Seaweed has been having a real moment for the last 20 years, and it could have profound consequences. Photo: Unsplash

For the last 20 or so years, seaweed around the world has been having a heyday. The rise in Earth’s overall temperatures coupled with fertilizer runoff entering the seas at record rates is making for ideal growing conditions. Which is good for seaweed, but bad for a lot of other things.

Seaweed’s rapid growth has researchers worried. In a recent study published in Nature Communications, they warn of a potential “regime shift” in our oceans.

According to the study, while it was clear both microscopic algae and macroscopic algae have increased in certain coastal and open waters, comprehensive global studies were lacking.

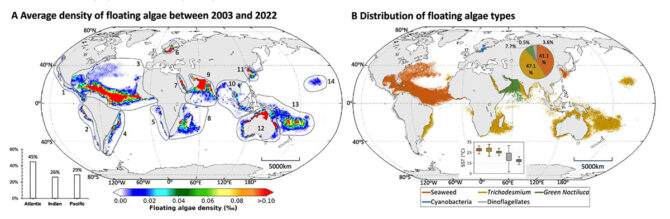

“Here, we address this challenge by analyzing 1.2 million satellite images with computer artificial intelligence to quantify macroalgal mats and microalgal scums in global oceans between 2003 and 2022,” the paper reads.

“With a total cumulative realized niche area of 43.8 million km2, macroalgae blooms in the tropical Atlantic and western Pacific both expanded at unprecedented rates since the 2010s (13.4 percent per year since 2003). Although slower, the annual expansion rate of microalgae scums is also statistically significant (1.0 percent per year since 2003). Such trends are likely a result of ocean warming and eutrophication, with a possible regime shift favoring macroalgae and specialized species of microalgae. These findings have broad implications on ocean ecology, carbon sequestration, environments, and economy.”

The numbers are pretty staggering. In the last 20 years, seaweed blooms have increased by 13.4 percent a year in the tropical Atlantic and western Pacific. The biggest year for seaweed growth was 2008, but that was one spike in an up-ticking chart.

There are a multitude of issues that arise from too much seaweed growing. One of the worst is that huge, sprawling mats of seaweed can significantly darken the waters beneath them, which changes the ecology and geochemistry that the creatures below have evolved to live in. Algae blooms can be toxic, as well, and the tiny animals that feed on algae ingest the toxic growth and move it on up the food chain, leading to all sorts of awful things, like domoic acid poisoning.

A Mean FA areal density determined from MODIS observations between 2003 and 2022, where their surface areas are partitioned to the three major oceans (inset). Based on their locations and dominant types, they are grouped in the annotated 14 zones, with dominant type(s) listed in Table 1.

“Before 2008, there were no major blooms of macroalgae [seaweed] reported except for sargassum in the Sargasso Sea,” said Chuanmin Hu, a professor of oceanography at the USF College of Marine Science and the paper’s senior author. “On a global scale, we appear to be witnessing a regime shift from a macroalgae-poor ocean to an macroalgae-rich ocean.”

There is one fantastic example of the phenomenon: the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. Visible from space, it stretches from the Gulf of Mexico to the mouth of the Congo. There’s also a ring all the way around the Chatham Islands off New Zealand, and Florida’s red tide is also a result of this.

The team of researchers says this study is the first one to show a true global picture of the algae in the world’s oceans.

“What is noteworthy is that most increases in both floating macroalgae and microalgae scums occurred in the recent decade, in line with the accelerated global ocean warming since 2010,” the authors wrote.

If indeed there has been a regime shift in the seas, macroalgae will take top billing from microalgae. That could have knock on effects to the environment as a whole.

“If this is the case,” researchers wrote, “we believe that a regime shift in oceanographic conditions has already occurred to favor macroalgae, which will have profound impacts on radiative forcing in the atmosphere and light availability in the ocean, as well as on carbon sequestration, ocean biogeochemistry and upper ocean stability.”