In Swahili, the word Uhuru means “freedom.” It’s the name of Mount Kilimanjaro’s highest peak. Known as the Roof of Africa, it touches the clouds at nearly 20,000 feet. It’s not a particularly technical climb, but as the African jewel in the Seven Summits crown, it’s the highest free-standing mountain on the planet. It’s not an easy thing to do, though, and it’s a lot more difficult when you’re carting a mountain bike on your back. Daniel Cristancho, a non-professional rider and mountain bike guide, decided that he’d like to ride down it… but the only way up is up.

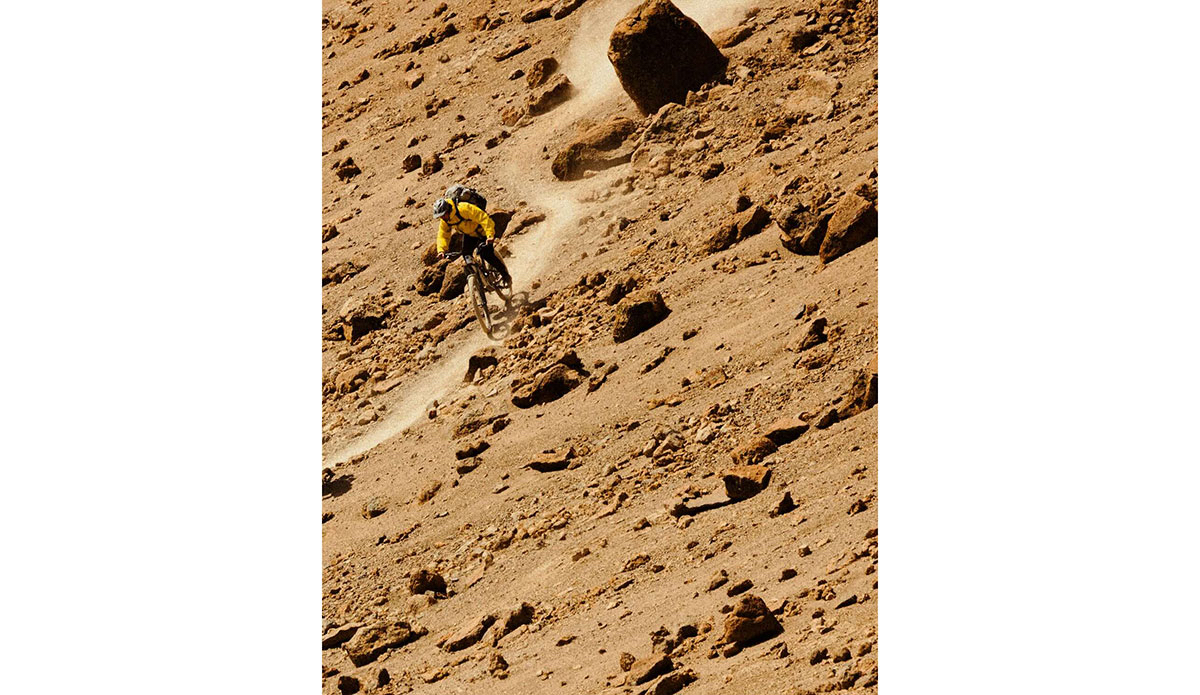

Climbing Kilimanjaro requires one to hike through five different climate zones. The lower slopes — once mostly rolling savannas, are now used for small scale farming and grazing. As you move up, you enter a warm and humid rain forest before hitting an alpine desert that spans from about 13,000 feet to 16,400 feet. You’re past the lush greenery and into bleak terrain that bakes like an oven during the day and plummets in temperature overnight. It almost never rains here, so the landscape is barren and rocky. When you’ve hiked through that, you enter an arctic tundra that continues until the very top at 19,340 feet. The ground underfoot is made up of volcanic scree, and glaciers loom above you. It’s a tough thing to prepare for, especially if you are unlucky enough to get altitude sickness, which is common.

Cristancho, a 22-year-old who was born in Columbia and raised in Catalonia’s Val d’Aran, is an up-and-coming mountain biker. He competes mostly in downhill and enduro, and he combines his racing career with work as a guide and instructor.

“You start out in the jungle wearing a t-shirt and end up in snow at the summit, with a down jacket and balaclava,” Cristancho said. “We were all short of breath, every step became a lesson in humility: advancing just 20 centimeters per step, at two kilometers an hour. But when we reached the summit, the emotion made us cry.”

The trip really started on Christmas day, when Cristancho got a phone call from his filmmaker friend Carlos Farrera. Carlos told Daniel that they, along with fellow mountain bike guide Dani Bosque and filmmaker and friend Jaime Varela, had pulled the trigger on the adventure. They wanted to make a film about it, which they called Uhuru. To make the film, they would need to carry an enormous amount of gear with them. Nearly 50 pounds of camera gear — drones, stabilizers, cameras, batteries and even a small generator — as well as tents and food. A team of porters helped them, but Daniel didn’t let go of his bike.

After four days of climbing, Cristancho and his team finally reached the summit of Uhuru. Although the climb was part of the journey, the ride down was what they really came for.

“The descent — the long-awaited moment — was as spectacular as it was brutal,” an email from Cristancho’s team reads. “From the snowy volcanic landscapes at the top to the humid jungle with roots and monkeys as soundtrack, it was a 26-kilometer (16 mile) ride, almost entirely cyclable. A day and a half of filming to capture Dani’s dream images for posterity, and to see giraffes, lions, flamingos, and elephants on the way out of the National Park.”

The film they ended up with is spectacular. Created for Blue Banana‘s One Shot, an annual series capturing spectacular images of nature with top photographers and filmmakers, it’s well worth the watch for anyone who loves a good adventure.