That thing has come a long way for you. Photo: Kevin Strickland

If you’ve been surfing for a while, or just curious about waves in general, you may have asked yourself a very simple question: where do waves come from? You probably have a basic idea, but let’s dig a little deeper.

Some of us only have small windows in which we can get out for a surf, so we may go out no matter the quality or size of the waves. Others may have the luxury to wait for the ideal time to paddle out. Either way, it is good to know the basics of where waves come from and how they form. Waves, after all, are the foundation of surfing.

Where Waves Come From

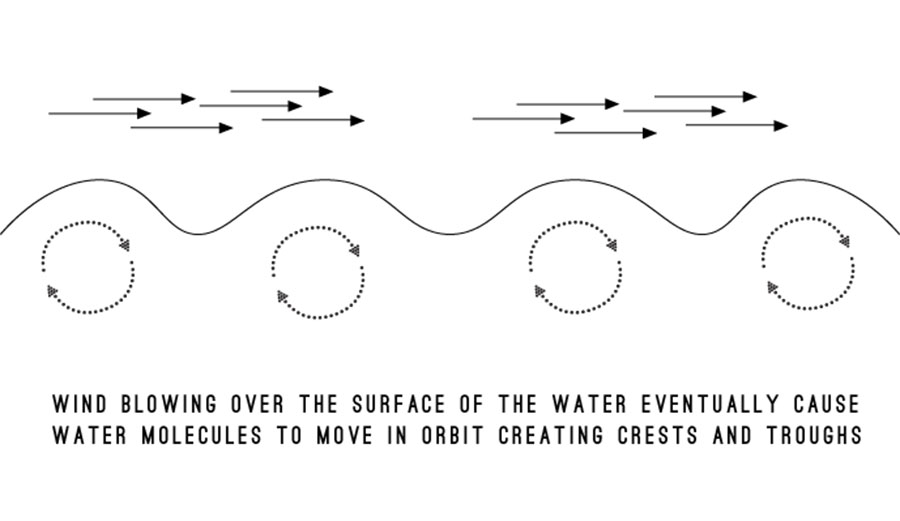

It all starts with wind. Basically, waves are generated by wind. Offshore storms far out to sea generate wind that blows across the surface of the water. As it continues to blow, ripples begin to form on the surface and the more the wind continues to blow, those ripples get easier and easier for the wind to catch, causing the ripples to grow in size.

In the beginning, there was wind.

On whether maps, the wind is shown in the form of a low pressure system. The more tightly compacted the isobars around the low pressure system, the stronger the wind. The initial waves created will be moving in the same direction that the wind is blowing. The longer and stronger that wind blows, the bigger the waves become. Because the wind can grab a hold of these waves easier than the flat surface of the water, as they increase in size, the waves will carry more energy across the surface of the water.

The size of the waves, however, is limited to the initial strength and speed of the wind. Winds of a certain speed can only generate waves of a certain size. Once these waves are at their peak in size, the are considered “fully formed.” The waves closer to the system may seem jumbled up and in a bit of a state of chaos, but as these “fully formed” waves move further and further away from the system, they begin to organize themselves into steady lines of swell.

Some of these waves will have different speeds and wave periods. The longer period swells move faster and carry more energy than the slower period swells. These will continue to move forward until they are either disrupted by a mass of some sort (i.e. and island chain, reef or beach) or just until the travel so far that they run out of they own energy.

The waves that are still moving forward but are no longer affected by the wind are considered ground swell. This ground swell is really what we, as surfers, are looking for. They are more organized and you can predict the sets approaching to some degree.

Basically, a low pressure storm very far off the coast sending waves your direction will produce ground swell that hits your shores. A low that is closer to your coast will produce what is called wind swell, which can be equally as fun to surf, just more unpredictable and disorganized than the ground swell that we all love.

How Waves Get Their Shape

Ok, now that you have a brief idea of where the waves are coming from, lets dive into how waves get their shape.

Let’s consider a nice ground swell. As these low pressure systems spin off the coast generating swell, the minute the swell is fully formed, or no longer affected by the wind, it slowly starts to lose its energy. Unless, of course, it hits an object of some sort first, like an island chain, reef, or beach.

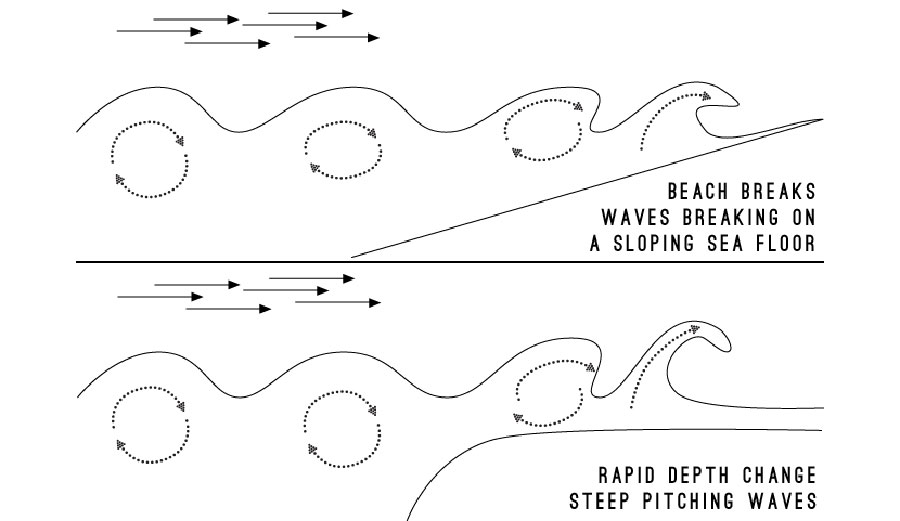

As that energy traveling from deep water comes into contact with the shallows of an island, reef or beach, the waves will feel the bottom and begin to steepen until it comes to a point (crest) where it will topple over.

The difference between waves coming up a sloping beach or hitting a steeper shelf.

If those waves are traveling across the bottom of a gradually rising beach break, the waves will break a little softer. If they come straight from deep water and hit a shelf like a reef or rocks, they’ll stand up and break much faster. They are usually much heavier than waves breaking up a sloping beach. Even the smaller waves can have more power than a bigger sloping beach break.

When you combine the various degrees of wave strength and speed with the varying types of shallows it can hit, you can have waves forming anywhere from ankle high to 60 or even 100 feet… really, the height of a breaking wave could theoretically be limitless. It all depends on the source.

Now, if the swell is hitting the reef or beach straight on, the shape of the waves for surfing is not going to be too great. This is what is called a closeout, or walled up. To have a surfable wave, you want it to have somewhat of a shoulder, which requires the waves to break at an angle to whatever mass it is hitting.

With beach breaks, you want to look for where the sand bars might be and if the angle is right for the swell hitting that sand bar, you are looking good. Reefs don’t move, so they are generally fairly predictable given a particularly angled swell, as are point breaks, only they usually generally offer a longer ridable wave as the swell hits the tip of the point first and the energy is allowed to run along side the bottom for quite a while.

There are so many other factors involved that we have yet to touch on, such as local winds and the tides. The same swell with a high tide onshore wind flow is going to be a lot different than if it was low tide and offshore. So much so that it can mean the difference between fat, sloppy waves or hollow, perfect barrels.

So, take this info with a grain of salt and use it more as a reference in the back of your mind.

Of course, if you are the unlucky bunch like most of us who only have certain times of the day you can get out, just go for it. But if you have the time and the knowledge, you can make sure you score the best part of every swell no matter what the day or conditions.

This was originally published on Boardcave.com.