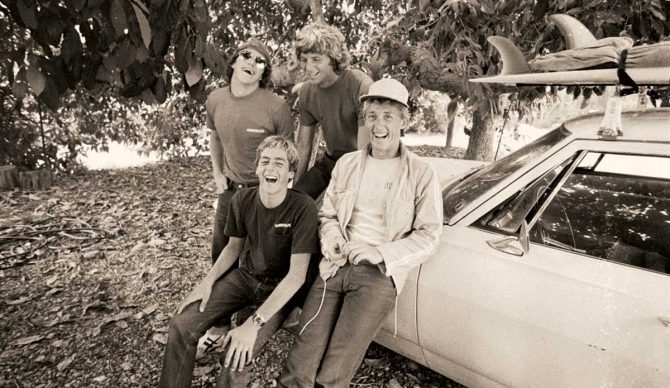

Clockwise from lower left: Tom Curren, Matt George, Sam George, and John Witzig’s friend, Neil. Photo: John Witzig

Editor’s Note: “Scrapbook” is a limited series from The Inertia’s Sam George, in which the longtime surf scribe draws from a vast trove of personal stories and photos to present a collection of entertaining tales that, while spanning decades of his surfing life, are easily relatable to any of us who’ve joined him in that pursuit.

For some inexplicable reason, in 1968 the package store on Oahu’s Pearl Harbor Naval Base carried Australian surf magazines. This is why I began my surfing journey, not only poring over any issue of the American mags I could lay my hands on, but steeped in Aussie imagery and lore, absorbing exotic content from titles like Surf and Surfing World. Introduced, most significantly, to the wider work of journalist/photographer John Witzig.

I knew of John Witzig, of course, having previously puzzled over his 1967 SURFER magazine feature “We’re Tops Now,” a deliberately provocative assertion that Australian surfers had finally shrugged off their thrall of California surf culture, and now topped the class in the new high-performance school. More impactful, even, were his remarkable photos of Nat Young and Bob McTavish proving that point on an incredible day at Honolua Bay in December of 1967, where, on their short, wide vee-bottomed “plastic machines,” they introduced us to the future.

Witzig’s steady gaze brought that quantum leap to life — the guy was one of surfing’s major influencers, long before the term was invented. Yet for me it wasn’t his provocations or action photography that shaped a nascent awareness of what it meant to be a surfer, but his intimate photojournalism, eloquently capturing what came to be known as Australia’s late-1960s “Country Soul” era. In contrast to American surf magazines, at times depicting the sport as one big “Hang 10” surfwear ad, Witzig portrayed surfers like Nat, McTavish, Wayne Lynch and Ted Spencer as leading figures in a counter-culture, whose choice of lifestyles wasn’t merely a modern emulation of the Waikiki beachboy, but one of more thoughtful intention. At least that’s how my over-imaginative, 12-year-old mind interpreted it.

So, imagine my surprise and pleasure when, on a chilly evening in 1980, my brother Matt, Tommy Curren and I surreptitiously slid into a super-cool Montecito backyard BBQ (drafting off Al Merrick’s legitimate invitation) and found none other than John Witzig sharing a beer with a few of the older, relentlessly bitchin’ Hammonds/Hollister Ranch crew. Undeterred, I resolutely approached John and introduced myself, launching almost immediately into an ingratiation campaign by telling him how much I appreciated his brief tenure as editor at Surf magazine in ’67. “Ancient history,” he laughed, explaining that he was now here researching a story for SURFER, examining, from his antipodal point of view, the contemporary state of California surfing. Adding, in explanation, that he hadn’t been back to the Golden State since visiting 14 years earlier, when, in a run-up to the 1966 World Contest in San Diego, George Greenough, the innovative Montecito scion (and progenitor of the “Shortboard Revolution” Witzig had documented), hosted John and Nat Young up at the notoriously private Hollister Ranch, where Nat prepped for his anticipated duel with David Nuuhiwa in pristine, uncrowded tubes at Rights and Lefts.

“But none of these guys will take me this time,” he complained, pointing a bottle of Corona at the knot of Santa Barbara’s “made men” hanging out over by the sizzling grill, languidly swapping swell stories. Now, I may not have warranted a spot flipping the tri-tip, but with an eye on showing off in front of a legendary character in surf history, sensed an opportunity

“That’s no problem,” I said. “We’ll take you in.”

“You guys?” he asked, considering us with more than a hint of critical assessment — Matt and I were a pretty scruffy pair, and Tommy all of 15 years old. “And just how do you intend to do that?”

“Easy,” I said. “We’ll sneak in on foot. Do it all the time.”

Truthfully, we had done it successfully only once, and even then with mixed results. On this occasion we three, fueled entirely by dreams of empty perfection and a handful of Jolly Ranchers, hiked in from the north, off the Jalama Road, beginning our furtive, seven-mile trek along the Union Pacific railroad tracks at about 2:00 a.m., reaching the beach at Government Point, the distal end of the off-limits Bixby Ranch, just before dawn. There we huddled together in the cold, wrapped in our boardbags like stranded mountaineers in a high-altitude bivouac, waiting for the rising sun to warm the lineup. The waves were small, and the morning offshores too brisk at Gov’s, so following a futile wake-up session we gathered our things and continued our trek south-east to Perkos, the next spot on the Ranch’s fabled itinerary. Much glassier here, and the dream was realized: surfing really fun waves, against a backdrop of glorious, untrammeled California coastline, all by ourselves, all day.

Therein lay the problem. Following our long, physically exhausting day of hiking and surfing, we now had to walk back to the car, an additional eight miles; the Jolly Ranchers had long been sucked down to nothing. No point in describing what our version of the return “Pt. Conception Death March” was like, except to say that although none of us admitted it at the time, we all secretly cherished hopes that we’d get caught by the patrolling ranch guards — at the least we’d get a ride out.

Naturally, I didn’t tell Witzig about this shameful aspect of our adventure, but pressed on, more interested in establishing my bonafides than actually staging a crazy surf mission.

“If you wanted to take the shorter route from the south, we’d have to leave now,” I said. “So that we’d sneak past the gate when the guard’s probably asleep. That is, if you really want to surf the Ranch.”

And then came my second surprise of the night.

“Let’s!” said John Witzig.

I’ll let him take up the next part of this saga, with excerpts from the feature he eventually published in SURFER:

“By 1 a.m., we [John was traveling with a buddy named Neil] had borrowed food and clothes, and packs to stuff them in. When we got to Gaviota there was no swell. Still, we told each other, remember that time when it looked flat and whatitsname was four feet by dawn? We were undeterred even by a crew who’d already been in by boat and said it was quite flat. They, we figured, were probably Valleys who wouldn’t recognize a wave if they stumbled over it. And so we walked in…”

Stumbled in was more like it, following the awkwardly-spaced railroad tracks all the way up to the bay at Big Drakes, with me self-consciously leading the way like some school kid on a personal field trip with his teacher. But John took it all in stride.

“We thought we were pretty clever as we sneaked past the guard by keeping in the shadow of the inland cutting,” he wrote. “We did it one by one. Good war games. Exciting, even.”

Excitement, yes, and served with a healthy portion of an illicit thrill lacking in much of today’s modern surf experience. Yet when after about an hour-and-a-half of silent trekking we got up past Razorblades, the first spot on the proximal eastern end of the Ranch, we couldn’t kid ourselves any longer. It was flat. Dead, mill-pool flat. Despite trying to put the best face on things, my appraisal of the conditions was understandably bleak. John, however, turned out to be the best of sports.

“So we sat down at the northern end of that trestle bridge,” continued his account of our ill-fated Ranch trip. “And we had an early breakfast of bananas and some disgusting cake that tasted terrific, and we passed the water around. The spirit of camaraderie that accompanied us thus far didn’t desert now.”

Though I’m pretty sure it was Tommy who first whispered it, I can’t recall whether it was me or Matt who officially presented a startling option to John and Neil.

“Sam or Matt had an idea,” John remembered. “There would almost certainly be waves at Jalama. If we walked back now (there really being no reason to go on), we could drive to Jalama and be there about dawn. And since going back to Santa Barbara without having got in the water would be an admission of defeat of the worst kind, it was agreed.”

We hustled back to the cars, brazenly tromping past the guard gate this time, and made the 30-mile drive from Gaviota up to Jalama in record time, the winding, crudely-paved Jalama Road out to the coast particularly memorable for John, who previously had not seen much of California.

“I think it was perhaps the first time that I’ve seen forests of those black-green oaks that remind so much of Spain,” he wrote of the drive west through the undulating foothills. “There had been a lot of rain, but in the early summer the hills were already browning. The contrast between it and the trees is at once subtle and spectacular.”

Anticipation was high as we crested the final hill, took the last turn and got our first look at Jalama’s “Out Front” lineup: two-foot peaks struggled to reach shore in the face of cold, whistling offshore winds. The sun’s first rays, still banking high above the the Santa Ynez range to the east, had not yet settled over the empty lineup. The parking lot was equally empty — much like at the Ranch, everybody else probably knew better. Did I mention how cold it was?

This time I know it was me who spoke what Matt and Tommy were surely thinking.

“Well, look, the sooner we go out, the sooner we can come in,” I said. “That way we can get back to Santa Barbara in time for breakfast.”

Our Aussie mates shared one, quick dubious glance. And then they cried until they laughed.