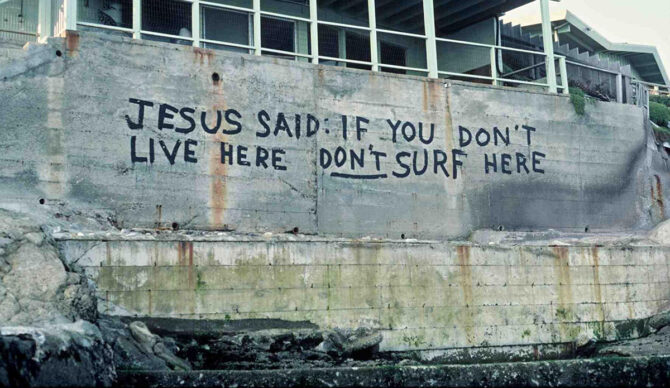

Is that message clear enough? Photo: Jeff Divine

I read an article the other day citing a 2023 YouGov poll that showed 41 percent of Americans believe that the Earth is only nine-and-a-half thousand years old, and that man and dinosaurs coexisted. I point to the results of this poll in the context having, at the same time, read many of the online comments posted in the wake of a recent viral video depicting an enraged Canary Islands “local,” first physically attacking, then hurling rocks at a visiting Venezuelan surfer. While a number of commenters decried the violent response, almost as many offered rationalizations, most often bemoaning the decline of the so-called “regulation” that aggressive localism once fostered in various lineups around the world, much, in their opinion, to the betterment of the sport.

Considering both these examples of group-think, I couldn’t help but wonder what brought these two subsets to their conclusions — especially those surfers. What has led an increasing number, at least judged by their online comments, to nostalgically harken back to a Golden Age of Localism, where lineups ruled by violent, street address-based hierarchies were somehow a better place? That maintaining the “soul” of surfing is somehow dependent on perceived “others” knowing their place, with the firm understanding that it’s most certainly not [insert surf spot here]? While I’ve written about localism before, in light of this newest viral incident I felt that a deeper dive into its history might be in order.

Before getting started, I’m making a clear distinction between Hawaiian surfing’s longstanding territorialism, and what I’ll later define as mere “localism.” Though the difference might not matter to the hapless haole visitor getting “slaps” from some skinny local at Rocky Point, territorial Hawaiian surfers at least have a historical, and, to my mind, noble precedent, their Island waves being just about the only place they retained any sort of sovereignty during the malignant cultural appropriation that took place in the late-19th, early-20th century at the hands of voracious Mainland business interests. Certainly not condoning any current actions, just acknowledging their origins.

That being said, so far as I can tell, the origins of what has come to be known as “localism” can be traced to Southern California in the mid-to-late-1950s. More specifically, Los Angeles’ South Bay. Despite the fact that only a relative handful of surfers prowled SoCal lineups at the time, hints of surfing’s nascent “us versus them” aesthetic can be traced as far back as 1956, and the classic novel The Ninth Wave, by renowned author (and political theory professor) Eugene Burdick. In one particular passage, his protagonist Mike Freesmith, a ruthlessly manipulative teenaged surfer (later to become an even more ruthless political figure) paddles out for a session at what reads like “Rat Beach” in Torrance:

“There were almost a dozen boys waiting on their boards. Some of them were lying flat on their backs, others were sitting with their feet dangling in the water. Mike saw that half of the boys were from Manual Arts High and the rest he did not know. He saw Hank Moore and paddled over to him.

“Hey Hank,” Mike called. “How’re they humping? Been waiting long for one?”

Deliberately ignoring unfamiliar surfers by demonstrably establishing pole position with use of a first-name “shout out”; 70 years ago, Professor Burdick appears to have written the very first lesson plan for a “Localism 101” class.

The late and legendary Greg Noll, hailing from Hermosa Beach, once told me, in reference to the massive wave of “wannabe” surfers who invaded his once untrammeled beaches following the release of the 1959 hit movie “Gidget”:

“There might’ve been 150 guys on the coast, and then came Gidget. And when the Valley guys started showing up, it was really bad. They were coming from, like, Cucamonga, which might as well have been Bangladesh. We didn’t even know there were places like that.”

“Can I interest you in a rock to the face?” Photo: Surfenspanol//Instagram

Enter the “Valley Guy,” the sport’s original “non-local” nemesis, referring to surfers driving over to the coast from the suburban sprawl of LA’s San Fernando Valley, yet embodying an archetype later to be derided at beaches around the world, describing anyone who lived “east of the Pacific Coast Highway,” at least figuratively. But it was on these SoCal beaches that the essential essence of localism was born. Which isn’t just to not want anyone else riding “your” waves, but to just as stridently not want anyone else to be living “your” life. Reflecting a purely assumed, rather than earned, form of elitism, defined by some arbitrarily established standard of intention. “Hey, I live closer to the beach than you do, so I obviously love the beach more than you do, and so naturally I deserve the waves more than you do.”

This was the corrosive aesthetic that spread north and south from the beaches of Los Angeles in the 1960s and throughout the 1970s. San Diego’s La Jolla and Point Loma, Lunada Bay in Palo Verdes, Ventura’s Hollywood-by-the-Sea, the coastline west of Rincon (mention the Hollister Ranch at your peril!): these were some of the spots where aggressive resistance to fellow surfers became the norm, providing a template that would be adopted at jealously guarded breaks in every latitude.

One of the earliest, and most graphic, depictions of localism with a capital “L” came in a 1972 issue of SURFING magazine, when a team of Windansea surfers, including Mike Purpus, Gary Goodrum and Gary Keating, along with photographer Dan Merkel, was dispatched to a notoriously hostile point break in Seaside, Oregon. Titled “Oregon: Love It Or Leave It,” Seaside locals made it abundantly clear which option they preferred these Down South outlanders choose, “courageously” defending their wave with plenty of bad vibes and a couple of flat tires. The first full magazine feature to address localism (a 1969 issue of SURFER featured a short sidebar called “Haole Go Home,” penned by an anonymous North Shore local, but like I said, that doesn’t count here), the accompanying photo of a prominent surf star like Mike Purpus re-inflating his car tire with a bike pump troubled many surfers, I’m sure, but obviously inspired many others; aggressive, often violent localism became one of surfing’s most potent trends throughout the 1970s.

And often the most ridiculous. I can recall an incident in 1977, when, having moved to California’s Central Coast three years previously, I accosted a Morro Bay “local,” who, caught in the early stages of applying Sex Wax to the windshield of my Datsun pickup, settled for snarling “LA go home!”

“I moved here from up by San Francisco,” I reminded him. “Where I’m from, you’re LA.”

“Hey, man,” he said, his snarl flattening into a whine. “Don’t ever say that, man”

“Anyway,” I said. “What makes you think I’m from LA?”

“You and your brother and your friends,” he complained. “Always talking out in the water and having fun all the time.”

This was the Golden Era of Localism in a nutshell, with fellow surfers being condemned, reviled, even, for the simple crime of having fun in a surfing environment where having fun had long ago been replaced by a dogged determination to make sure surfing was no fun at all — for neither the “local” nor the interloper. Testimony to this warped ethic being the establishment, over these many years, of a rogue’s catalog of some of the least-fun surf spots on earth: notorious West Coast epicenters of anger, aggro South and Western Australian “secret spots,” frigid Canadian point breaks, the Indian Ocean’s supposedly peaceful “Island of Santosha” (Namaste? More like “Namaste out of our waves, mon invité indésirable!), and now, judging by the very latest TikTok clip, Tenerife’s Punta Blanca. Because I ask you, does that rock-throwing Tenerife local, or, in fact, any of the other angry, outraged, often violent protectors of their precious surf spots you may have encountered throughout the decades, appear to be having fun? After flattening Purpus’ tires, waxing my windshield, or, all these years later, throwing rocks at the courteous Venezuelan, did any of these “locals” then paddle back out and have a great time surfing?

If you think so; if you think any of this systemic ass-holiness should be justified, lamenting the end of the Golden Era of Localism, because before everybody got lawyers and cell phones it meant that while some other unlucky guy or gal was getting screamed at, or slapped around, or beat down by self-righteous “regulators,” you, keeping your head down, no doubt, took advantage of the opportunity to scrounge a few extra waves; if you think surfing was somehow better back then, praising localism’s abhorrent contribution to modern surf culture, then I say that compared to the 41 percent of Americans who believe that “The Flintstones” was an animated documentary, you’re the idiot. I tend to give a pass to those who believe that “The Flintstones” was an animated documentary. At least their indefensible stance is rooted in faith.