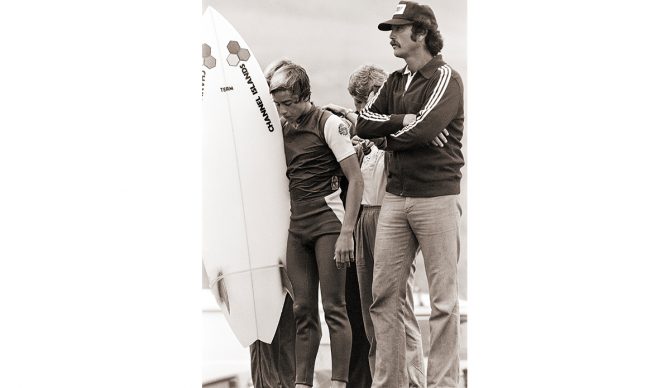

From his pro contest debut, one movement in Curren’s captivating performance at County Line. Photos: Jmmy Metyko, from Shaping Surf History, Rizzoli Books

Editor’s Note: In this exclusive, three-part series, The Inertia’s Sam George looks past the standard profiles and promotion to capture the essence of what has made the great Tom Curren truly a legend in his own time.

PART ONE: SO IT BEGINS

On a soggy, grey, “June Gloomy” October morning in 1980, the cream of the professional surfing world could be found in a grubby Southern California dirt parking lot, trying to keep their feet clean. Located just west of the L.A.-Ventura County line, marking either the end or beginning of Malibu’s stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway (depending on which way you’re traveling), the venerable surf spot known as County Line was on this day inexplicably hosting the United States Pro Invitational surf contest.

The event, having apparently been relocated to this unincorporated outland due to permit snafus that denied organizers access to Malibu’s legendary First Point, was by all accounts considered a come-down, despite the presence of most of the period’s IPS Top-16 competitors, as well as a swarm of ancillary West Coast, Hawaiian and East Coast trialists, all clamoring for attention from under the shade thrown by major-leaguers like world champions Peter Townend, Shaun Tomson, Rabbit Bartholomew, and Island stars Dane Kealoha and Michael Ho. What this eminent collective thought about their participation in the decidedly unglamorous proceedings, with most of the crowd on hand this morning not here to witness world-class performances in County Line’s clean, head-high reef/point surf, but for coffee and breakfast at the Neptune’s Net restaurant and biker bar across the highway, can easily be imagined. Four years after the inception of the modern international pro tour, this was hardly “The Show” the top tier had envisioned.

It was, however, a big deal to the local California competitors, many of whom, motivated by the opportunity to compete against the world’s best without having to buy airline tickets to Hawaii or Australia, would make a fine account for themselves on their home turf. In fact, seven of the final 16 place-getters were Californians, a golden result in what passed for a major Golden State event. In the end, though, only one of those magnificent seven mattered — to the sport’s biggest surf stars, to the media, to competitive surfing history. No, it wasn’t Dean Hollingsworth, J Riddle, Jeff Parker, Dale Hight, Scott Daley, and certainly not Sam George; one-off irritants, none of these six caused the top-ranked pros any lasting apprehension. It was clear to that pantheon, and to everyone else watching from County Line’s dirt parking lot, that none of these surfers would ever threaten the established order, or vie for multiple world titles, or change the sport’s entire performance aesthetic. Let alone someday be recognized as one of the greatest surfers of all time.

Only the seventh California surfer would end up doing all that.

“The crowd favorite was 16-year-old Tom Curren, who came down from his home in Santa Barbara and put on a spectacular show in his first pro contest. Working his way to the top 16 after upsetting Michael Ho in the man-on-man.”

– From “Hot On The Heels,” SURFER magazine, 1980

Up at dawn, our caravan drove down Highway 101 from Santa Barbara: Al Merrick, Tommy, Tommy’s mom and siblings and the whole Channel Island contingent, every car load trying not to look as we passed Rincon, glassy and head-high in an early-season west swell. The Country Line parking lot was already jammed with the contest scaffolding, camera crews, contestants and hangers-on, and so, like untold number of surfers before and since, we parallel-parked along the narrow, coast-side shoulder of PCH, and, risking life and limb, turned sideways and crabbed our way back to the contest site to check in for our respective heats, everyone feeling very important.

But here was the thing about going anywhere with Tommy Curren back then: you were invisible. We all were. Only Tommy, just 16 at the time, would turn those heads, alone amongst us the subject of whispered recognition and implied deference. And not just from local surfers up and down the California coast. Few of the big names here at County Line had ever seen Tommy surf, having only heard tales of the young amateur phenom from way up Rincon way, and they eyed him curiously as we established our CI beachhead.

This slender, modest, seemingly unassuming teenager, the next Big Thing? The contrast with Joey Buran, the existing “California Kid” and the state’s most successful pro competitor (already ranked in the IPS Top 16) couldn’t have been more pronounced. Buran: loud, brash to the point of obnoxious, his surfing performed in a perpetual crouch, approaching each wave as if he was in a batting cage, swinging for the fences. Curren: quiet, not shy, but thoughtful, spending his insights and perspectives sparingly, his surfing preternaturally fluid and precise, reading each wave’s individual movements like musical notes on a chart. For most of the international pros, this would be their first chance to see him in action; to assess expectations.

These expectations were as high as any to have been leveled onto the shoulders of a young amateur surfing champion. But honestly, it wasn’t like anyone predicting greatness was going out on a limb. Tommy’s amateur record would be, to put it mildly, seismic. Complete dominance of a full year of WSA district and invitational events, U.S. Boys titles in 1978 and ’79, 1980 U.S. Junior title, 1980 World Junior title (and two years later the men’s title) — he was already being considered by any of those who happened to see these performances to be America’s best young surfer. And yet, not in the way that other amateur wunderkinds would be touted in the years that followed. Phenomenal talents like pre-teen David Eggers, or young Kelly Slater, or even the great Carissa Moore, whose competitive successes were seen more as a result of a deliberate campaign, with multiple titles inevitable.

In Tommy’s case, the impressive trophy collection weighing down shelves in the Curren’s modest compound on Santa Barbara’s Milpas St. (not on the wrong side of the Southern Pacific tracks, exactly, so much as right on the tracks), told but a portion of his story. As impressive as it was, the garish collection of statuettes failed to reflect the thing that made so many observers, groms and grownups, pros and amateurs alike, sit up and take notice, not only every time Tommy paddled out in a heat, but even when just warming up down the beach. As they did this morning at the U.S. Pro Invitational.

Sixteen-year-old Tommy with shaper/mentor Al Merrick, both obviously very serious about making a big first impression.

It was his presence. Whether riding his tiny Al Merrick-designed tri-plane hull single fins, or, by October of 1980, on one of Al’s highly-refined twin-fins, Tommy always seemed to be floating above it all, in a quiet space of his own. Wearing a jersey or not, his surfing seemed to reflect no determined effort, but instead appeared as if he was simply dancing to that music none of the rest of us could hear.

A true savant? Easy diagnosis…for those who didn’t know him well. Truth is, when in the comfort of close friends and older mentors like Al Merrick, myself and my brother Matt and photographer Jimmy Metyko (especially around Jimmy), Tommy was just a bright, witty kid, with a wicked sense of humor and flair for puns. Could play every drumline and fill on the Who’s “Baba O’Reilly.” Loved green apple Jolly Ranchers. Soaked his booties in Pine-Sol between sessions. Just a kid.

But a kid destined for greatness. Evidence of which was on display this day at the U.S. Pro. That SURFER article was right: Tommy, in his debut performance against the world’s best, was indeed the crowd favorite…to just about everyone but a few of those top seeds. Jimmy Metyko clearly remembers watching eventual winner Rabbit Bartholomew watching Tommy out-surf veteran Michael Ho in a man-on-man matchup, with much more serious intention than he’d spare even for his peers. It would be no coincidence when Rabbit and runner up Shaun Tomson, heretofore single-fin devotees, both switched to twin-fins after witnessing Tommy’s groove on one of Merrick’s. They got their first glimpse of what was coming — and who was coming — at Tommy Curren’s first pro contest, there in the dirt at County Line.

The world’s turn would come next.

In Part II of “The Legend Of Tommy Curren” the young Californian, who, in order to retain amateur status, forfeited not only his ninth-place prize money in this event, but that from his second-place finish (behind Shaun Tomson) in the 1981 Katin Team Challenge, finally turns pro. And the surfing world shifts on its axis…stay tuned.