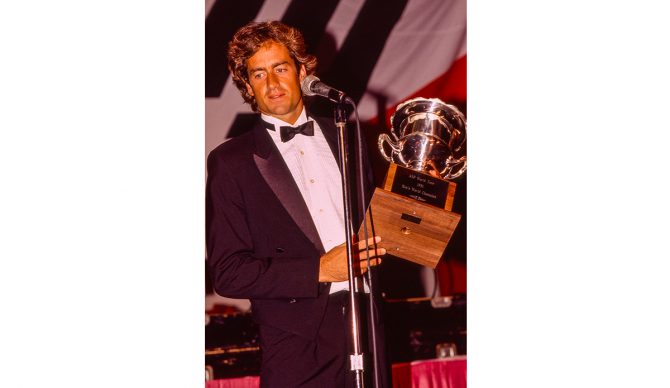

Just one highlight from Tom Curren’s emphatic performance in the 1990 O’Neill/Pepsi Coldwater Classic. Photo: Peter Brouillet

Editor’s Note: In this exclusive, three-part series, The Inertia’s Sam George looks past the standard profiles and promotion to capture the essence of what has made the great Tom Curren truly a legend in his own time.

One of the best places on Earth to watch surfing is from the low sandstone bluffs along West Cliff Drive in the Northern California city of Santa Cruz, looking down on the waves of Steamer Lane. This, in turn, makes Steamer Lane one of the best places on earth to hold a surf contest, the vantage of both the judges and spectators being as close, and as close to ideal, as anywhere else, other than perhaps the Huntington Beach Pier. Which Steamer Lane definitely is not: compare the two in front of any Santa Cruz local at your own peril.

But while throughout the 1980s numerous amateur and regional professional events had called the Lane home, without a doubt the apex of surfing competition at Steamer Lane came in 1990, with the third running of the O’Neill/Pepsi Coldwater Classic. First held in 1988, the CWC was the first World Championship Tour event to take place north of the Ventura County line, dropping big-time pro surfing into a totally new environment. With an appropriate Westside Santa Cruz vibe, the contest’s tagline snarled “Go Big, Or Go Home.” With the previous two events won by WCT standouts Richie Collins and Martin Potter, respectively, 1990’s Coldwater Classic was one of the ASP tour’s most highly anticipated extravaganzas.

So, it’s understandable just how nervous a young Pleasure Point local might’ve been on that first morning of competition, reenacting the timeless dawn surf contest ritual of checking the heat sheets, posted at the base of the judging scaffolding. And you bet he was nervous — he’d worked hard to get a spot in the first round of the trials. A decent NSSA ranking, a couple reasonable PSAA results; the pride of Pleasure Point’s First Peak. Now, looking around at the big-top circus that he was finally a part of, he felt confidence surging as he ran his finger down the already saltwater-dimpled heat sheet, looking for his name. Found it. Then, right above his name, what the…? You kidding? What was this guy doing in the trials? He looked up at an O’Neill dude he knew. “Is this a joke?”

“No joke,” said the O’Neill dude. “He’s coming out of retirement. Tough luck, bro.”

Tough luck, indeed. Because rather than on the Day-Glo, billboard-sized, top-16 seeding bracket displayed atop the scaffolding, tacked-up down on the salt-stained sheet of paper was a name he never imagined to see in his first-round trials heat. And just like that, our young Pleasure Point local felt as if he were about to become seasick.

“What the hell is Tom Curren doing in my heat?”

Yeah, that Tom Curren. The two-time World Champion Tom Curren. First American to win a professional world title Tom Curren. The guy who, still in his teens, won the very first contest he entered as a pro, out-surfing all comers at the Stubbies Pro, held in clean conditions at Lower Trestles. Who then hopped on the ASP World Championship Tour, the path ahead smoothed by a combined $40,000 contract with Op and Rip Curl, a record haul for a rookie. Who won a world championship tour event, first time out; won his first world title in 1985 at Bells Beach, topping Mark Occhilupo in one of the greatest semifinals performances in surf contest history. Then took home his second world title in 1986, the year he won five of that season’s first 10 events. And won consecutive Op Pro titles (’83-’84) at the Huntington Beach Pier, and just for fun, won it again in 1988. The surfer who, by 1990, had dominated the prestigious SURFER magazine Reader’s Poll, topping the men’s charts for six straight years. The surfer who, regularly competing against at least a half-dozen of the world’s best surfers (as opposed to today’s men’s world tour, populated by a couple greats and a bunch of guys trying real hard) consistently rose above them all in terms of style and influence; the period’s biggest surf star.

Against all odds, on top…again. Photo: Tom Servais

So, sure, tough luck, bro. But truth is, however, is that none of the Coldwater Classic competitors should have been surprised to find Tom’s name on that heat sheet. Cold water or not, this was classic Curren; just another chapter in the myth that had built up around the modern sport’s most unknowable icon. Because despite an incredible, extensively-documented contest record, all anyone really knew about Tom Curren was that nobody really knew what to expect next from Tom Curren. Preternatural surfing skills, an almost mystical connection with the waves, a baffling combination of extreme focus or often hilarious absentmindedness; he was obviously operating on a completely different wave-length than the rest of us. As just a few of the following stories that reveal the man behind the myth will attest.

Consider, for example, Tom’s very first professional debut at the 1982 Marui Pro, held at Japan’s Hebara Beach. Having surfed his way out of the trials and into the semifinals in pumping, left-hand beachbreak conditions, he came up against 1977 world champion Shaun Tomson.

Every wave ridden so far in the competition had been a left, and Shaun, no doubt wondering what his young competitor was doing suddenly drifting away, far from the lineup, took wave after uncontested wave on his backhand, confident, upon returning to the beach at heat’s end, that he had crushed the poor rookie. Until they told him: Tom had paddled down the beach and caught a big right where throughout the entire event there had been no rights, not one. Except this one: a perfect 10-point ride. Not crushing the veteran, exactly, because Tom wasn’t actually competing against Tomson. He was just following his senses. After this geographically appropriate Zen performance, beating Tom Carroll in the final was a foregone conclusion. In classic Musashi form (“Win your battles by acting from the timing of the void, tempered with the timing of intelligence which perceives the enemies’ patterns. Thus, respond with superior timing and catch the enemy unaware.”), Tom later went on to win two more Marui crowns, earning him “samurai without a sword” status.

In the summer of 1981, while visiting friends in California, a 16-year-old French surfer named Marie Delanne stops by the Channel Islands surf shop on Helena Street, in Santa Barbara. There, she happens to meet 17-year-old Tom Curren. They go surfing together (although exactly who drove them to the beach has been lost to history — Tom had no license). They fall in love. Marie returns home; a long-distance romance ensues. Tom, surprising everyone except those who know him well, becomes semi-fluent in French in a couple of weeks. The love-sick pair manage short visits in Hawaii and France. Two years crawl by and Tom, a surf star now, calls Marie to tell her he’s off to Australia for a long leg of the tour and that they might not see each other for quite a while. He changes his mind at the last minute, and instead proposes marriage. It’s a teenage wedding, and Marie joins Tom on tour Down Under. Celebrating the newlyweds on Gold Coast radio 4GG, the DJ plays Billy Idol’s “White Wedding,” with a typically laconic Tom later commenting, “Odd choice for a first dance.” Not only romantic, but monogamous at age 19 — it’s clear by now that Tom is the odd one, especially by Australian standards.

Traffic on Oahu’s Kalaniana’ole Highway was barely crawling, backed up all the way to the Halona Blowhole Lookout as surf fans and civilian tourists streamed east out of Honolulu to Sandy Beach, site of the 1986 Gotcha Pro. The beach park was a zoo, the huge crowd bulging out of the parking lot and onto the sand — the final round of a raucous bikini contest had been held to give the top four surfers a break before the semis. Brad Gerlach and Hans Hedemann stood ready, as did Derek Ho. His competitor Tom Curren was nowhere to be found. Announcers brayed over the din, “Tom Curren, please check in with beach marshal Rabbit Kekai. Tom Curren, please check in.”

Nothing. No Curren. Minutes tick down. No byes back then — Ho would paddle out alone, have the Pipe Littles lineup to himself. The last bikini contestant tottered her way back to the safety of the changing tent, the first semi was about to start. Suddenly came a rumbling roar from down by the bathhouse. Heads swiveled as one to see a gnarly looking biker on a chopped-out Harley weaving through the traffic cones, Tom Curren precariously perched behind him, one arm around the biker’s waist, the other holding his CI thruster. Seems that Tom (who had never owned a watch in his life) found himself again running late and mired in the gridlock. Abandoning the first of what would be many rental cars, he struck out on foot, only to be fortuitously scooped up by the sympathetic biker, who obviously knew a little something about surfing’s who’s who. With barely time enough to catch his breath, Tom won his semi, then went on to beat Gerlach in the final. Then he hitched a ride back to his rental car, the tall first-place trophy strapped to the roof a friend’s car.

It’s a warm afternoon in 1987. On the living room floor of his Carpenteria, California condominium, Tom Curren sits cross-legged in front of a brand-new entertainment console, industriously working his way through a selection of cassette tapes, picking out songs to play for friend and SURFER magazine contributing editor Matt George. Talk comes easy between various cuts from Tom’s characteristically eclectic musical library, ranging from Stan Ridgeway and Gary Newman, to Aretha Franklin and Al Green. George, also sitting on the floor, idly picks out a month-old issue of “Rolling Stone” from a basket of magazines; all of the surf mags in the basket are Japanese. Finished perusing, he’s about to toss the magazine back into the basket when he notices something stuck to the back cover, as if it had got wet. Curious, he peels it off, turns it over, and sees that it’s a bank check: Tom’s runner-up check, to be exact, from that season’s Marui Pro in Chiba, a number of weeks old and filled out somewhere close to $9,000 U.S. Shaking his head, George looks over at Tom, currently deep in appreciation of Ridgeway’s “Walking Home Alone.”

“Hey, Tom,” says George, holding up the check. “You been looking for this?”

“Oh, that’s where it was,” says Tom, smiling sheepishly. “Umm…hey, uh, don’t tell Marie, huh?”

In the years to come, numerous, mostly apocryphal stories with the theme of “Misplaced Curren Checks” would circulate. This one, though, actually happened.

During a short break from the tour in the mid-1980s, Tom, with absolutely no prelude and in a very non-surfer-like fashion, eschews his peers more characteristic distain for any other form of exercise but surfing, and embarks on a serious fitness regimen. Focusing on high-intensity beach sprints to improve aerobic capacity, and body-weight plyometrics to torch explosive, fast-twitch fibers, Tom returns to competition having packed on 20 pounds of muscle, his quads bulging in their Op lycra surf tights like an Olympic speed skater’s. The much-lauded “Curren double-pump” bottom turn? Yes, Al Merrick’s finely-tuned shapes and the Rincon test track played a huge role in the development of a technique that would radically change the direction of high-performance surfing. But when it came to holding his board on rail off the bottom, backing off just slightly, then re-engaging the rail all the way up into the lip, all that new muscle certainly helped. Just like that, virtually every one of the championship tour’s top contenders (with the exception of the already super-fit Tom Carroll) immediately begin reassessing their bird-legs.

So, it bears repeating: knowing this was Tom Curren they were talking about, should anyone have been surprised that after unexpectedly dropping the mic following his ’88 World Title to spend a year starting a family and surfing bucolic French beachbreaks, Tom Curren decided to return to professional competition, entering the 1990 O’Neill/Pepsi Coldwater Classic as an unseeded trialist?

The improbable beginning of the greatest comeback in competitive surf history. Photo: Tom Servais.

“I just felt like traveling and competing again,” said Tom, in response to a surf journo’s question as to why he chose to re-enter the tour’s hectic hurly-burly. “That’s how I make my living.”

Of course, what happened next truly became the stuff of legend. By the time Tom Curren stood on the Coldwater Classic’s scaffold, covered in confetti and holding his first-place trophy aloft, he had won his way through a total of nine heats. This included his first main-round match-up with 87’ CWC winner Richie Collins, who appeared so flustered by Curren’s aura of invincibility by this point that he blew two good waves and never recovered. The final against a hard-charging Gary Elkerton, who himself looked unbeatable in his semi, wasn’t even close — all five of Tom’s scored rides were in the excellent range. And so, on that chilly, late afternoon in Santa Cruz, a huge crowd packed the bluff at Steamer Lane, jammed up against the scaffolding, all eager to be a part of the elusive surf star’s improbable return to the winner’s stand.

It was the beginning of the most incredible campaign in competitive surfing history. Records show that by the time of Tom’s CWC victory, eleven pro surfers had won an event from the trials (one of those being Curren himself, at the ’82 Marui Pro). At age 26, competing as a trialist throughout the entire 1990 ASP World Tour (with the exception of a few wildcard berths), Tom Curren won a total of seven out of that year’s 18 events on the way to a third world title.

And then, poof…he was gone.

In Part III of “The Legend Of Tom Curren,” the decidedly enigmatic surfer’s remarkable, and even more vastly influential post-competitive career and contributions to the sport, are put into proper perspective. Read Part I of the Legend of Tom Curren, here.