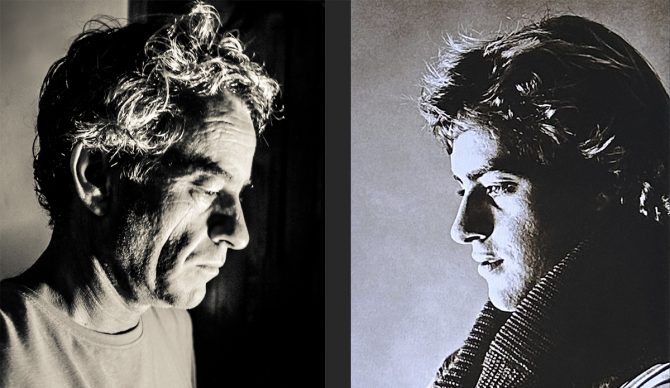

Tom and Tommy, 40 years on. Photos: Matt George, from his upcoming book Surfers I’ve Known

Editor’s Note: In this exclusive, three-part series, The Inertia’s Sam George looks past the standard profiles and promotion to capture the essence of what has made the great Tom Curren truly a legend in his own time.

The Oxford dictionary has a pretty broad sub-definition of a legend: “An extremely famous, or notorious person, especially in a particular field.” Hardly narrows it down much — modern surfing has plenty who qualify by this standard. Think Gabriel Medina (household name in Brazil), Carissa Moore (first Olympic champion) or the late Michael Peterson (as notorious as an Aussie can get), just to name a few.

Your average AI search does better, winnowing prospective candidates with a much more exceptional criteria: “A person becomes a legend by achieving something extraordinary, making a significant and lasting impact on their field or society, and inspiring others with their accomplishments, character, or unique way of thinking.”

This is our most exclusive club, and I’m putting surfers like Gerry Lopez, Laird Hamilton, Layne Beachley, Kelly Slater, Carissa Moore and the late Andy Irons in this column, all of whom having, throughout their illustrious careers, checked every box from the list above.

Then there’s Tom Curren.

This is where Oxford’s primary definition makes things interesting. Defining the term not as “a legend,” but rather “the legend,” describing the latter thusly: “a traditional story sometimes popularly regarded as historical but unauthenticated.” As in, “The legend of…”

The difference lies in the definitions. As extraordinarily accomplished are the legendary surfers cited above, there is, for example, no “Legend of Laird Hamilton”; no “Legend of Kelly Slater”…or of Andy Irons, for that matter. Simply because in every case, their talent— their individual brilliance — was made obvious virtually upon first introduction, their respective trajectories made piercingly clear; year after year, swell after swell, wave after wave, each fulfilled our every expectation. Of course, Laird was going to be the boldest, most innovative surfer of the modern era; of course, Carissa, so NSSA and WCT dominant, would someday win Olympic gold; of course, Kelly would become the greatest surfing competitor of all time; of course, Andy’s flame would burn too fiercely to burn long. Incredible contributions to surfing and surf culture; absolutely no surprises.

On the other hand, with Tom Curren the only unsurprising thing has been how, throughout the decades, he has consistently surprised us. So much so, that many of his more astounding achievements still demand authentication, as if even when photographic evidence exists, the stories surrounding him still need to be told, over and over again, for us to believe they actually happened. As when, for example, following his incredible 1990 WCT trials-to-title run, over the next three short years Curren gifted the surfing world with more astonishing exploits than would ordinarily be expected in a lifetime. Consider these few a primer on how “The Legends Of…” are born

1991, Miyazaki, Japan.

Visiting the Land Of The Rising Sun, Tom’s sponsored promo trip coincides with a gigantic typhoon swell, which lashes the coast with the largest, non-tsunami waves any of the locals had ever seen, totally mesmerized by a mysto, 20-foot outer-reef break, but even more so by sight of Tom Curren pulling his board out of a sponsor’s van, as if contemplating a solo go-out. Tom considers his conventional shortboard, then the raging lineup. Puts the board back in the van — good call. But then he walks across the street to a nearby surf shop, pulls out a handful of yen, and asks to see the biggest surfboard they’ve got. Walks back across the street with a thick, heavy, eight-foot pintail under his arm, bright red, with the logo “Willy Bird” on its deck. Suits up and paddles out alone. Inexplicably, right as he does the Quiksilver team van pulls up, and out hops Tommy Carroll and a young Kelly Slater. Spellbound, as if to verify that they’re actually seeing what they’re seeing, Kelly sets up a tripod and mans a camera, filming as Tom, all by himself in the chaotic lineup on “Willy Bird,” catches a handful of the biggest waves ever ridden in Japan. To this day the break, ridden only a handful of times since, is called “Curren’s Point.”

1991, Los Angeles, California

Initially intended as a fundraiser for the Surfrider Foundation, a pair of well-meaning music producers gather a number of prominent surfers, including world champions Rabbit Bartholomew, Frieda Zamba and Pam Burridge, in a downtown studio to record an album titled “Wave Sliders: In A Blue Room.” Essentially karaoke with AutoTune, all involved make a brave effort, with Rabbit’s version of the Steppenwolf classic “Born To Be Wild” certainly one of his most audacious performances, in or out of the water. Tom Curren, however, provides his own contribution to the collection. Working with a four-track recorder in his modest home studio, Curren records a cut titled “Whose Side Ya’ On,” on which he plays every instrument (guitar, bass, drums, keyboards), produces his own reverse tape effects and performs every vocal, including manipulating his taped voice to sound female and then singing harmony with himself. When played later to a record company executive, a friend is told that as a demo the song would earn a recording contract the next day. Tom decides to go surf empty French beach break instead.

(“In A Blue Room” is available on Amazon Music for $9.95. You almost owe it to yourself to take a listen.)

1991, Haleiwa, Hawaii

Now only half-heartedly committed to surfing’s pro tour, Tom, seeded in the Wyland Hawaiian Pro, stylishly carves his way to victory — his first-ever in Hawaii — knifing through good-sized Haleiwa on a sleek, Maurice Cole-shaped 7’3” blade, featuring the iconoclastic Aussie’s innovative “reverse-vee” bottom design. The board’s most notable feature, however, is the lack of sponsor’s stickers, on either bottom or deck. Purist’s everywhere delight, projecting that Curren is making an emphatic, anti-commercialization, “soul surfing” statement, deliberately choosing the North Shore’s infamous crucible of competition to do so. The truth is much more prosaic, and much more Curren. Apparently, his quiver of Coles, shipped from France, were misplaced by the airlines, and only arrived the day before the event. Having no sponsors stickers on hand, Tom chose to ride the 7’3” anyway, to obviously great competitive effect. Nevertheless, that longtime paycheck provider Ocean Pacific, perhaps aligned with soul surfers so far as reading Curren’s intent was concerned, summarily parted ways with Tom, only reinforced his reputation as surfing’s ultimate counter-culture hero.

1992, Seignosse, France

Growing increasingly disenchanted with surfing competition, as well as with conventional surfboard designs, Tom, who, when riding a number of self-shaped boards proves that he literally can ride anything, becomes interested in what today would euphemistically be called “alternative” boards. This includes a thick, wide, 5’11” transom-tailed Rick Surfboards shaped by Phil Becker during 1970s lamentable twin-fin trend, which he purchased from a New York surf shop. Riding it only once at home in France, Tom’s intrigued by its performance characteristics (which, to be honest, are mostly horrible), and confides that he might try using it in that season’s upcoming WCT event. To this end he enlists a friend to carry the brown, sun-faded toad of board down to the water’s edge under a towel, knowing that if the judging panel properly interpreted his intention, he’d never get through his opening round heat — or any other, if the ASP brass had their way. Carrying his conventional thruster down the beach in full sight of the crowd and judging tower, Tom whips off the towel and makes a last-second switch, paddling out to face opponent Matt Hoy on the terrible twin. The result is inevitable: watching Curren actually rip three-foot beach break peaks on the horrid board, Hoy becomes so flustered he can barely surf, and toward the end of the heat asks to give the twin a try (unsuccessfully, as it turns out, only enhancing Curren’s magic mojo) in what is certainly the most remarkable world tour heat ever surfed. “Why me?” laments Hoy afterward. Tom, for his part, has unmistakably stated his position on surf contests.

1993, Jeffreys Bay, South Africa

Virtually the entire surfing world considers it a crime that Tom Curren, Santa Barbara-raised and reared in Rincon’s right point splendor, has never surfed South Africa’s Jeffreys Bay, the right point against which all others are measured. A surfer-wave match made in heaven, so it is assumed. And so it turns out to be, when Tom finally makes his first trip down De Gama Road, steers into the parking lot overlooking J-Bay’s Supertubes section, pulls out a 6’6” Mark Rabbidge shape, makes his way over the rocks, paddles out, catches one quick warm-up wave, and then, on his second wave ever at the fabled point, drops in and…well, check out “The Best Ride In Surfing History” on The Inertia, published July 21, 2025.

Late entry “Honorable Mentions”: Curren’s 1994’s Fireball Fish” experimentation in pumping Bawa, on the Sumatran island of Nias (see: “The 10 Most Influential Surf Sessions Ever,” on The Inertia, February 5, 2025), and his 1995 North Shore Harry Houdini act, appearing out of nowhere to score the epic “Wave Of The Season” at Backdoor.

Tom Curren’s “unicorn” turn: the stuff of legend. Photo: Tom Servais.

But for all of these classic Curren moments, I’m taking it back to 1991, and an image snapped by renowned photographer Tom Servais on a beautiful Hawaiian afternoon at Backdoor Pipeline, to capture the essence of why Curren has and continues to float above a sea of talented peers in the eyes and imaginations of so many lifelong followers of the sport. In what is considered by many (at least many of those qualified to make the call) the greatest surfing action photo ever taken, the dynamism belies its purity. No logos on his person or board, the seamless marriage of power and grace, relaxed, expressive hands, a blend of both intense focus and purely instinctive movement; crystalized in this single moment is the enduring potency of Tom Curren’s mystique, and why there even exists “The Legend Of Tom Curren.” As I’ve written earlier in this series, Tom has been, and still is, the most unknowable of surf stars, just as intriguing (and often as bewildering) today as he’s ever been. And yet, to look at this single, remarkable moment in the man’s long, amazing ride, most of us, regardless of what sort of equipment we choose to ride, or for how long we’ve been riding it, or in what sorts of waves, find ourselves thinking that not only is this how we’d all like to surf, but is, in fact, is probably why we continue to do so. Simply searching for a brief moment of grace, like so many of those Tom Curren has given us throughout the years. As is befitting a surfer who’s become the true stuff of legend.

(Oh, yeah, he did this almost other-worldly turn after emerging from a long, stand-up barrel. You can see the full sequence here.)

Read part one of “The Legend of Tom Curren,” here, and part two, here.