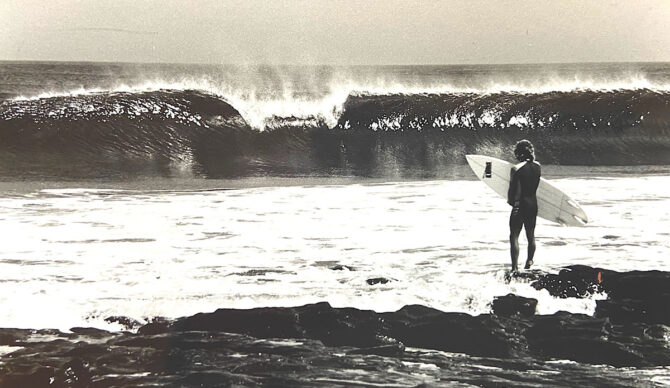

“Make sure you have a receipt for that board.” Photo: FLAME

Editor’s Note: “Scrapbook” is a limited series from The Inertia’s Sam George, in which the longtime surf scribe draws from a vast trove of personal stories and photos to present a collection of entertaining tales that, while spanning decades of his surfing life, are easily relatable to any of us who’ve joined him in that pursuit.

The year was 1986 and I was sitting at my desk in the office of SURFING magazine, where I held the job title of Senior Editor. Which, on this particular day, meant I was leaning on my elbow, chin in hand, staring out the building’s broad, glass windows at the view of the distant Pacific, contemplating the theme of my next monthly “Caught Inside” column. Maybe recounting my latest battle with various airlines over excess baggage fees levied on surfboards, or an opinion piece rationalizing why I hate getting up early for the ritual “dawn patrol” surf session. Serious stuff.

My flow of thoughts was interrupted, however, when I looked up and found Dina, the magazine’s accounting manager, standing next to my desk, a grave expression clouding her normally affable features. Not only had she never personally addressed me other than to offer a friendly hello in the lunchroom, I’d never once seen her in the upstairs offices. Like I said, serious stuff.

“Hey, Dina. What’s up?” I said, keeping it casual. “Can I help you with something?”

“I’m not even supposed to be talking to you, Sam,” she said. “And I’m certainly not supposed to be telling you this.”

“Excuse me?” I asked. “Not telling me what?”

“I’ve received a ‘Final Notice of Intent to Levy’ today,” she said. “Starting tomorrow the IRS is going to freeze your bank account and begin garnishing your wages for unpaid taxes.”

“What?” I asked again, uncomprehending. “I don’t remember getting any notices before this.”

How would I have, considering my inexplicable, and now wholly lamentable habit of tossing into the wastebasket just about any envelope with a window on the front. This could easily explain why the IRS had eventually gone straight for the source of my paycheck to exact their due.

“They’ve contacted me directly,” said Dina, “And have directed me to forward them fifty percent of your disposable income until further notice.”

“But I don’t have any disposable income,” I said. “I spend every penny I make just getting by.”

And trying mightily to say these words without completely emasculating myself — Dina, standing far to the right from the staid accountant’s stereotype, and who could’ve just as easily been one of our advertiser’s swimsuit models, wasn’t the sort of woman you wanted to whine in front of.

“Exactly,” said Dina, but kindly, without a hint of the recrimination one might expect from an accounting manager. “The issue apparently has something to do with your expense deductions. That’s why they don’t want me to speak to you, so as not to give you time to, I don’t know…”

“Time to do what?” I sputtered. “If they take half my paycheck and freeze my bank account, what am I supposed to do?” How am I supposed to live?”

Now I was whining. Dina cast a glance over her shoulder before speaking again.

“What you should do, Sam,” she said, in conspiratorial sotto voce. “Is get to your bank right now and withdraw every penny. Then tomorrow call the IRS and set up an in-person interview. Just don’t tell them we spoke.”

Had I dared I would have hugged her. Instead, I got up from my desk, thanked her in the same guarded undertone, and hustled off to immediately take her sage advice.

Connecting to the regional IRS office by phone the following day (after I’d waited on hold for three hours) I was told to be prepared for “an examination to be conducted through an in-person interview and review of taxpayer records.”

“In-person”—they made it sound so friendly. Yet there was nothing accommodating about the eventual scenario, which found me sitting with a battered box of “receipts” on my lap in a very typical, predictably prosaic government office: framed portraits of President Ronald Reagan and Vice President George W. Bush dutifully beaming down at the green linoleum floors, grim overhead fluorescent lighting, gray fabric partition dividers forming opposing cubicles, black metal wastebaskets under gun-metal desks topped with black plastic multi-line phones with twin rows of blinking red buttons. None of the spaces occupied, save one.

The man sitting behind the desk, unlike the good Dina, perfectly fit the typical accountant’s stereotype: narrow shoulders, short dark hair, black-rimmed glasses, neatly trimmed mustache, blue short-sleeved business shirt worn with dark blue tie, outline of the undershirt discernible. Far from an imposing figure, but given the inherent power at his fingertips, still intimidating. We didn’t shake hands.

“Mr. George,” said the anonymous taxman.

“That’s me,” I said, taking a seat and placing the cardboard box at my feet.

“We’re here today to conduct an in-person interview and review of taxpayer records,” he said. “And first off I need to inform you that you have the right to be represented during said interview and review by an attorney.”

“That won’t be necessary.” I told him. “Because I haven’t done anything wrong.”

He almost sighed as he perused a sheaf of documents on his desk.

“It’s indicated here that your 1985 return was flagged for insufficient documentation of business expenses.” he said.

“Sure,” I said. “But that doesn’t mean I did anything wrong. It just means that you don’t believe me. Basically, you’re calling me a liar.”

“Not providing adequate documentation on form 1099 is a serious issue,” said the taxman, sounding a bit off balance.

“Yes, but let’s get things clear,” I said. “I’m here today not because I’ve done anything wrong, but because the IRS is saying that I lied.”

“There’s no need to make this personal, Mr. George.” said the taxman.

“There’s every need to make this personal,” I said. “Because the way I see it, the IRS, and the United States Government, is saying to me, Sam George, ‘Liar, liar, pants on fire.’”

The taxman paused, as if in consideration.

“Well, essentially, yes, you could put it that way.” he said.

“Good,” I said with a smile. “So, with that out of the way, let’s get on with the interview part. What do you need from me?”

“As I said, adequate receipts for business expenses listed,” he said. “For example, you’ve indicated here a total of three surfboards at roughly three hundred dollars each.”

“Hey, and that’s getting them at cost,” I said. “It would be even more if I had to pay retail.”

“That’s beside the point,” he said. “Taxpayers aren’t allowed to deduct sporting equipment.”

“A surfboard isn’t sporting equipment,” I said. “Not when you work at a surfing magazine. It’s a business expense. To properly do my job, I have to surf pretty much every day. And on the best surfboards possible.”

“That’s all well and good,” he said. “But I’m going to need receipts. Proof that these surfboards did exist.”

“I’ve got that,” I said, and reached down into my cardboard box, coming up with two bound volumes containing all twelve of the monthly 1985 issues of SURFING magazine. I stood and leaned over his desk, flipping through the pages. “See, look. This is a story I did about surfing on an island in Baja California. And this photo shows me standing on the rocks, getting ready to paddle out, holding my 6’2″ Channel Islands, shaped by Al Merrick, with the new logo that only came out last year. Clear proof.”

Dubious hardly describes the look the taxman gave me. I continued flipping pages, landing on another feature.

“Uh, do you have documentation for that?” Photo: Shutterstock

“Here’s an article I did in March, comparing polystyrene/epoxy surfboard construction to traditional polyurethane/polyester,” I explained. “And that’s my John Bradbury polystyrene board in the picture, used as an example, unwaxed. Brand new, as you can see.”

I pressed on, not giving him any time to comment.

“And the third board,” I said. “Well, see this story about surfing big waves at a spot in Baja called Isla Todos Santos? See the board I’m loading into the panga?”

I reached into the box and pulled out the front 16 inches of the board’s nose, the foam and fiberglass torn ragged, presenting it like a crucial piece of evidence.

“Mr. George,” the taxman said.

“Wait,” I said, and pulled from the box a broken surf leash, its urethane cord snapped cleanly three feet back from the ankle strap.

“You’ll see I even listed the cost of the broken leash, too.”

Did I notice a subtle shift from dubious to bemused? He looked back down at my toxic tax return.

“Well, here, listed in travel expenses,” he said. “One-hundred dollars for a Balinese board carrier? Is that a person or a thing?”

“A person,” I said. “And yeah, that’s a whole lot more than they usually charge, but that was for the whole trip, and she has a family to support. I don’t know if you’ve ever been to Uluwatu, but none of the villagers there give out receipts. They operate more on the honor system.”

Even as I said these words, I knew they sounded ridiculous, possibly bordering on sarcastic, which is hardly the tone to take with the IRS. Didn’t matter, though — I was a dead man walking the moment I entered that creepy office.

“This is all very colorful, Mr. George,” the taxman said. “But hardly sufficient. I’m afraid we have no choice but to proceed with the wage garnishment and levy on your bank account until such time you make restitution of the estimated taxes, plus payment of a punitive fine to the amount of 900 dollars.”

“Seriously?” I asked. “Nine-hundred dollars? And how do you suggest I pay all that back and still eat, or keep a roof over my head, or gas in my truck?”

“Try holding on to your surfboard the next time,” he said, a very subtle smile causing his mustache to twitch. “And start keeping receipts.”

It was almost one year to the day that I found myself back in that IRS office. This time I was faced by a much more formidable character, a broad-shouldered woman of middle age, a gaily flowered blouse belying her true nature; narrowed eyes and stern, close-set lips told the real story. She wasted no time, but got directly to the point.

“Mr. George,” she said, with a tone I’d heard quite often from various elementary and high school teachers — and even a few Catholic nuns — throughout my youth. “Just who do you think you are?”

How are you supposed to answer a question like that?

“Here, on your 1986 form 1099,” she said, barely suppressing what was obviously considerable outrage. “The $900 fine levied against you last year listed as a business expense?”

“I did one of my monthly ‘Caught Inside’ columns about last year’s trip to the IRS,” I said. “Figured I’d write off the fine as research. Here, I brought the issue…”

I don’t have to tell you how that turned out. But I will say that I’ve written off my surfboards as business expenses every year since. And kept every receipt.