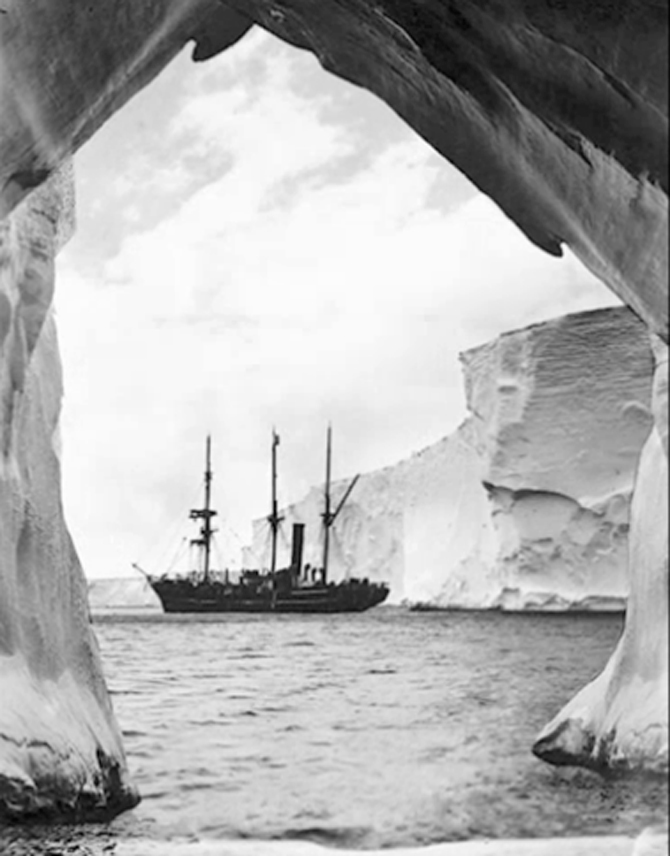

Screenshot: Frank Hanley via National Geographic

“Just have one more try — it’s dead easy to die, it’s the keeping-on-living that’s hard.” – Robert Service

A 95-mile trek across Antarctic ice. Hungry. Fighting not only dire circumstances, but deadly crevasses. Alone. These are not conditions you overcome. These are not conditions you survive. These are not conditions you come back from.

But Australian Douglas Mawson chose a different ending to his story, one of strength and perseverance, struggle and sacrifice — one you likely have never heard. Until now.

The explorer and his story recently received its due when it featured in National Geographic and presented for NG Live! with none other than award-winning writer and adventurer David Roberts narrating the account.

Robert Falcon Scott, Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundson… these are names that carry the hefty weight of widespread fame for their feats. Yet Mawson, whose contributions are as sizable and significant — if not more so — than his contemporaries, is relatively forgotten in the way of history books and popular retellings. Why? There are many potential reasons, but the logical one would be that, unlike his contemporaries, Mawson wasn’t interested in the poles. Amundson and Scott’s race to the poles (and Scott arriving a month after Amundson, but dying with his companions) made for front page news and ensured legacies. Mawson sought something different; the Aussie sought a comprehensive survey of the land. Rather than records and headlines, he was driven by a raw thirst for information.

So, along with an expedition young explorers, Mawson set off for Antarctica in 1911. Accompanying him was photographer Frank Hurley, who was able to document stretches of the trip. What led Mawson to the southernmost continent was a radical new plan on how to approach the unexplored landmass. Thus he arrived and anchored at Commonwealth Bay, the only inlet that would provide an accessible entry point.

Screenshot: Frank Hanley via National Geographic

What Mawson didn’t know at the time was that the fierce and continuous winds he and the ship were experiencing at the time were not random but the norm there. In fact, since then it has been documented as the windiest place in world at sea level. As might be expected, this lent to a tremendous stress and hampered any easy access of the continent. But they made it ashore, though the winds would still plague them. Hurley would later recall that 80 mile per hour winds manageable; it was the 100 mile per hour winds that floored you.

Screenshot: Frank Hanley via National Geographic

Anyway, with the conditions being what they were, the crew needed to wait for winter to pass Needless to say, winter there was unlike any that the crew had experienced before. The front door to the base literally snowed in…

Screenshot: Frank Hanley via National Geograph

…they had to go through the roof to get outside.

Screenshot: Frank Hanley via National Geographic

Once spring and then summer came, the crew was ready. Mawson went about splitting the 18 men into three-man teams. Therefore, there were six different teams. According to Roberts, “the simple point was to discover new land and go every direction possible.” Most of these teams were manhauling, though the most ambitious group would take a sled dogs to help with the sledge. This ambitious group was headed 350 miles to southeast to link up with land Scott had discovered in Ross Sea. And it was comprised of: Mawson; Xavier Mertz, 28-year-old lawyer from Switzerland and the Swiss ski jump champion; and Belgrave Ninnis, 26-year-old British soldier who was nicknamed “Cherub” for his youthful appearance.

Unfortunately no photographs survived the three-man expedition led by Mawson, but Hurley took other shots that exemplify the obstacles that stood in their way.

Screenshot: Frank Hanley via National Geographic

The trials and tribulations must not be undersold. Roberts writes as much in an accompanying piece for National Geographic:

Mawson heard the faint whine of a dog behind him. It must be, he thought, one of the six huskies pulling the rear sledge. But then Mertz, who had been scouting ahead on skis all morning, stopped and turned in his tracks. Mawson saw his look of alarm. He turned and looked back. The featureless plateau of snow and ice stretched into the distance, marked only by the tracks Mawson’s sledge had left. Where was the other sledge?

Mawson rushed on foot back along the tracks. Suddenly he came to the edge of a gaping hole in the surface, 11 feet wide. On the far side, two separate sledge tracks led up to the hole; on the near side, only one led away.

This incident would have the expedition one-man down, with Ninnis not surviving the fall. Soon thereafter, there would be no more dogs, leaving the surviving two with 100 miles to walk. And soon after that, there would be no more companions at all. Exhausted from the journey, Mertz went into a delusion forcing Mawson to subdue him. Mertz would not get back up. At this point, Mawson saw no return.

I have no hope of making it back alive.

What ultimately pushed him Mawson on was an incessant need to cache his and Mertz’s diaries somewhere that people would find them. He lay his faith in a trust in providence as well as the aforementioned verse from Robert Service: “Just have one more try — it’s dead easy to die, it’s the keeping-on-living that’s hard.”

From losing the soles of his feet to falling into a crevasse himself, Mawson overcame and survived conditions you do not come back from. The worst part? When he finally did return to the base, Mawson missed the relief ship by five hours, condeming he and the seven men there to search for him to another winter. Tough luck, to say the least. He would, however, eventually get back and successfully pass along the information he and his comrades had collected.

And just because the rest of the world has more or less forgotten this epic tale, he is held not only in high regard but as a national hero in his home country of Australia, as Roberts goes on to explain:

When Mawson finally reached Australia in February 1914, he was greeted as a national hero and knighted by King George V. He spent the rest of his career as a professor at the University of Adelaide. Although he would lead two more Antarctic expeditions, his life’s work became the production of 96 published reports that embodied the scientific results of the AAE.

When Mawson died in 1958, all Australia mourned its greatest explorer.

Screenshot: Frank Hanley via National Geographic

If you have a half hour, definitely worth watching the entirety of this NG Live! and hearing all the anecdotes that contribute to such a legendary but lost lore.

For the entire, original story as told by David Roberts, head over to National Geographic. And don’t forget to check out photographer Frank Hurley’s visual account of the expedition. Finally, be sure to have a look at the historic photographs from The Race to the South Pole between Roald Amundson and the less fortunate Robert Falcon Scott.