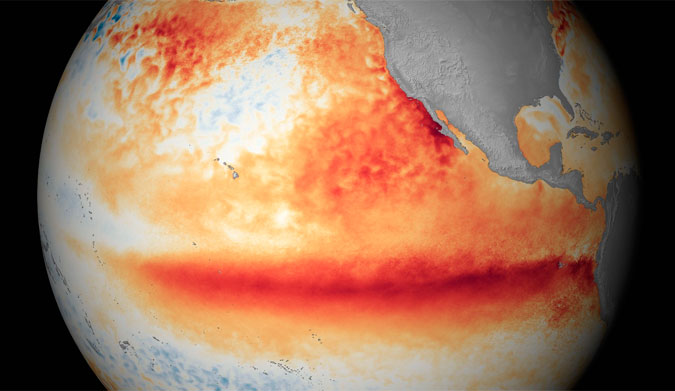

All signs point to the most powerful El Nino event ever. Image: NOAA

If all the reports are correct, we’re in for a hell of an El Niño event this year. It’s already affecting things–Hurricane Patricia was supercharged by the fluctuating water temperatures, October was the hottest month in 136 years of data, and the drought in Indonesia played a pretty big part in the massive forest fires. According to new data, though, El Niño is just warming up.

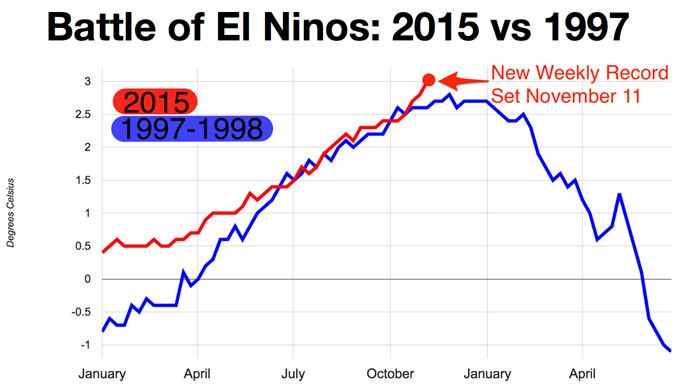

The El Niño event in the winter of 1997-1998 is widely considered to be the most powerful. Sustained temperatures over a three month span were higher than ever before. This one, however, is shaping up to be worse. According to Bloomberg and new data from NOAA, October was more than just the hottest month on record. It was “the biggest departure from normal for any month in the last 136 years.” It was such a departure, in fact, that even if November and December stay on the low end of the thermometer, 2015 will be the hottest year on record. Kind of scary, isn’t it?

“We are in uncharted territory,” wrote Tom Randall for Bloomberg. “These new milestones follow the hottest summer on record, the hottest 12 months on record, the hottest calendar year on record (2014), and the hottest decade on record. Thirteen of the 14 hottest years have come in the 21st century, and it’s only the beginning.”

The Earth’s warming climate, recorded in monthly measurements from land and sea dating back to 1880. Temperatures are displayed in degrees above or below the 20th century average.

The World Meteorological Organization fully expects it to get much, much worse. If we’re using past El Niño years as a measuring stick, the peak of the event generally winds up being sometime between October and January–and this year, El Niño is only gaining steam, and it’s doing so at an alarming rate.

“Our planet has altered dramatically because of climate change,” said the WMO Secretary General, Michel Jarraud. “The general trend towards a warmer global ocean, the loss of Arctic sea ice and of over a million square kilometers of summer snow cover in the northern hemisphere. So this naturally occurring El Niño event and human-induced climate change may interact and modify each other in ways which we have never before experienced.”

So what exactly happens in an El Niño year? It’s a little complicated. During a normal winter, winds blow from South America’s western coastline towards Australia. This pushes the warm surface water away from the coastline, and the colder water below it rises to take its place. The ocean plays a vital role in regulating the temperature of our planet, and these patterns are a big part of that.

In an El Niño year, however, those winds change dramatically. The stronger the event, the more effect on the water temperature. Sometimes, the winds not only weaken, but reverse direction all together, forcing the warmer water back towards the coastline instead of out towards to the open ocean. This change in ocean convection affects everything from global wind patterns and temperature to currents.

Although scientists have been using events from past years to try and predict what might happen this year, a few things are making that difficult. “Even before the onset of El Niño,” Jarraud explained, “global average surface temperatures had reached new records. El Niño is turning up the heat even further.”

It seems the only thing we can do is wait and watch–and with any luck, we’ll be spared from any more super-charged natural disasters and score great waves, instead.