in the past, it’s an excuse to figure out a way to be around the people who really interest me, and go to the places I’m dying to go. If I can figure out a way to tell a neat story about them or the place, then I might get to keep doing it. [Laughs.] I don’t feel that that is too bad of an ulterior motive.

However, this time, there were so many different things that brought me to want to go do this. The main thing is that I have already done one short bike trip before and it was just a blast — you’re moving all day long, surfing a bunch, and hanging around good people. But so many trips these days are dictated by photos. I feel like all the real neat stories we used to read and hear about, there were only a few photos taken and that was more as artifacts and evidence. There weren’t a thousand pictures being taken during the day; to me that seems a little bit crazy. So this trip we were like, “let’s go on a super fun trip, and take some photos and video, but not let that completely trample the entire thing.”

And there was more, like farming. From the things I wanted to learn, you’re going to learn more about your area if you do it close to home, and California is the climate that I’m in. Ultimately, it was also a reaction to traveling so much and wanting to — still needing to get that fix, but I didn’t want to get on planes.

Then when did the people — people other than yourself and Kellen and Kanoa — become such an integral part?

From the outset, it was about the people that I had met in the past and I knew were there. I also knew it was really hard to actually go investigate, meet with these people, and tell their story even close to correctly. You’re never going to tell it perfectly, especially when you’re passing through in a day.

The other side of it is I’m really tired of telling my own story, which is beating a dead horse at this point as far as surf media goes. It is the same ol’ thing: we go on these crazy trips halfway around the world to these unbelievable cultures and you come home with 18 shots of us doing tricks, and then one potent shot of the culture — and that’s the story.

This trip was about the people we were hanging with. Pro surfers aren’t that interesting — there are a couple interesting ones left, but most of the time they simply are not that interesting. Don’t get me wrong, I love that shit: I look at the magazines and watch the videos. And in this day and age for me, my surfing is far from cutting edge so the last thing I want to do is focus on my surfing or myself.

Photo: Patagonia

If you knew that it was going to be “really hard,” then what sort of tact or strategy did you take into the trip?

So the question is: if we go after what is interesting to me, and don’t overdo it, is it interesting to other people? This was definitely an independent project when it started out and I was explaining to people what I was trying to do and they didn’t understand, but we pared down the stories and made it as accessible as possible. Thus far, it is being received better than planned.

This one was really fun. First off, the thing that gave us the real inspiration to see it through — well, not “inspiration,” I don’t know what that means anymore — but what kept the energy going was that we asked a lot of these people to allow us to spend a couple days to a week with them. And we respected these people a ton. Therefore, we really felt responsible to tell their story well and correctly. Each interview was at least two hours long. How do you edit that without screwing up what they said? There is this little room in my house that has nothing in yet. During the editing process, we had photos of the trip plastered on the walls. Over the course of three months, we would go through and figure out the order. Sometimes if your favorite photo didn’t add to the story you would have to let it go. That was really hard as well.

Even though there weren’t a lot of expectations behind it, we spent a ton of time on the concept, from the words to the photos. That book was a big thank you to the people we stayed with.

Seems like the thank you paid off…

I’m super excited that it worked out, and it was my first shot at building a crew and making a project — for me, that it didn’t fall completely flat, is really exciting. We traveled in a way that I felt was pretty darn respectful of the places we were going and people we were with. I’ve always tried really hard to do that, but when you go on these quick trips, it’s not always possible to really take the time to both enter and leave a space respectfully, without leaving anything or anybody hanging.

Sometimes, I’ve felt uncomfortable about the way I’ve traveled, but this was a completely different way to do it for me — and we were still able to tell a story. Not to be in as big of a rush to get the content we needed. These days, with web and everything, it’s all about content. If you get content, you’re golden. It’s hard not to let that overwhelm what you’re up to.

Through Jeff Canham, the designer, and everyone else, I was pretty darn happy with how it came out. The first run we did was 1,000, and I was worried we were going to have trouble getting rid of those. But we did. And we’re now its fifth printing.

It’s been interesting to watch it — it doesn’t really hit the nail on the head with the surfing industry ‘cause it’s not cutting edge surf — it’s not big wave or high performance or competitive surfing. There’s a part of the deal where it misses there, but that’s okay. That wasn’t why we made it.

You’re hesitant to use “inspiration,” but what, in the end, inspired the format you published the book in?

There was a book by Margaret Kilgallen, In the Sweet Bye and Bye, that influenced the process. It was that and inspiration from Japanese books that Kanoa had. We wanted to make something super simple, as simple as it gets. I’ve had a few books like that in my life, something you could carry with you wherever you went.

What has this entire experience done for you? What are your takeaways? What are the highlights?

Finishing it was pretty surprising. [Laughs.]

Let’s see, the most surprising thing for me would be… I suppose I’ve been learning that of all things, surfing in moderation is actually a pretty healthy balance. On that trip, we were only surfing so much, ‘cause we were working a bunch, and when you’re riding your bikes you’re not always going to be at the best spot or be at a spot that’s surfable at all for a few day. That moderation of not surfing for a few days, and working really hard, and surfing every four or five days and only finding good surf maybe two or three days out of a two month trip added a whole new element to my surfing experience. I’ve actually been finding that now that I’m not competing anymore and not in the water every single day, that I enjoy it more after I’ve been working hard on something, whether it’s a project or outside on our place out here.

It gets a little weird and possessive when you’re surfing everyday — who is out at what spot spot and all this stuff. When you fill your life with other things and go down to the beach to blow off steam it doesn’t quite seem like such a great deal. It’s not something to take too seriously.

The road less traveled. Photo: Patagonia

If you want to see what Dan is talking about, read the book, available for $30 from Patagonia’s online store.