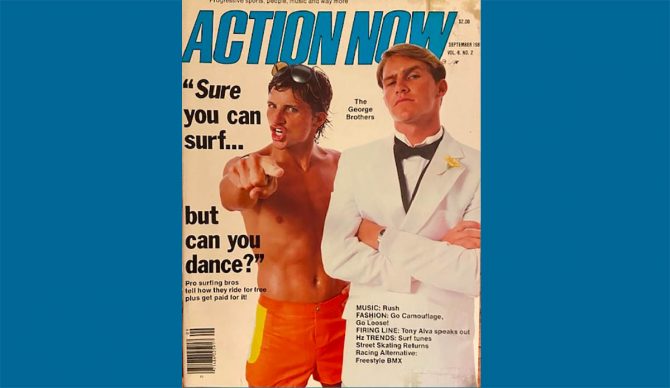

The brothers George, making this dance thing look easy. Cover photo: James Cassimus

Editor’s Note: “Scrapbook” is a limited series from The Inertia’s Sam George, in which the longtime surf scribe draws from a vast trove of personal stories and photos to present a collection of entertaining tales that, while spanning decades of his surfing life, are easily relatable to any of us who’ve joined him in that pursuit.

There is a developmental stage in young children referred to as “parallel play.” Out on the playground, for example, these particular kids, whose emotional IQ might not yet match their actual intelligence quotient, often find themselves alongside a group of children at play, playing the same game, yet not actually participating. In fact, most often the players engrossed in their game have no idea they are being shadowed. But for the lonely child on the sidelines, the dynamics are real and tangible. It’s just that they experience it all within themselves, rather than in relation to the other children.

This situation perfectly describes my brother Matt’s and my competitive surfing career. We were pro surfers because we said we were; because we wanted to believe that we were. That through our efforts we somehow snuck into the pro arena reinforced this belief system. We entered professional events, we participated on the world circuit; we waxed our boards, and warmed up before the contests and got nervous in heats just like all the rest of the pros. I even racked up a couple decent results. It’s just that nobody seemed to notice I was there, doing all that. Matt, with whom I traveled on several legs of the pro tour in the early 1980s, was simply a ghost.

But it’s not like we both didn’t give it our best. Take 1981’s South African/Brazil leg of the IPS World Tour, for example. As visiting Californians we were gifted entry in the trials rounds of the prestigious Gunston 500, held in Durban’s world-class, sand-bottomed jetty break known as Bay Of Plenty. As was my way, I advanced through a series of heats only to lose out right before the money round (I lost to Greg Day from Australia, but only just barely, damn it.) Idiotically, we had counted on winning some prize money to cover expenses like rent, food and entertainment. Back then a South African rand cost a buck forty U.S., so ancillary activities like taking local girls out to the movies (or in my case a mad, romantic rendezvous in far-off Cape Town) really ate into our budget.

A popular side event at the Gunston was the annual paddle race, which offered a R300 first-place prize. This thing was a big deal — many thousands of surf fans and beachgoers flocked to the Durban beachfront during the contest week, making this perhaps the biggest crowd to ever attend a paddle race. Having lost out in the trials, and having already hawked both of my custom-color Rip Curl wetsuits to a pair of lucky locals (Rip Curls were hard to come by in South Africa back then), I announced that I was going to win the paddle race and earn us the money to pay our back rent and have enough left over to at least feed ourselves when having moved on to Rio de Janeiro — by that point we had our round-trip tickets, and that was about it.

But South Africa is nothing if not a sporting nation, and those Durban guys took that paddle race seriously. Keep in mind, this was intended to be a surfboards-only event, with a seven-foot length limit — no long, sleek paddleboards allowed. This didn’t keep the crew at the venerable Safari Surfboards factory from designing an innovative, seven-foot surfboard/paddleboard hybrid, on which Safari team-riders very predictably won the race each year, with the rest of the field competing for the R150 second-place prize.

Undeterred, I ended up paddling an unwieldy, seven-foot polyurethane blank mold with a fin jammed through the glass in the tail (my 6’2” Channel Islands double-wing pin wasn’t going to cut it), head down and blowing snot bubbles all the way to a second-place finish behind Durban’s Marc Price on the custom Safari. Brother Matt, paddling his 6’0” Max McDonald, came in way behind the pack, dead last, in fact, but still raced up the beach and dove across the finish line, earning the loudest cheers of the day. Little did I know this wouldn’t be the last time he’d be hearing the roar of a crowd in Durban.

Couple nights later, after a frugal evening of bowling with fellow Californian Chris Barela, I returned home to our tiny rented apartment to find Matt dressing in front of a full-length mirror hanging on the back of the bedroom door. He was wearing black jeans, a pair of cheap, black Chelsea boots, and a black, long-sleeved button-up shirt, from which he had apparently cut the lapels. He looked like a blond flamenco dancer. It was 10:30 p.m.

“It’s ten-thirty,” I said. “Where are you going at this hour? And dressed like that?”

His nonchalance was completely believable.

“Remember Chata, that girl I met?” he said. “She and some friends are at the movies. I told her I’d meet up with her afterward.”

Reasonable. So, having twitched his curious sartorial arrangement into place, off Matt clomped on his Cuban heels, while I headed off to bed. I lay there on the double mattress we shared (heads reversed at opposite ends, naturally) for some time, staring up at the ceiling, gnawing at the prospect of still not being able to pay our rent, my paddle prize amounting to barely half the necessary amount. Sell my beloved double-wing pin, maybe buddy breathe boards with Matt in Rio? But what if we ended up in the same heat? After 20 minutes of pointless, ruminative thinking I resolved to push this dilemma out of my mind, and instead finally drifted off to sleep wondering why I didn’t think to ask Matt where he got those shoes.

I was awakened much later by something wafting across my face, a distinctive smell, the hair blown off my forehead as if by a fan. I stirred, blinked open my eyes and saw Matt, backlit by the light of the hallway, sitting on the edge of the bed, holding something fanned out in his hand. He tossed the something down on the bed, the numerous R20 notes making a hefty pile.

“What the…what is…,” I stammered. “Where did you get this?”

“Sam,” Matt said, in a tone of wonder. “I won the Club Med Disco Contest.”

Some backstory required. In 1981, South Africa was definitely a few steps behind the times culturally. Yes, I know, considering the country’s heinous apartheid policies none of us should’ve been there in the first place, and being young, politically heedless in our pursuit of pro surfing, and wanting so badly to surf Jeffreys Bay is certainly no excuse. But there we were in ’81, riding the crest of the global New Wave soundtrack, while South Africa was still getting it on in the disco. As evidenced by the big banners hanging all over the city, promoting the upcoming disco dance competition at Durban’s “Glamorous Club Med.”

This sideline event became a running joke among many of the international surfing competitors, most of whom had Walkman headphones glued to their ears whenever on land, nodding along knowingly to the doleful strains of British bands like The Cure, or rocking out to The Clash. Snarky jibes, like, “Tough luck in that last heat. Maybe you should try the Club Med Disco Contest!” Or, “Where you guys been? Practicing for the Club Med Disco contest?” Yeah, yuck, yuck, yuck, for at least a solid week.

Which is why at this moment I could hardly believe my ears — or, gaping down at the pile of cash, my eyes.

“The Club Med Disco Contest?” I asked, amazed.

“Yep,” said Matt. “First place.”

I should say at this point that I’d never once seen my brother Matt dance, to any sort of music.

“I mean, what,” I said, absolutely gobsmacked. “Did you, like, move to the music?”

“Sam,” he said. “I was the music.”

A full account of his feat would fill this entire column. I might not have even believed Matt, had not a notable Hawaiian pro been in the audience, carrying on, right in the middle of the whole New Wave thing, a brave but illicit affair with a disco queen. And admittedly, he might have been more enthusiastic in recounting Matt’s performance, if it hadn’t meant 1) admitting that he’d actually attended a disco contest, and 2) that he only narrowly escaped getting punched up by a gang of drunken Afrikaners outside the club who wouldn’t abide a “colored” making out with a white girl. Nevertheless, this, apparently, is what went down inside Club Med that night

After lurking outside for a while, pretending to be a passerby, Matt quickly darted into the club. Laying down the R10 entry fee that we couldn’t afford, he settled in at the bar, where, to the throb of the four-on-the-floor drum beat, high-hat and syncopated bass line, he carefully nursed an orange juice we couldn’t afford, taking in the action out on the dance floor. There, under the giant hanging disco ball’s glittering rain, and to the cheering of the sizable crowd (fantastic promoters, the Club Med team), a series of garishly-costumed, obviously semi-professional couples effortlessly busted synchronized moves like The Hustle, The Bus Stop and the Get Down.

Matt George, circa 1981, showing he could surf as well as he could dance. Photo: Peter Broulliet

Did I tell you that this was a “partners competition?” Well, it was. Or was supposed to be.

After what seemed like hours (if he heard “I Feel Love” by Donna Summer, or “Disco Inferno” by the Trammps one more time he’d bust somebody’s move alright) Matt finally got the nod from the DJ. He walked over and whispered instructions, then moved out to the center of the now-darkened dance floor. And while the crowd at their tables and barstools buzzed and vibrated, there he stood in the dark, rhythmically tapping a booted toe. Long seconds passed, the tapping continued. Puzzled, the crowd started quieting down, then whispering among themselves. The tapping in the dark continued. The entire Club Med eventually grew silent. One second, two, three…then the DJ’s voice:

“Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome, all the way from California, Mr. Matthew!”

Matt stopped his tapping, commanded, “Hit It!,” and in the spotlight’s bright cone, began to dance to Lover Boy’s “The Kid Is Hot Tonight.”

“I don’t remember much of what happened after that,” he later admitted. “I was told that at one point I performed a backflip. All I do remember is that when I inadvertently ended my routine with what they called an “Electric Slide,” the whole place went crazy.”

Did I tell you that the Club Med Disco Contest was being judged by audience response? Well, it was. And thanks to Matt’s courageous, outrageous performance, we now had enough money to pay our bills and head off for more misadventure in Rio de Janeiro. But that, of course, is a story for another time.

Epilogue:

Later that year, a very creative, really funny guy named D. David Morin, editor at a short-lived, but culturally prescient, “action sport” publication called Action Now, put us on the cover of the September issue — an arresting image that featured Matt, smug in a white tux and carnation, with me dripping wet and in orange surf trunks, pointing at the camera and challenging: “Sure You Can Surf, But Can You Dance?”

Late-bloomers both, proving just how well we could surf would come later. But in 1981, thanks to Mr. Matthew, we sure as hell showed ‘em we could dance.