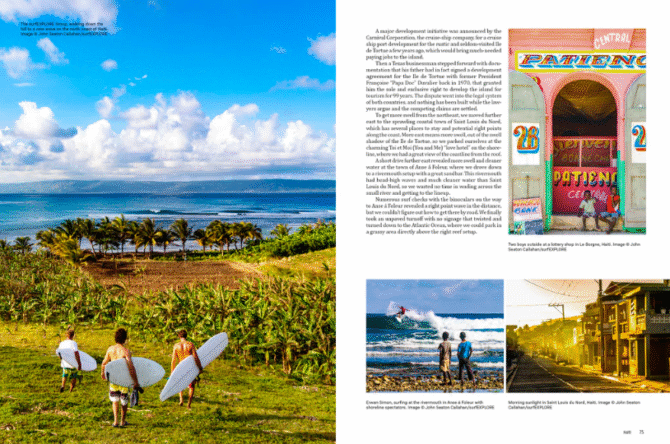

Callahan, deep in discovery. Photo: surfExplore

It was in a remote quadrant of the Indian Ocean, on the deck of a chartered motor-yacht, hove-to off the shore of Little Andaman Island, that I got a clear picture of how committed photographer John Seaton Callahan was to his singular brand of global surf exploration. Following a protracted voyage from Thailand, during which engine trouble twice forced a return to port, the assembled crew of pro surfers recruited by Callahan to be the first-ever to visit this far-flung, ordinarily off-limits archipelago (to non-Indian nationals) were restive, to say the least. So that when at the very first spot marked on Callahan’s British Admiralty charts they found a perfect, peeling six-foot left reef break, it seemed that the corrosive mix of hardships and boredom were washed away by the magic of a pristine surf discovery.

Or so it seemed, until after only a few hours of surfing — the first in weeks — Callahan called the surfers back to the boat, commanding the skipper to pull up anchor and continue the search further along the island coast. A veritable mutiny ensued, with one particularly incensed pro threatening bodily harm (no names, at least not here.) Callahan stood his ground, however, insisting that the whole point of this expedition — which he was solely responsible for arranging — was to explore the globe’s remote coastlines. And with swell in the water, and conditions ideal, who knew what we might find around the next distant point. The crew wasn’t buying it, but none were too keen about swimming home, so they sulkily clustered up in the bow, muttering protests. Yes, muttering, until revealed around that distant point was an epic, tropical Jeffreys Bay: long, uniform lines of spinning tubes, never-before seen by another surfer.

That incident at sea was Callahan in a nutshell; no one in the history of the sport has taken the search for surf as seriously, and has chronicled those surfaris so comprehensively. As exhibited in the new book surfEXPLORE — Discovering New Surfing Locations Worldwide, a massive, full-color volume profiling expeditions to 28 of the countries on whose shores Callahan has focused his lens and fertile imagination. Seemed like a good time, all these years later, to catch up with John for perspective on his endless quest for untracked waves. You could say I owe him — that session in the Andaman point break was one of the greatest experiences of my life.

After years making a name for yourself shooting surfing in Hawaii, what first triggered your shift from what might be called “conventional’ surf photography,” to scouring the planet to document previously unridden waves?

I grew up in Hawaii and when you look at a map, it is very clear – the Hawaiian Islands are but tiny dots in the vast, open expanse of the North Pacific Ocean. I think it is only natural for island people, once they have thoroughly explored their small part of the world, to wonder “what else might be out there?” and if they have the time and the means, to go out and look around. That’s what I’ve been doing.

There has also been a shift from the “someone” to the “something” in the surfing photography world. Now that we are past the magazine era, there is less emphasis on personalities in surfing and as surfing has spread around the world, people are more interested in the “where” than the “who.”

In magazine days in the 1970s and ’80s, when the surfing world was much smaller, personalities sold magazines and made advertisers happy so photographers were encouraged to focus on people. Now, personalities fuel growth on individual Instagram accounts and surfing editorial images are more focused on where – giant waves at Nazaré, Maverick’s and Teahupo’o and of course; the all-time favorite, the mystery lineup with no one surfing that can result in hundreds of comments for a single image in a large Facebook group like Legendary Surfers with 300,000 members.

There’s always plenty to explore in Indonesia. Photo: John Seaton Callahan

Describe an experience on one of your earliest expeditions that really set the hook, inspiring you to become more serious about your surf exploration efforts.

I think some of those Isla Natividad projects with SURFING magazine were instrumental in stoking my interest in finding new waves in other places in the world. Not only did Natividad have very good waves, but the whole story that Larry “Flame” Moore told about figuring out the setup with Sean Collins – the normal onshore wind for most of Baja California Sur would actually blow offshore at Natividad, as the island was positioned far enough west so south swell could make it to the east side of the island. It was putting together the different variables of swell, wind, tide and location that was appealing, so I started thinking about how to apply this rational thought process to other locations that might have good waves.

Before sophisticated surf forecasting and Google Earth, what tools did you rely on to remotely search the world’s coastlines and oceans for remote, undiscovered surf spots.

It wasn’t easy – paper maps of some type were the only source of information. Most maps published at this time were intended for driving, showing roads and intersections, so not particularly useful for anything to do with the shoreline or the ocean.

As looking for new waves involves ocean bathymetry as much as the land contours, the best source of information was a nautical chart, either the U.S. Defense Mapping Agency (DMA) or the UK British Admiralty series. When I was at UCLA, there were any number of specialty libraries on campus and one of them was the UCLA Map Library, which was small and rather obscure but was only maps! It was the first place I was exposed to a nautical chart and soon realized many of the DMA and British Admiralty charts were the same information, due to information sharing agreements between the U.S. and the U.K.

Describe your very organized magazine feature production protocol: which surfers you recruited for your expeditions, and why.

I was always looking for people who could bring more to the table than just their surfing ability. At the sponsored-surfer level, everyone can ride waves, I was always looking for people who had an interest in exploration, new places, new cultures, people who had some travel knowledge and experience so we could avoid the dreaded stereotype of the pro surfer who goes on an international surf trip for two weeks to Indonesia, Angola or Peru and never takes his headphones off except to go in the water and surf!

Certainly you couldn’t have always scored. Describe your most memorable “dry hole.”

Ha, ha, that’s true. I like to tell people “you can always score waves, it just depends how long you are willing to wait.” That is true up to a point, as no matter how much time, money, effort and research you put into a project, no one can control the ocean.

We have had several projects in The Philippines where we were in the right place at the right time, but there was no typhoon activity in the western Pacific, nothing. It was hot and sunny with 15 knots offshore southwest wind all day, every day but no waves – dead flat, not even a ripple. When you are spending a thousand dollars a day of other people’s money on a chartered live-aboard boat and there is no surf at all, people start getting anxious and soon, very soon, negative opinions regarding your leadership, knowledge and experience at doing this sort of thing are being expressed, to put it mildly.

For contrast, describe your most memorable discovery. Was it because of the waves you found, or some particular experience along the way?

We have had several situations where, looking at perfect, empty waves in a lineup that has never been surfed by anyone I couldn’t help thinking “This is what it’s all about – all the time, money, effort and planning, this is it right here.”

One of those times was the first day we pulled up at what we later called Kumari Point in the Andaman Islands and saw the long, offshore rights at the point, breaking through several hundred meters of flawless sections all the way to the beach with the Onge aboriginal village at the base of the point. This location had looked good on the charts with a northwest wind and a southwest swell and that turned out to be true, very true, and it is certain we were the first group of people ever to surf at this location. No one has ever come forward to claim otherwise!

When it comes to more traditionally organized “surf travel stories,” how would you characterize the difference between the standard “look what we found” feature, and the approach you’ve taken throughout the decades?

I would say it’s all about context. The kind of projects I have tried to do with The surfEXPLORE Group have always been about more than just the waves. We always look into the local culture, customs and particularly the people, how they react to having visitors in the area and if they want visitors or not. In the magazine days, editors like yourself were concerned with keeping editorial features on track and readers entertained and that meant waves and more waves, cutting the National Geographic stuff to a minimum and focusing on what surf magazine readers want, which is more waves.

surfExplore dives into Callahan’s many adventures, which entailed much more than just surfing.

In the face of years of the surf media’s hypocritical exploitation policy of “show but not tell,” you’ve always at least identified the countries you’ve visited. Explain why.

This is actually part of a much bigger question about the validity of “secret spots” – is concealing locations a valid strategy? Or is it just rich, selfish, white people trying to keep poor brown people poor for decades, so they can continue to return to their cheap paradise surf holiday locations season after season, being waited on by brown people and surfing high-quality, warm-water waves with as few rich, white Western surfers like themselves as possible?

In contrast, let’s look at one of the most famous waves in the world, Lagundri Bay on the south coast of the island of Nias in North Sumatra, a flawless reef break considered by many to be the best right-hand barrel in the world.

I have to think there are more than a few residents of Sorake Village, the village in front of the wave, who must wake up in the morning and think they are the luckiest village in Indonesia if not the world, for the incredible gift in their backyard. The waves were something that they did not grow or make, that had nothing to do with government or religion and that until in 1975 the three “orang putih“ [“white men”] turned up with surfboards, paddled out and started riding the waves in front of the village. Waves that up to that point had no purpose, but were, in fact, a hazard to the locals in their hand-carved wooden fishing canoes.

Once the word began to circulate, more surfers arrived in the village. Losmen were built to accommodate these visitors and money began to flow into Sorake. Growth was uneven until 2005, when a major earthquake in the region raised the sea floor approximately two meters, turning what had been a good wave into a roaring eight to ten-second barrel, improving wave quality while other famous waves in the area, like Bawa and Asu in the Hinako Islands, were not as good after the earthquake and eventually lost favor and visitors.

In the past 20 years, foreigners provided capital after the earthquake and more guest houses have been built, run by local families on their land in a cooperative arrangement, ensuring everyone in the village who wants a job can have one. These guesthouses provide an endless supply of income to local families for nine months of the year, as thousands of international visitors travel tens of thousands of kilometers to arrive at an obscure village on Nias Island to surf one of the best waves in the world.

This massive increase in living standards has made Sorake the richest village on Nias and is entirely attributed to international visitors and their money, an increase in wealth which never would have happened at all if Lagundri Bay had been kept as a “secret spot” for the benefit of a few rich, white Western surfers and their friends.

I’m sure you remember that time in the Andamans, when, after everything it took for you to get the Crescent and crew to that remote spot on the map, and happened to find a perfect, six-foot left reef break, you experienced a near-mutiny when you announced we were pulling up anchor and proceeding to explore the rest of the coastline while the conditions were so ideal. Had anything like that happened to you before, or has it since?

Yes, that was a difficult situation, to move the boat from a location with very good waves after all the difficulty and drama just to get there, yet with the incredible waves we found at Kumari Point, it turned out to be the right decision. But we’ve had similar situations on other projects, when moving was not something other people wanted to do. One of them was on a live-aboard boat off the coast of Morotai in North Maluku province of Pacific Indonesia. After a long transit from Manado in Sulawesi, we were at a good left reef wave, a wave that has since become one of the more popular waves in this area, and there was swell and good conditions. And just like that time in the Andamans, most of the surfers on the boat just wanted to stay there and surf. And again, I said we need to move and look around exactly because we have good swell and conditions. If we wait until it goes flat, we could go right past setups that we can’t see because there is no swell. It took an hour or so of spirited discussion to convince everyone to pull the anchor, but we were rewarded with a nice right-hand point later the next day that we probably would have gone right past it if we had been looking when there was no swell.

surfEXPLORE — Discovering New Surfing Locations Worldwide is available from Schifferbooks.